On View

A Haunting Virtuoso of the Renaissance, Tintoretto’s Personal Side Has Remained a Mystery. Now the Met Wants to Change That

On his 500th birthday, museums across the world are reexamining Tintoretto's still-underappreciated greatness.

On his 500th birthday, museums across the world are reexamining Tintoretto's still-underappreciated greatness.

Sarah Cascone

This fall marks the 500th anniversary of the birth of the great Italian Renaissance painter Jacobo Tintoretto—but despite his undeniable Old Master pedigree, the artist falls short of household name status here in the States.

Luckily, there are a few shows in the US that should go a ways toward rectifying the situation, including “Celebrating Tintoretto: Portrait Paintings and Studio Drawings,” which opened last month at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

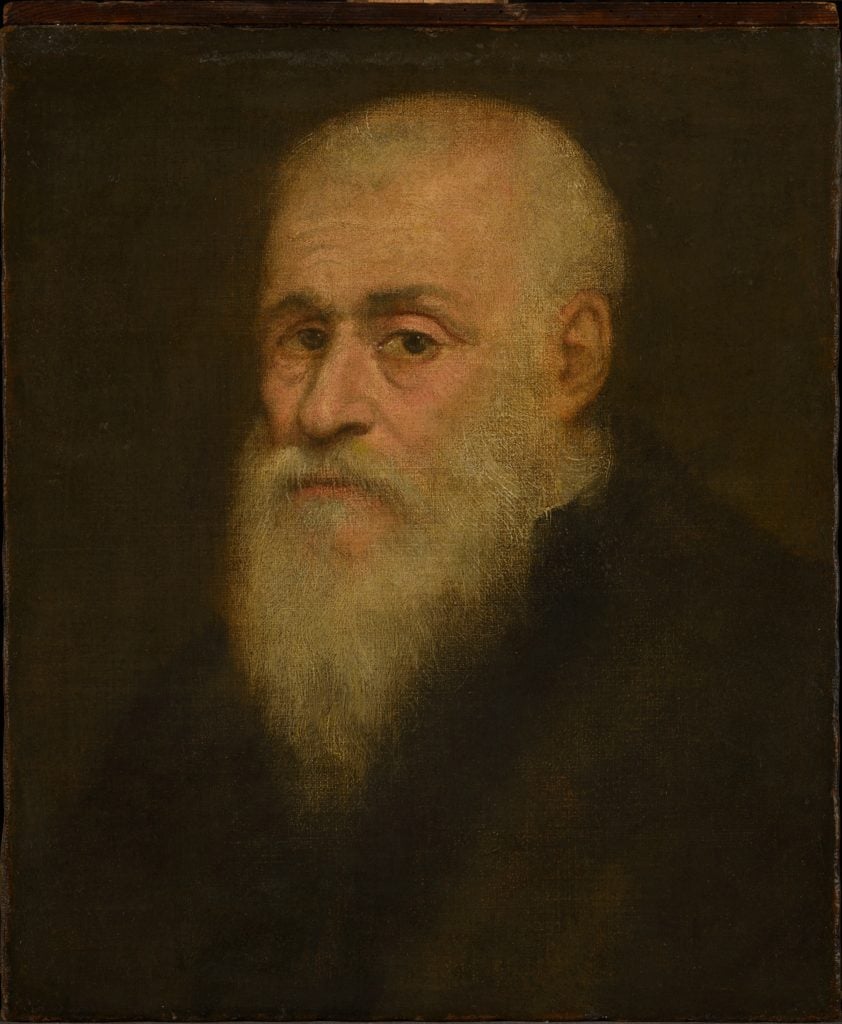

Jacopo Tintoretto, Portrait of a Man (Self-Portrait) (1550s). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The explanation for Tintoretto’s relative obscurity is simple. A Venetian through and through, the artist rarely left his home city, and a large percentage of his works remain there to this day. “Starting out, he had to work alongside Titian, who had an international career,” Andrea Bayer, the Met’s deputy director for collections and administration, told artnet News. “Tintoretto, probably being a pragmatic businessman, decided to focus on a more local clientele.”

That included working for wealthy patricians, painting portraits to hang in their palaces, as well as commissions for churches and civic buildings. As a result, comparatively few of his works have crossed the Atlantic to this day, although “all American museums have tried to buy his work,” said Bayer. “He is one of the three great painters of the Venetian Renaissance.”

