Pavlo Makov, the artist representing Ukraine at the country’s Venice Biennale pavilion this spring, was supposed to go to a shooting range on Friday with his friend who is a trained soldier.

The 63-year-old conceptual artist had already undergone obligatory military training during the Soviet era, but he felt it was time to “refresh a little bit, just in case.”

On Thursday, the plans were cancelled when Russian troops began a land and sea invasion of Ukraine after weeks of icy standoffs and fraught attempts at diplomacy.

“We are hearing all morning the sounds of bombs,” the artist told Artnet News from his three-room house in Kharkiv, the country’s second-largest city, where he lives with his wife—his son, daughter-in-law, and 92-year-old mother are sheltering with them at their house.

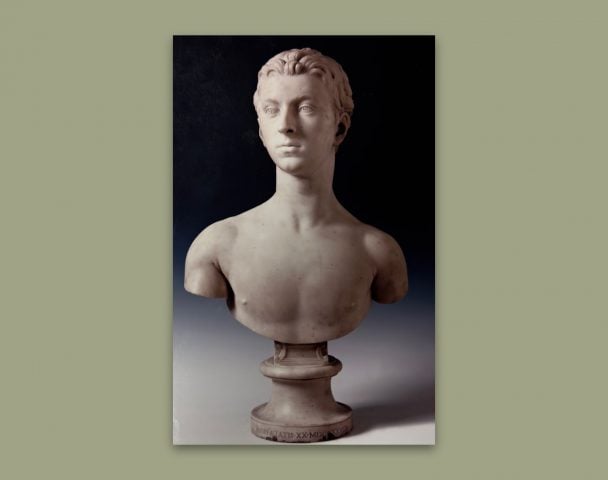

Pavlo Makov. Courtesy the Ukrainian Pavilion.

For the moment, Makov was calm. A few Russian tanks were in the streets, and people were queuing at the supermarket and gas station; the internet was still working and the television was on. Watching and waiting with his family, Makov was able to keep in touch with the curators of his upcoming pavilion, Lizaveta German, Maria Lanko, Borys Filonenko, all of them in Kyiv, regularly.

“You have to understand that we have already lost 15,000 soldiers during the last eight years,” he said, referring to the aftermath of the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014. “Europe was thinking this is a small conflict somewhere else. But this is a conflict on the eastern border of Europe. For the past eight years, the West was not accepting what was happening here: a war against a civilization they represent. This is not a war between Ukrainians and Russians—this is a war between two civilizations and two mentalities.”

Makov is ethnically Russian. He was born in St. Petersburg but spent most of his life in Ukraine and studied fine art in Crimea as well as graphic art. His practice often takes the form of fine line etchings, as well as prints and drawings—he also makes large-scale sculptures and his work has been been displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Met in New York.

“I am a citizen of Ukraine, and for me citizenship is much more important than my ethnic identity,” he said.

For the Venice Biennale, which opens in April, the artist is creating an updated version of his 1995 work The Fountain of Exhaustion. The piece—a three-meter-square wall installation with water tumbling down 78 bronze sculpted funnels—was originally about “the absence of vitality in society after the Soviet Union,” the artist said. “Now, so many years later, the situation is changed, and it is about a global exhaustion. We are facing a lot of existential problems, not only with nature, but also via fake news and politics.”

Makov and his curators were hoping to send the work to Venice in two weeks, but the invasion has made that uncertain. “Nobody knows now what will happen,” Makov said.

A 3D rendering of The Fountain of Exhaustion. Courtesy the artist.

The artist said that, over the past years, he and other artists have been working to support Ukrainian defense efforts. One friend of the artist who happens to be a soldier in the Donbas region, which has been claimed by Russian separatists since 2014, was able to use funds from a sale of one of Makov’s artworks to buy armor and weaponry.

“It wasn’t enough to buy everything that he needed,” Makov said. “He was able to buy a new machine gun and a bulletproof vest. Everyone is doing what they can.”

The Ukrainian added that he was surprised that artists from Europe have continued to work with Russia after the annexation of Crimea while saying little to nothing about its ongoing aggression, citing projects taking place at venues like the VAC foundation and the Garage Museum. “Russia is doing everything to be represented in the best way from the point of view of culture,” he said. “But the fact is that the country truly is against you and hates you.”

Though his works have been in the collection of the Pushkin Museum since the 1990s, Makov severed ties with the country after the invasion eight years ago.

“I lost all connections with Russia when the war started in 2014, all my interests and connections with galleries there,” he said. “From my point of view, it is impossible to work with another country that is openly and aggressively attacking your country, and that is taking your territory.”

For now, he has no plans to leave Kharkiv.

“I am not running from my home, though I cannot really fight and I do not know how to do it. You need to be trained. Let’s see what will come next. Russia won’t stop just like that. They will continue to fight. But so will we.”