When the Swiss entrepreneur Uli Sigg first traveled to China in 1979, he hesitated to reach out to artists because he feared that making contact might get them into trouble with the authorities. But in the more than 40 years since then, he has assembled perhaps the world’s most important collection of Chinese contemporary art in close collaboration with China’s leading creatives. Ai Weiwei has said of Sigg: “However famous I become, he [Sigg] is the creator.”

The former Swiss ambassador to China is still working to help foster the careers of emerging talent today as the sponsor of the Sigg Prize, which gave its inaugural HK$500,000 ($64,000) award to the Hong Kong artist Samson Young earlier this month. An exhibition of the winning installation, as well as work by the five other shortlisted artists, is on view at the recently reopened M+ Pavilion in Hong Kong (which had been shuttered for months during the city’s lockdown).

The show could take on a heightened significance following the passage last week of a new national security law to suppress subversion, secession, and terrorism in the semiautonomous city, which local arts workers have warned will cause “incalculable” damage to Hong Kong’s status as an art hub. That status is particularly important to Sigg, who in 2012 announced plans to donate more than 1,000 works in his collection to M+, the long-delayed museum of visual culture that is finally expected to open in the West Kowloon Cultural District next year. So far, Sigg maintains that awarding the collection to Hong Kong was the right move—it will keep the artwork within China while offering the maximum freedom for display.

Following the announcement of the Sigg Prize winner, we spoke to Sigg over the phone from his home in Switzerland about his thoughts on the future of Chinese art, how the lockdown has hampered his collecting process, and the unintended impact that growing anti-Asian sentiment could have on art.

The inaugural Sigg Prize, which was awarded to Samson Young earlier this month, is an outgrowth of the Chinese Contemporary Art Award you founded in 1998 to honor artists born or working in China. How does the new award, administered by M+, relate to the original?

My intention remains the same: to bring talented artists to the attention of the Chinese public. At the beginning when I set it up in the 1990s, the wider audience did not have much interest in contemporary art, and although the concept has changed over time in terms of opening up to greater China, the purpose remains the same, and I see the Sigg Prize as doing that too, on a larger scale and with more resources, which of course is to my delight.

Samson Young. Photo: Winnie Yeung @ iMAGE28. Courtesy of M+, Hong Kong.

What will the future of the prize be? Will it accept entries from other states in the region, not just greater China? Is it less about the ethnicity or nationality but more about where they work?

The main idea will remain the same: it’s about work that is created either in the ambiance or in the reality of greater China, maybe by people who are coming out of this particular sphere. Of course, that doesn’t limit whatever they deal with in their work. It’s not so much about borders or nationality; it’s about cultural space, Chinese cultural space.

Can you say a few words about why Samson was chosen? He won for his installation Muted Situations #22: Muted Tchaikovsky’s 5th, a 12-channel installation that captures the Flora Sinfonie Orchestra playing Tchaikovsky with only the sounds of performers shuffling in their seats and scraping their bows, with no musical notes.

What I really liked was the ease with which he crossed over all of these limitations of what normally would be the music world, the performance world, video art, etc. That particular approach impressed me very much.

Samson Young, Muted Situations #22: Muted Tchaikovsky’s 5th, (2018). Courtesy of the artist Installation view, 2019. Image: Winnie Yeung @ iMAGE28 Courtesy of M+, Hong Kong.

His work has broken down a lot of boundaries.

Across all mediums, yes. For me, the worlds of music and contemporary art have very little overlap, so to see how he merged the two was very impressive. The whole series comes as a surprise to the people in the contemporary art field and the music field, and can reveal new aspects of both.

Work by the other finalists was also exhibited in the Sigg Prize 2019 exhibition at the M+ Pavilion. In general, what impressed you the most? What were you looking for—the perspective of the artist, and their ability to give us a different perspective into contemporary life?

Yes, all of the above. To become a finalist, we looked at two years’ worth of work for each artist, and then the finalist submitted a work to the exhibition, and we chose the single work for the winner. They all have a degree of intensity and involvement, and formally interesting results. So that’s how they became finalists.