“We knew that we wanted to celebrate Tintoretto in some way during his birthday year,” Bayer added. “Because his achievements in large narrative paintings and elaborate multi-figure compositions would be covered [at other institutions in] more monographic shows in which his entire oeuvre would be studied, we wanted to focus on something less well-known.”

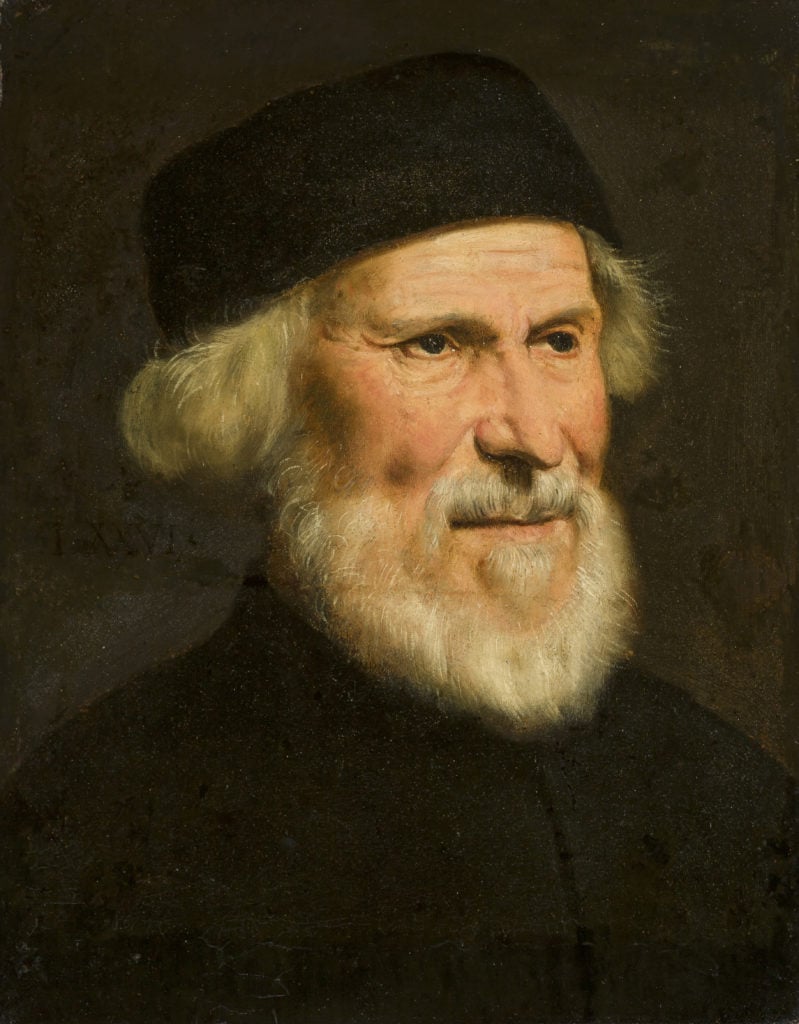

Jacopo Tintoretto, Head of an Old Man (1555–65). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Met has four Tintoretto paintings, plus a selection of his drawings, which were the logical starting point for their exhibition. “Both the portraits and the drawings are of a startling modernity,” said Bayer. “We felt quite sure that when people got to know these other sides of his practice, they would see him through a different lens.”

The centerpiece is Portrait of a Man, which inspired Bayer and Alison Manges Nogueira, an associate curator in the museum’s Robert Lehman Collection, to focus on the artist’s portrait studies. Unlike typical Renaissance portraits, meant to convey status and allow the subject to be remembered for posterity, these smaller, more personal works are informal.

“Sometimes Tintoretto included absolutely fantastic portraits within the narrative canvases that are very probing and penetrating, but often the faces have that distant, commemorative feeling in his larger compositions,” said Bayer. In comparison, his portrait studies “seem to be moments where he could come close to individuals and express something about their character and their personality.”

Tintoretto, Portrait of a Venetian (circa 1550). Courtesy of the San Diego Museum of Art.

“Tintoretto seems to have done these throughout his career,” Bayer added, noting that it isn’t clear who all the sitters were, or if Tintoretto was commissioned to create the portraits, gave them as gifts, or kept them in his studio.

The museum learned more about the works, some of which are international loans, through x-rays, which allow art historians to “see how swiftly and surely the whole thing is laid in,” Bayer explained. “Tintoretto’s definitely painting with the sitter right there. You have the sense of the artist laying in the underlying lead white drawing that he’s using to create forms.”

