Art World

10 Treasures of the Metropolitan Museum to Broaden Your Mind and Lift Your Spirits

Here is art to give thanks for.

Here is art to give thanks for.

Ben Davis

Encyclopedic museums like the Metropolitan Museum are certainly not innocent of struggles over power and plunder and control of the cultural narrative. But it’s been an exhausting season of struggle, with more on the horizon, in the wake of the US presidential election. So, as the Thanksgiving holidays came on, I passed through the Met galleries, looking for a few of items that gave me a sense of perspective.

Here’s my tour of 10 items that offer something to connect to right now, and also remind me of how tiny and limited my own experience is, and how much more there is to know.

Human-headed winged lion and human-headed bull (lamassu). Image: Ben Davis.

Human-headed winged lion / Human-headed winged bull, ca. 883–859 BC

The Neo-Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) is known for the unrelenting ruthlessness of his conquests, sometimes flaying his critics alive. He was also known for christening his magnificent capital city with a 10-day feast that welcomed 69,000 people, still remembered as one of history’s great parties. This stately pair of “Lamassu”—one a man-headed lion, the other a man-headed bull—decorated a gate in the city, and are correspondingly both fearsome and sophisticated, a reminder that the two qualities can easily fit together. Ashurnasirpal II’s capital today is Nimrud, in Northern Iraq; it was retaken days ago by Iraqi forces in the war against ISIS.

Pair of Seated Figures Playing Liubo. Image: Ben Davis.

Pair of Seated Figures Playing Liubo / Luibo Board and Pieces, 1st century BC–1st century AD

Earthenware funerary figures depicting a wish for afterlife contentment that is utterly charming in its small-scale everydayness: two gentleman, deep in thought, entertaining one another over a board game. (Liubo was a popular gambling game during China’s Han dynasty.)

Dancing Celestial Deity (Devata), mid-11th century. Image: Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Dancing Celestial Deity (Devata), mid-11th century

Bent into a sandstone pirouette, the figure, originally from a temple in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, represents a Hindu demigoddess captured in the throes of devotional dance. Her anatomically impossible pose, to me, makes the figure amazingly vital, while also suggesting divine superpowers. It’s by far one of the most vivid and gorgeous statues in the collection.

Seated Figure, 13th century. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Seated Figure, 13th century

It’s not clear, I gather, whether this figure is cradling his head in pain or in prayer, or whether the rows of lumps on its back represent scars, or ornament, or some kind of disease. The Met’s Seated Figure was excavated at Djenné-Jeno, in what is today Mali, during a time when that city had already begun its decline. By 1400, it was abandoned. No one knows why. Maybe this figure’s enigmatic grimace holds a clue.

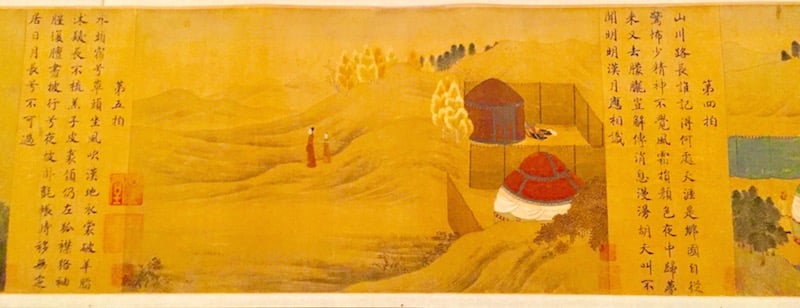

Unidentified artist (after Song dynasty painter), Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute; The Story of Lady Wenji, Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), early 15th century. Image: Ben Davis.

Unidentified artist (after Song dynasty painter), Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute; The Story of Lady Wenji, early 15th century (Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644)

The multi-part scroll is a true weepy, recounting Han Dynasty poet Lady Wenji’s tale of being abducted by Mongol raiders, bearing children, and then having to abandon them to return to her family. The actual historical incident dates from 195 AD; this scroll, from 12 centuries later, when Wenji’s odyssey became a metaphor for the emperor of the Southern Song Dynasty’s own separation from his family in the struggle for control of China.