M+ Building rendering. © Herzog & de Meuron.

Besides the prize, I’m also interested in the status of M+. When can we visit the museum?

Well, I’m not exactly the person to ask about that. But hopefully there will be a soft opening in March and then the big splash should be in July. That’s the plan as far as I know. [An M+ representative later stated that the building will be complete by the second quarter of 2020, with a public opening nine to 12 months later.]

And are there any things that worry you in regards to the opening of M+? This year has been challenging for everyone because of the coronavirus pandemic. How do you think the pandemic might have changed the way we look at, think about art? And the way we think about life?

I don’t know what the outcome will be, and neither does anyone else. Of course, the consumption of art in a public space such as a museum will be much inhibited, and no one is happy about that, but there’s not much we can do. I see it here in Europe currently.

I have a show of my own collection at the Castello di Rivoli near Torino, which is a region that has been really severely affected by the virus, and so now they are just in the process of defining how to give access to a public unknown in numbers at this moment. Many people are hungry to just get out and see new things. No one knows at this stage, so a prognosis may be much easier two months from now.

Installation view of “Facing the Collector. The Sigg Collection of Contemporary Art from China” at Castello di Rivoli.

What is the exhibition at Castello di Rivoli?

The show is called “Facing the Collector,” and it came about because two years ago, the institution received a big donation from an industrialist [the late Francesco Federico Cerruti] who put together a very large collection ranging from Old Masters to some Modern and contemporary works, and [acquired] even the house where all of this was situated, from a collector no one knew about, had any idea about. So now, they’ve restored that collection and the house so it can be open to the public, and that really piqued their interest in collectors.

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the director of Castello di Rivoli, was interested in pursuing this idea of the collector, the person behind the collection. There are many portraits of me in the show, but it also addresses the way I built my collection, my “typology” of collecting, and also how I commission works.

Whenever we talk about collectors or a show from the collectors it’s usually about the work, but it’s interesting to shift the perspective.

It’s just a pity that the exhibition didn’t take place as planned. It was open for one week and then it had to close; it was really caught in this virus problem.

Installation view of “Facing the Collector. The Sigg Collection of Contemporary Art from China” at Castello di Rivoli.

How do you see the current situation in Chinese contemporary art right now? In speaking to artists, there seems to be a very strong desire for them to document or record their experiences and their observations, the emotional turmoil that they have gone through during this period. It seems to be a more direct and timely response to what is happening around them, and also, of course, the most direct way to disseminate those visuals is via social media, regardless of the platform. Do you think this could be an important time of transition?

In times of high tension and changing circumstances, artists are often drawn to act and make interesting art… it very much depends on the individual. Some need long-term reflection to come up with a very well thought-out work, and some artists’ method is to react spontaneously. Still others will just document without much value added. There are so many ways to respond to these extraordinary situations, and we see all of that. Some of it is interesting, and some is really not. Some will surely prevail beyond the virus time, and much will disappear.

And of course there are new distribution methods with social media. For me, that’s a big disadvantage, being unable to travel and seeing it all from Switzerland, I don’t have access to Chinese social media and I cannot read Chinese—I can speak it, but I cannot read it. So for me, it’s difficult to follow in the same ways I normally do.

Recently I saw in the Guardian that the anti-Asian crime rate has increased by 20 percent, and statistics like that have been emerging since the onset of the coronavirus. Do you think that collectors and supporters of the art world in China should take the lead in maintaining these kind of relationships?

Of course, the art world should take the lead in combatting this anti-Asian sentiment, but unfortunately I don’t know that it will be able to do that. These types of prejudices right now are mainly fuelled by the President of the United States; it’s become an instrumental part of his re-election campaign and it spills over to Europe as well.

I’m afraid it may have some effect on public institutions not focusing as much on Asian art as they may have otherwise, so it may in fact be more difficult to get sponsorship for Chinese art, for example. How long will it last? We don’t know.

It’s very sad, because selection processes should be based on the quality of the art, and shouldn’t be subject to these global political swings, which in this case are particularly irrational.

