Up Next

Tina Braegger on Why She Has Been Painting Only ‘Grateful Dead’ Bears for More Than a Decade

The Swiss artist, who has painted more than 150 bears, recently published a surrealist novel.

The Swiss artist, who has painted more than 150 bears, recently published a surrealist novel.

Kate Brown

The Grateful Dead bear, the one that’s usually found dancing across tie-dye T-shirts, bucket hats, and the bumpers of cars, is a core symbol of free-wheeling, acid-laced 1970s spirit. The unofficial logo first appeared on the back of the eponymous rock band’s vinyl, an inside joke about the group’s sound engineer “Bear” Stanley, who dolled out a lot of LSD and had a unique way of dancing at concerts.

The Swiss artist Tina Braegger, who paints Grateful Dead bears, is not moved by those history references. Much more interesting to her is what happens when you take that context away. She’s curious about the widening chasm between a copy and its original, what happens to a symbol as ubiquitous as the dancing bear when it gets serially reused. In this pursuit to tease out the bear’s ambiguity, its signature cartoonish mane-like collar and enigmatic expression have appeared on more than 150 of Braegger’s paintings—every single one of them.

And while she’s come to know it well—the bear is her one and only subject—the character remains beyond reach. The image has never really become hers. She shrugs about it: “It’s an open-source thing,” she says while we sit together in her studio in Berlin. She keeps a distance from her muse and to the notion of painting as well. “I avoid labeling myself as a painter,” she adds. “If someone says ‘I hate those bears,’ it doesn’t really hurt me, because it’s not my thing. I can come along and look at the artwork with them and say, ‘I hate them too.”

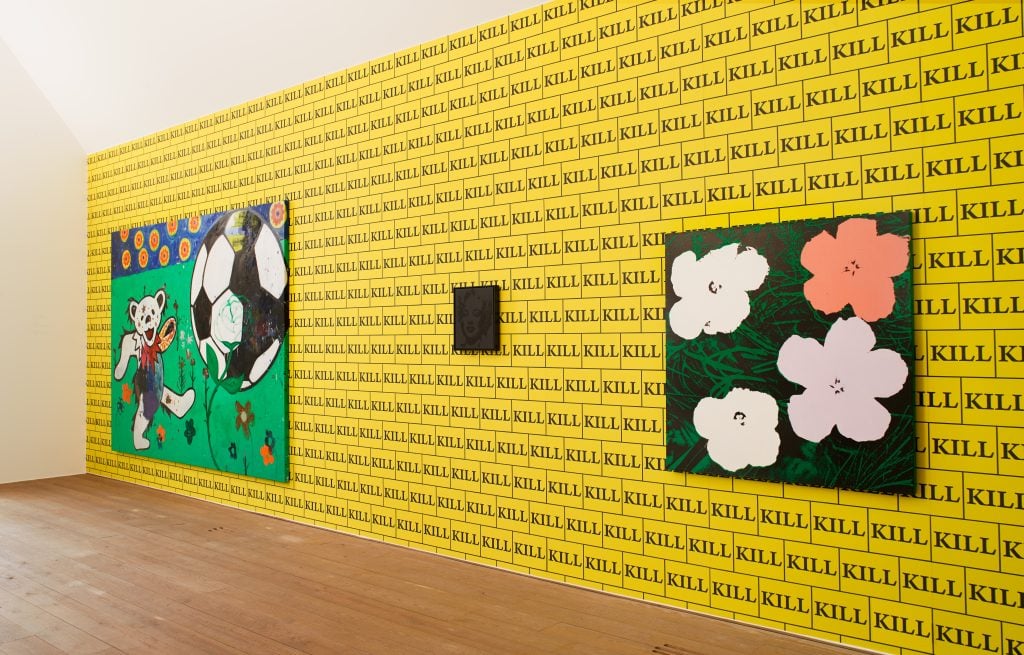

Installation view, “Ich werde hier sein im Sonnenschein und im Schatten”, Société, Berlin, 2020.

