An ancient temple hidden right under archaeologists’ noses at Tikal, one of the world’s most famous Maya sites, hints at a tantalizing connection between the Guatemalan city and Teotihuacan, a Mesoamerican civilization near modern-day Mexico City, more than 800 miles away.

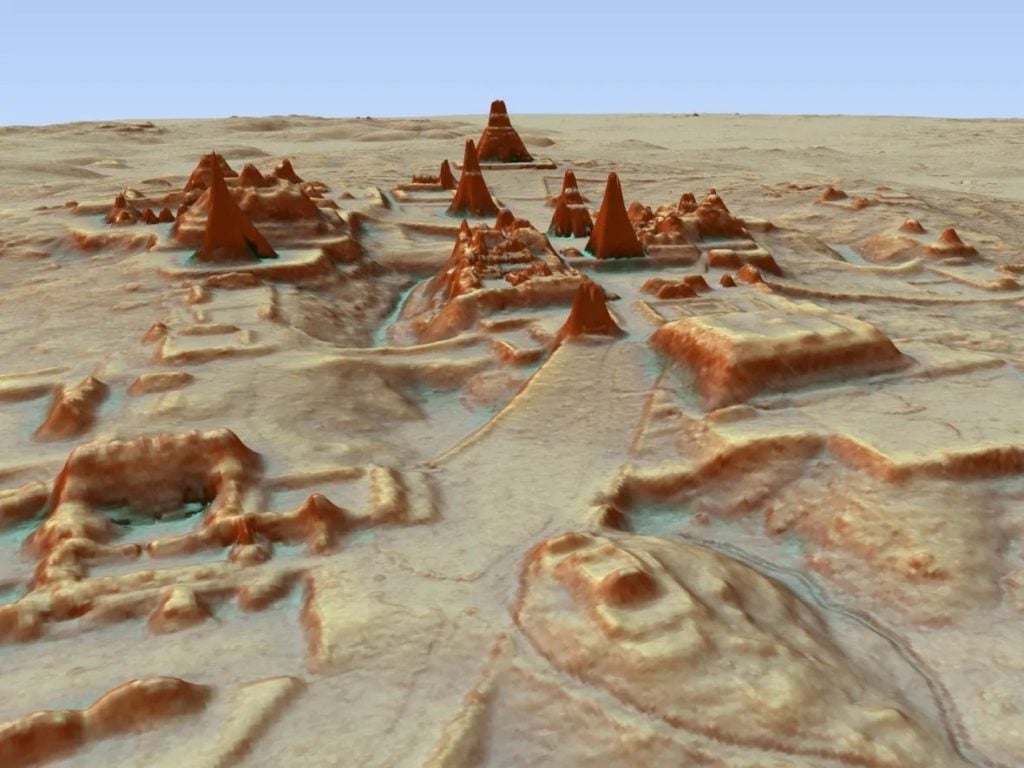

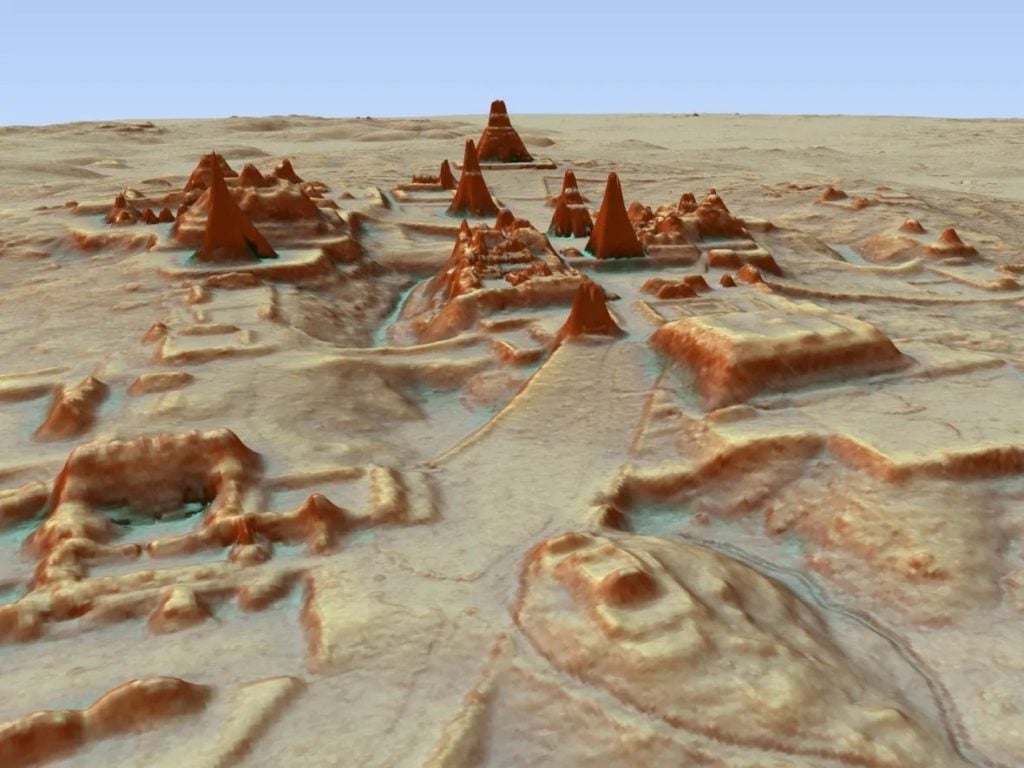

Thanks to an aerial image created via Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), archaeologists now know that an unassuming hill in the Tikal landscape is actually a buried pyramid hidden beneath layers of dirt and plants.

And the lost structure doesn’t look like the ancient city’s surviving buildings. Instead, it has all the trademarks of a Teotihuacan pyramid, resembling a half-size replica of the courtyard there that the Spanish dubbed the “Citadel” for its fort-like appearance.

Subsequent excavations by the South Tikal Archaeological Project found that the site has many apparent ties to early fourth-century Teotihuacan, from construction and burial practices, to the types of ceramics and weaponry found inside, including darts made from green obsidian from central Mexico. There was even an artifact decorated with the Teotihuacan rain god.

One of the pyramids in the Citadel, talud-tablero pyramidal structure, at Teotihuacan (Unesco World Heritage List, 1987) in Anahuac, Mexico. Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images.

The find is significant both because the buried building is such a major monument and because it suggests that Tikal could have been an outpost of the Teotihuacan empire.

“We knew that the Teotihuacanos had at least some presence and influence in Tikal and nearby Maya areas prior to the year 378,” Edwin Román-Ramírez, director of the South Tikal Archaeological Project, told National Geographic. “But it wasn’t clear whether the Maya were just emulating aspects of the region’s most powerful kingdom. Now there’s evidence that the relationship was much more than that.”

