Archaeology & History

‘X’ Marks the Spot: Inside History’s Most Thrilling Treasure Hunts

A cultural obsession with buried booty stretches back across the centuries.

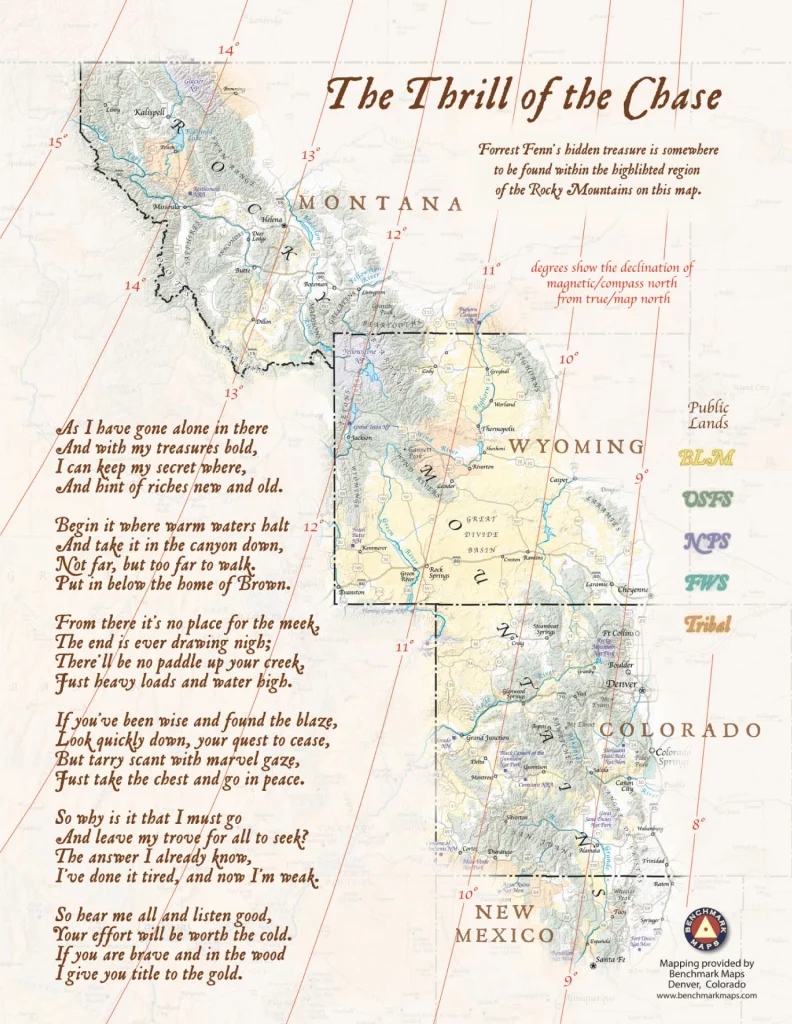

In 2010, the eccentric art dealer Forrest Fenn, who believed he was terminally ill, buried a stash of bronze treasure worth $2 million in the Rocky Mountains. At the same time, he published a memoir, The Thrill of the Chase, which reportedly contained the key to the treasure’s location.

Ten years later, the treasure was discovered by a medical student, Jack Stuef, following the deaths of five other treasure hunters, and just a few months before Fenn’s own demise. Stuef sold the treasure, which later went up for auction, but to this day he refuses to disclose the secret of how he cracked the code, or where he found the loot.

The Fenn story has many of the hallmarks of an ongoing obsession with buried treasure that reached fever pitch in popular culture in the 19th century and has never really abated. A secret code or map, passed on by a proprietor who is (or at least thinks) they are on their deathbed, reveals the location of untold riches.

A set of items from Forrest Fenn’s treasure. Photo by Lynda M. González/Heritage Auctions.

As a cultural trope, buried treasure is almost entirely divorced from reality. We all know, courtesy of Robert Louis Stevenson and the myriad spoofs he has spawned (ranging from the Muppets to the Simpsons), that “X marks the spot.” It’s hard to name another cultural phenomenon that completely embodies the world of hearsay, legend, and calculated fiction.

Great quantities of treasure have, of course, been unearthed by archaeologists and metal detectorists over the centuries. However, the distinguishing feature of this particular mythos is that it is buried with the intention of one day being found. Discounting contemporary tribute acts such as Forrest Fenn’s, there is—astonishingly—not a single verifiable case of treasure having been deliberately hidden away with its location encrypted, and being subsequently discovered.

Much as unicorns and dragons have their roots in interpretations of narwhals’ tusks or dinosaurs’ teeth, the notion of a mysterious hoard of loot being uncovered by hardy clue-busters has its origins in one small kernel of historical fact. It takes the form of Captain William Kidd, who in the late 17th century found fame as a pirate hunter, protecting English maritime interests in North America and the West Indies, before succumbing to the temptation to turn pirate himself.

Knowing that he was a wanted man, he (allegedly) buried a large part of his booty somewhere along the East Coast near Long Island, hoping to make use of the secret to bargain for his freedom. The gambit failed, and once he was captured in 1699, he was shipped back to England and executed in 1701.