The leaf of the scroll featuring Lady Wenji’s tiny figure with her attendant standing isolated in the middle of a forsaken steppe, lamenting her fate, is indelible.

Queen Mother Pendant Mask. Image: Ben Davis.

Queen Mother Pendant Mask: Iyoba, 16th century

In the 1500s, strife engulfed the Kingdom of Benin. Idia, the mother of the oba (king), was so highly regarded for her military council and role in passing through the tumult, that he would create a new title and position at court for her: “iyoba” (i.e. Queen Mother). The ivory mask, which belonged to oba Esigie, was meant to commemorate Idia’s likeness, and those twin metal bars inset between her eyes supposedly represent “the medicine-filled incisions that were one source of Idia’s metaphysical power.”

Unknown Artist, Crown of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, ca. 1660–1770. Image courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Crown of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, known as the Crown of the Andes, ca. 1660

So much beauty; such a wild backstory.

The gold repoussé “Crown of the Andes” is studded with some 250 emeralds, including the “Atahualpa emerald,” thought to be pilfered from the Inca ruler Atahualpa in 1532. Considered one of the greatest feats of Colonial gold work, the crown was originally created by pious Catholics of the colonial city of Popayán, in Colombia, to adorn a devotional statue of the Virgin Mary after she was thought to have interceded to halt a smallpox epidemic.

In the 20th century, Popayán’s cathedral sold the treasure to endow social services. A consortium of US gem dealers bought it, with the intention to strip it for parts. They found, however, that public interest in the treasure was its own money-maker: During the Great Depression, General Motors put it on display in Detroit, and the trophy that had once attracted the faithful to honor the Virgin drew 225,000 visitors in a week to promote the new Chevrolet line of cars. Now the Crown of the Andes sits in the museum, purchased last year as “an anchor for the development of a new area of collection at the Met.”

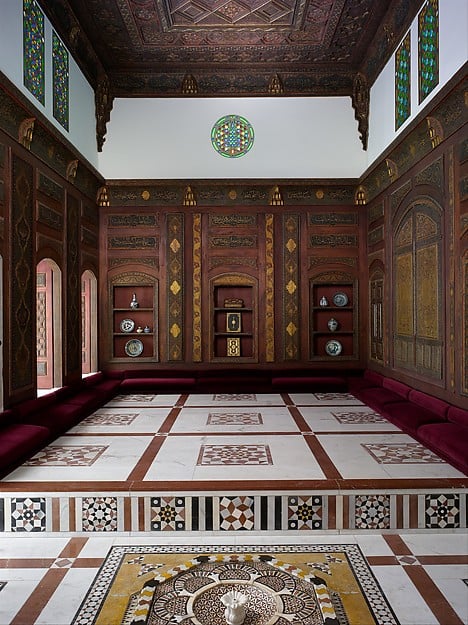

The Damascus Room at the Met. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Damascus Room, dated 1119 AH/1707 AD

A crisp transplant of an entire “winter reception chamber” (qa’a) from Syria, Damascus Room, the Met boasts, is one of “the earliest extant, nearly complete interiors of its kind,” a showpiece of late Ottoman refinement, complete with babbling fountain in its tiled antechamber.

The wealthy Damascene family who once lived here literally lived among poetry, the panels of this salon intricately inlaid with verses such as the following: “O you who were chosen before Adam sprouted, before the locks of existence were opened / Can a creature desire to praise you, after that Creator has praised your qualities?”

Kay Sage, Tomorrow Is Never, 1955. Image: Ben Davis.