Braegger’s bears, which she first committed herself to in 2011, are ever-transforming. In one painting, there is a bear in blue washes of oil paint; in another, a bear dances on a chair and on one canvas it dances within a chaotic cosmos of suns. Another painted bear appears warped like a Photoshop tool was dragged it across its face. If you stand among her paintings in a gallery, it becomes a fun house of mirrors, wherein each reflected bear is somehow different but the same. No matter the form, its always smiling out, empty eyes, a mouth a bit too agape.

There is a slippage, she says, where a motif tumbles through contexts online, and it fascinates Braegger. The Grateful dead bear has fallen away from its roots in psych rock, fallen off the backs of vinyls and onto the t-shirts of Travis Scott, onto H&M racks, but also U.K. high fashion labels like J.W. Anderson. “It is devoid of meaning in a sense,” Braegger notes. “It comes from a subculture and so there was a certain political and ethical background to it, but it is not bound to any moral standard. It could well be Trump’s next election logo.” That would be not unlike the story of Pepe the Frog, an innocent cartoon character that became a ubiquitious meme for right-wing trolls. There is also the mouth and tongue of Indian goddess Kali, which became practically synonymous with the logo of the Rolling Stones, and now, to a post-Stones generation, it is just another anonymous logo on a BIC lighter.

“The holy beast is watching us”, Weiertal Biennale, Winterthur, 2019.

“There is a disconnect between the psychedelic marching bear and the name ‘grateful dead,’ when you take them out of context,” she says. To further destabilize them, her children occasionally contribute to her paintings. “I like to be able to do something where someone may come to the gallery and say ‘my kid could have done this better’ and where I can answer ‘well, my kid actually did that.’ [I’m] questioning an elitist approach, but then also reinforcing it, as it’s not the work of someone else’s child, but mine.”