The discovery is the latest made by the LiDAR initiative from Patrimonio Cultural y Natural Maya (PACUNAM), Guatemala’s Maya heritage foundation.

Panorama of the Great Plaza in the ruins of the Mayan civilization in Tikal National Park, Guatemala. Photo by Getty Images.

LiDAR uses laser pulses and a GPS system to take topographical readings of the earth’s surface and generate three-dimensional maps. The maps can reveal man-made structures that have become overgrown over the centuries, especially low-lying linear ones, such as roads or irrigation systems that might blend into the landscape even at close range.

The technology is particularly useful in areas of dense jungles, where surveying the area on foot can take decades. In 2018, PACUNAM revealed that the Maya lowlands were home to thousands of unknown ancient structures, all discovered in one fell swoop back in 2018 thanks to LiDAR.

The find instantly transformed archaeologists’ understanding of the region, which was almost certainly populated by millions more people than previously thought.

A LiDAR scan of the ancient Maya city of Tikal. Image courtesy of Marcello Canuto/PACUNAM.

PACUNAM isn’t sure if the people who built the newly discovered temple at Tikal were from Teotihuacan, but they were certainly familiar with the kingdom’s culture and traditions, and practiced the same religion. An isotopic analysis of a skeleton buried on the site may be able to tell archaeologists where the deceased lived, and if they came to Tikal from Central Mexico.

Preliminary dating suggests that construction on the Teotihuacan-style temple began prior to 278. That was 100 years before Teotihuacan sent his son to conquer Tikal, an event recounted in Maya inscriptions.

Around the same time, a neighborhood in Teotihuacan decorated in the Maya style was destroyed and elaborate Maya murals were smashed and buried, suggesting a breakdown in the alliance between the two peoples. Archaeologists hope further excavations will help provide a better understand of this history.