Kay Sage, Tomorrow Is Never, 1955

An indeterminate landscape of mist, punctuated by shrouded statues clad in scaffolding, painted in that strange, over-lucid Surrealist style. Sage was from the US, but met her husband, creative interlocutor, and fellow Surrealist Yves Tanguy, in France. They fled World War II to Connecticut, where they painted side-by-side for many years. This painting, the Met tells us, was the first Sage painted after Tanguy died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage, lending an extra dash of pathos to its vision of a desolated world.

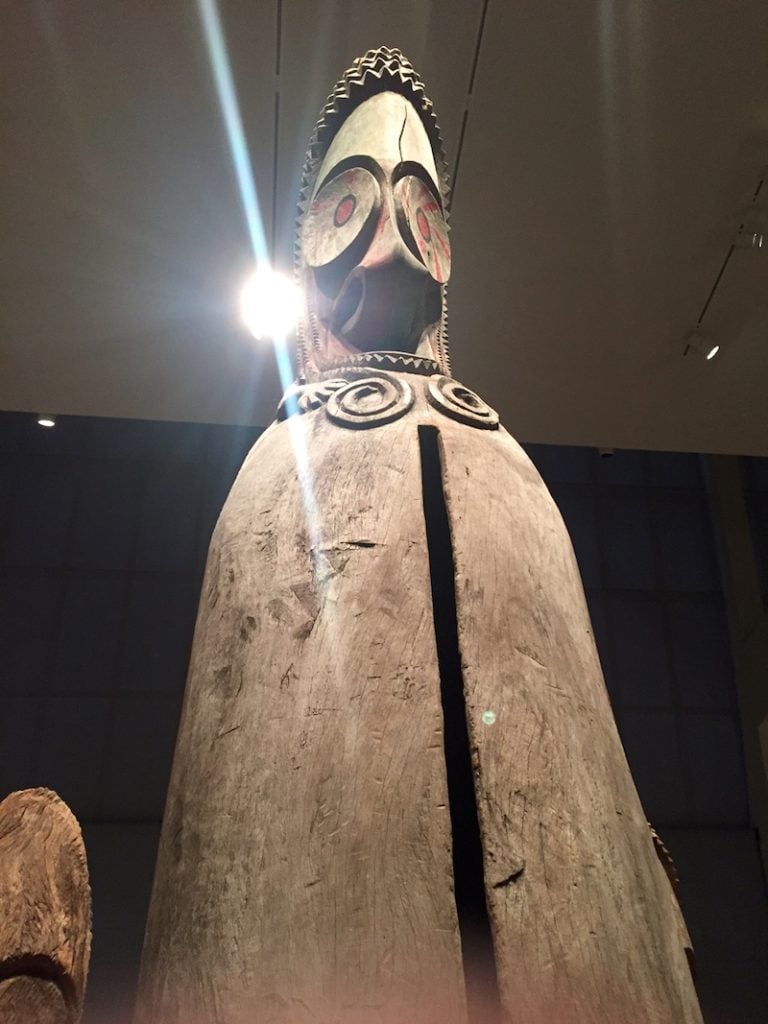

Tin Mweleun, commissioned by Tain Mal, slit gong (Atingting Kon), mid-to-late 1960s. Image: Ben Davis.

Tin Mweleun, commissioned by Tain Mal, slit gong (Atingting Kon), mid-to-late 1960s

A stunning functional sculpture, meant as a ceremonial drum, though with those dazzling eyes, carved nostrils (designed to be adorned with flowers), crowning spikes to evoke the texture of hair, and curved necklace suggesting the tusk adornments characteristic of a figure of high status.

The notes on the piece’s authorship are interesting: The commissioning chieftain—in this case, Chief Tain Mal—is generally credited as the author of such slit gongs, but in this case, the carver, Tin Mweleun, was particularly well-known for the magical recipe he used for the carving. It stands as a towering testament to the cultural vitality of Vanuatu, a Pacific island nation facing annihilation before the rising waters of climate change.