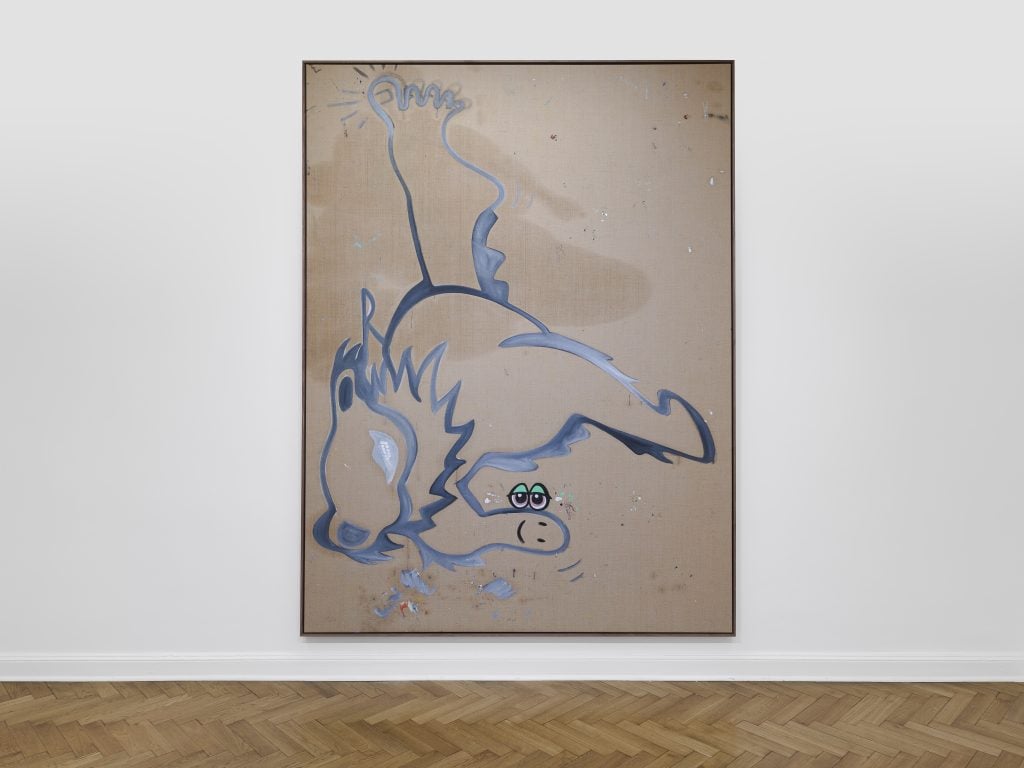

Throughout the work are references to art history that offer clues to what her cues may be. There is a bear within a bloom of Warholian flowers; there is upside down bear recalling the male painter star Georg Baselitz that may point to the kinds of canons she is questioning, namely, the idea of the painter as a single ingenious author. Udo Kittelman curated a show with Braegger’s work in 2021 that placed the bears in the pictorial universe of Sturtevant. Braegger remembers seeing the artist’s work when she was at a museum with her mother when she was young. “Encountering Sturtevant’s work was the first time I really saw that everything is possible in art,” she said. “The copy, the original, the value system of behind them.”

Installation view, “Curiosity Killed the Cat”, de 11 Lijnen, Oudenburg, 2021. Tina Braegger and Sturtevant, curated by Udo Kittelmann.

Braegger wrote a fictional novel about the bear’s origin story called The Grateful Dead: a Diary by Gabriel Krampus (2019). Krampus, like the bear perhaps, can in moments appear to be a self-portrait of Braegger. The psychological strangeness has been distilled into another surrealist novel she published at the end of last year, called The Dream Relatives. A book launch is soon planned for New York.

In the new story, a woman artist, who also paints bears, gets drawn in by the secret service to help scam nations into believing that artificial intelligence really exists when it is just the main character writing all the content for the entire world. There is an interesting connection between A.I. and Braegger’s bears—both conjure questions about reproduction, appropriation, creativity, and automation.

Installation view, “Ich bin hier raus, holt mich ein Star”, Société, Berlin, 2023. Photo Trevor Good.

Currently, she is working on a catalogue raisonné that will chronicle the bear through its many transformations, up to its recent manifestations, where it appears to more deconstructed than it has ever been. In her recent exhibition at Berlin gallery Société, called “Ich bin hier raus, holt mich ein Star” (“I’m out of here, get me a star”), things are shifting again. Three bears appear in a room that could be a gallery. “I needed to go the painful way of painting more than 150 bears to be able to allow myself to paint them in three dimensional space,” she says of that work. “I need to now stretch the bear to its limits.” One is caught in a painting within the painting, another is splayed across the floor, and one is heading out a door. Could it be foreshadowing of a total exit?

There are other signs the bear might disappear, or at least become more deconstructed. By separating it into distinct parts, the dancing bear becomes more sinister. In Sarvangasana (2023), which was also on view at Société, the figure is only an outline and its eyes sit outside of its head held in its paw. In a smaller work on canvas, A spin in the laundromat (2023), the bear has a huge eye where its head should be, except that the eye also looks like a saw blade positioned to bisect the body.

Wherever this trip is headed, making something familiar strange and debasing the power games inherent to painting as well as art-making, or authorship more generally, is what I find enticing about Braegger’s practice. “There is something very elitist about art, which is fine,” she tells me. “I am not necessarily questioning that. I am interested in doing something that does not only speak to art people, but to dead heads and everybody else.”

More Trending Stories:

A Case for Enjoying ‘The Curse,’ Showtime’s Absurdist Take on Art and Media

Artist Ryan Trecartin Built His Career on the Internet. Now, He’s Decided It’s Pretty Boring

I Make Art With A.I. Here’s Why All Artists Need to Stop Worrying and Embrace the Technology

Sotheby’s Exec Paints an Ugly Picture of Yves Bouvier’s Deceptions in Ongoing Rybolovlev Trial

Loie Hollowell’s New Move From Abstraction to Realism Is Not a One-Way Journey