Forrest Fenn’s downloadable treasure map as prepared produced in partnership with Benchmark Maps in Denver, CO.

More than a century later, Washington Irving wrote in Tales of a Traveller (1824) that Kidd’s history had “given birth to an innumerable progeny of traditions.” Most concerned the “circumstance of his having buried great treasures of gold and jewels,” which had “set the brains of all the good people along the coast in a ferment.” There were “rumors on rumors […] of coins found with Moorish characters, the plunder of Kidd’s eastern prize, but which the common people took for diabolical or magic inscriptions.”

Tales of maritime adventure had been sensationally popular ever since Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719), but Irving’s short story Wolfert Webber; or, Golden Dreams (1856) was the first to employ the motif of buried treasure. A “worthy burgher” on Manhattan Island, Wolfert Webber is visited by a dream disclosing to him the whereabouts of Captain Kidd’s stash.

The Life & Adventures of Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe. First published London, 1719. Illustration from 1895 edition. Photo: Culture Club/Getty Images.

Speaking of his debt to Washington Irving, Robert Louis Stevenson declared that “plagiarism was rarely carried farther” when he came to write his own Treasure Island (1883). This might be overstating the matter, given that X-marked treasure maps and one-legged pirates with parrots on their shoulder were very much Stevenson’s inventions.

However, there is another early source for our obsession with buried treasure that has been just as influential. Edgar Allan Poe’s short story The Gold-Bug (1843) also hinges upon a search for Captain Kidd’s fabled fortune. Poe’s contribution, however, was to introduce something rather different to the genre. A cipher that looks like this:

53‡‡†305))6*;4826)4‡.)4‡);80

6*;48†8¶60))85;1‡(;:‡*8†83(88)

5*†;46(;88*96*?;8)*‡(;485);5*†

2:*‡(;4956*2(5*-4)8¶8*;40692

85);)6†8)4‡‡;1(‡9;48081;8:8‡1

;48†85;4)485†528806*81(‡9;48

;(88;4(‡?34;48)4‡;161;:188;‡?;

In the story, the golden scarab beetle of the book’s title—discovered by William Legrand, an erudite but oddball naturalist on Sullivan’s Island in North Carolina—is wrapped in parchment for safekeeping. This wrapping is accidentally held over a fire, at which point it reveals secret markings including an image of a goat, and the cryptic series of numbers and symbols above. Legrand then recounts the tale of how he has been able to crack the code.

The fixation with cryptic texts has a pedigree that stretches far back into antiquity, but Poe’s genius was to combine this with a contemporary obsession with adventure stories.

Then again, if one particularly strange legend is to be believed, perhaps it was not entirely new. In 1885, an anonymous pamphlet appeared, titled The Beale Papers. It told of one Thomas J. Beale, who in January 1820 rode into Lynchburg, Virginia and checked himself into the Washington Hotel. Beale spent the rest of the winter there, charming “everyone, particularly the ladies,” before disappearing as mysteriously as he had come. Two years later he returned, this time entrusting a locked iron box to one Robert Morriss, the proprietor of the hotel, which he said contained “papers of value and importance,” before once again vanishing.

Morriss’s patience finally cracked after 23 years and so, in 1845, he prised open the box. What he found were three sheets full of ciphers and a handwritten note, explaining that Beale had struck gold along with a traveling party of 29 others, journeying across the American frontier in search of buffalo. Beale had been selected by the party to find a secure place for the riches, hence his first visit to Lynchburg.

The second trip was in part to deposit more riches, but also to ensure that a trusted third party would allow the hoard to find its way to the men’s families, should anything happen to them. The note promised a letter containing the key to the code. That letter never arrived.

Illustration from Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson. First published in 1881-82. Photo: Bridgeman via Getty Images.

Morriss spent the rest of his life trying to unscramble the mystery, without success. In 1862, when he knew he was dying, he passed on the secret to a friend—the anonymous author of the pamphlet. This person made a significant breakthrough.

Acting on a hunch that the “J.” in Beale’s name stood for “Jefferson,” he worked out that the numbers in the second Beale cipher correspond with words in the Declaration of Independence, and so uncoded a full description of the treasure that was to be found: “Two thousand nine hundred and twenty one pounds of gold and five thousand one hundred pounds of silver; also jewels, obtained in St. Louis in exchange for silver to save transportation”.

That amounts to more than $60 million in today’s money. However, the key did not work on the other two pages that presumably held the answer to the treasure’s location. Two decades later, the despairing pamphleteer published his account in the hope that someone else might have more luck.

Many have since tried to decipher Beale’s papers; all have failed. For a while, credence was given to a rumor that Poe somehow orchestrated it all from beyond the grave.

Carl Hammer, an influential figure in computerized codebreaking, declared in 1999 that the mystery had occupied “at least 10 percent of the best cryptanalytic minds in the country. And not a dime of this effort should be begrudged. The work—even the lines that have led into blind alleys—has more than paid for itself in advancing and refining computer research.”

As far as buried treasure is concerned, perhaps the story really is its own reward.