“Tintoretto worked quickly and seemingly spontaneously to achieve great dramatic coloristic effect,” she explained. “When you go to see his works around Venice, you are very struck by the rapidity by which he seems have been able paint, and his use of light and dark to convey movement.”

Domenico Tintoretto, Reclining Female Nude (early 17th century). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

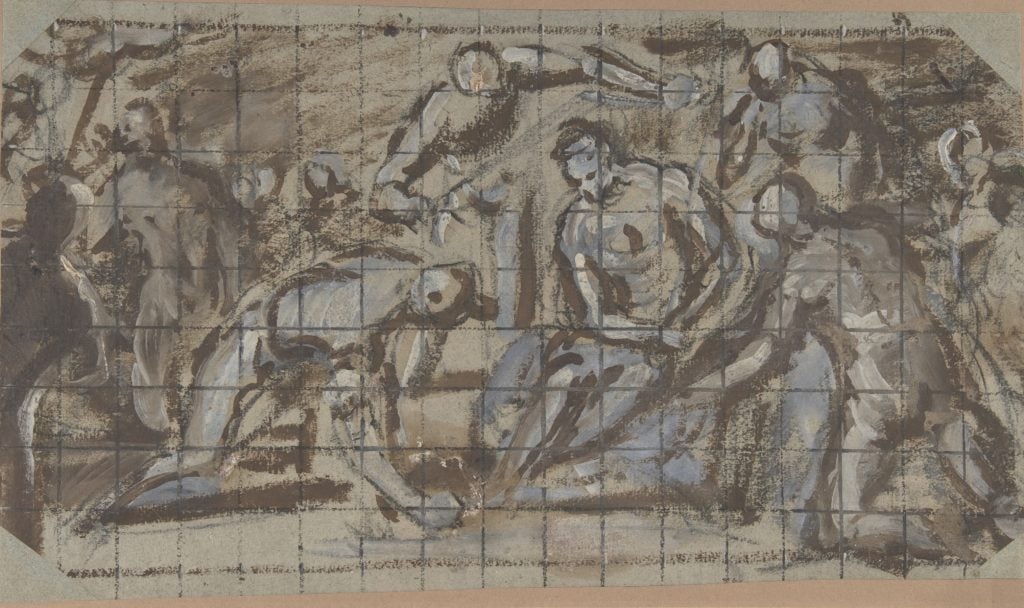

A second part of the Met exhibition focuses on the Lehmann collection’s Tintoretto drawings, including works by the artist’s son, Domenico Tintoretto.

“Because Domenico was the pupil of his father and his primary collaborator, their styles are quite similar,” Manges Nogueira told artnet News. “But one thing that set him apart from his father was his drawings of female nudes. These drawings show that Domenico was interested in more naturalistic modeling. There’s an incredible attention to depicting the female form, in a very beautiful idealized way, but also in a very stark and unidealized way that was very unusual for this time.”

Of particular note is an oil on paper drawing, painted with a brush by Domenico as a compositional study. “None have survived from Jacobo, so it’s an extremely important document that tells us much about artistic practice and the way that drawing functioned in the Tintoretto workshop,” Manges Nogueira explained. “It blurs the boundary between drawing and painting.”

Domenico Tintoretto, The Mocking of Christ. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Met’s Tintoretto show is one of many marking the artist’s 500th birthday. Colonge’s Wakkraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud kicked things off last fall with “Tintoretto: A Star is Born,” and the Paris Musée du Luxembourg followed suit this March with “Tintoretto: Birth of a Genius.” New York’s Morgan Library and Museum is doing “Drawing in Tintoretto’s Venice,” which also opened last month and is on view through January 6.

And of course, there is Venice, where “The Young Tintoretto” at the Gallerie dell’Accademia and “Tintoretto: 1519–1594” at the Palazzo Ducale opened in September—the later will head to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, thanks in part to US conservation charity Save Venice. Titled “Tintoretto: Artist of Renaissance Venice,” the show will be the artist’s first retrospective in the US.

“Many people of course know Tintoretto and have gone to Venice and seen his great works. But having said that, his name is not a Renaissance name that comes easily to the tip of people’s tongues,” Bayer admitted. She hopes the Met’s exhibition, paired with the Morgan and NGA shows, will provide an “introduction for American viewers that will put him more firmly at the center of their understanding of the Italian Renaissance.”

“Celebrating Tintoretto: Portrait Paintings and Studio Drawings” is on view at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York, October 16, 2018–January 27, 2019.