Visitors in the M+ event space. Courtesy of M+.

That means that M+ will have an even bigger role to play in terms of carving a different narrative.

An institution like M+ can take a fresh view, without issues of the past weighing on it. It can build the right relationships, and even enhance the role [for art] to play.

I want to hear what you think about Hong Kong right now. Do you think the role of Hong Kong within the art world will change amid the ongoing political turmoil?

I think a lot is in the hands of the people of Hong Kong and mainland China… of course that’s easy for me to say from a distant Switzerland, to talk about it without being able to travel and hear it directly from those on the ground. But I do hope that all sides involved will take a step towards each other because the future of Hong Kong as an arts hub is at stake. People will still have to want to travel to Hong Kong, and the restrictions on that will really inhibit it. The free movement of people, art, and freedom of speech are all very important. That’s what made Hong Kong the place it is now.

Is this threatened further by the new national security law?

It would be naive not to assume that there is a risk, whether this risk will materialize will depend on how the HK authorities will implement this law. And whether the various camps are enabled and also willing to take a step towards each other out of current deadlock. Without international and mainland travel, the art-trading hub Hong Kong will clearly suffer.

Yes, the value of Hong Kong has always been that it is kind of on its own, you know—things can happen in Hong Kong. Personally, I’m also worried about your collection. How much of it can be or will be shown?

I must really stress that so far we have not been inhibited in the least in preparing our exhibition, and I have very strong commitments from the chairman [of West Kowloon Cultural District, where M+ is located], the director of the museum, the CEO—each and every one of them has expressed the strongest intent to preserve the current status in this respect and not allow any restraints. Of course, that has happened in the past, and this current situation is momentary, but I see no reason to doubt these assurances.

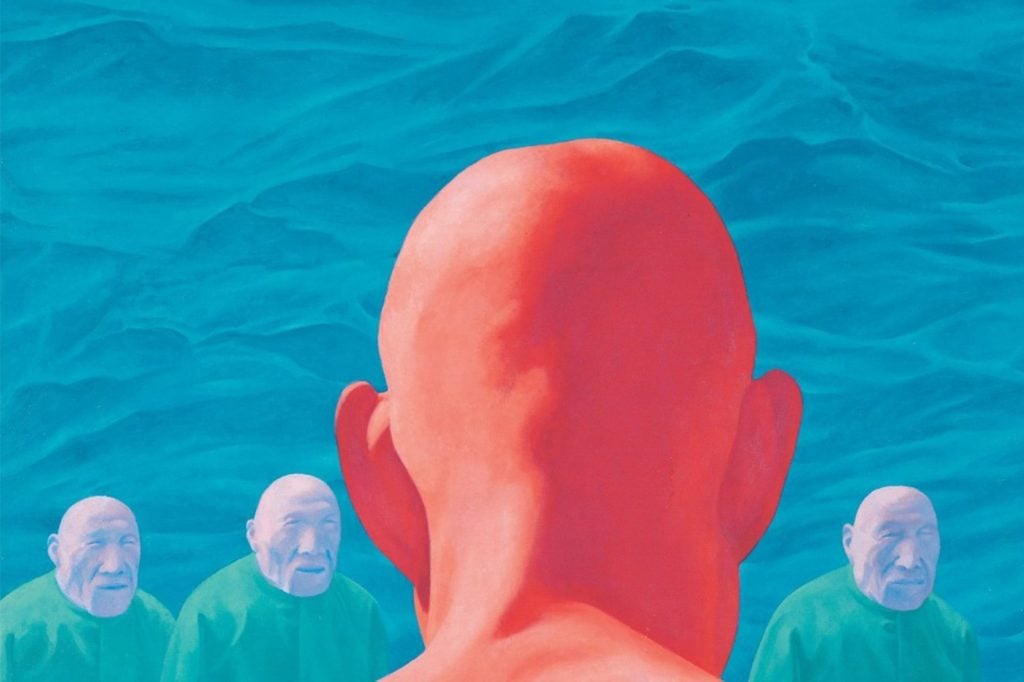

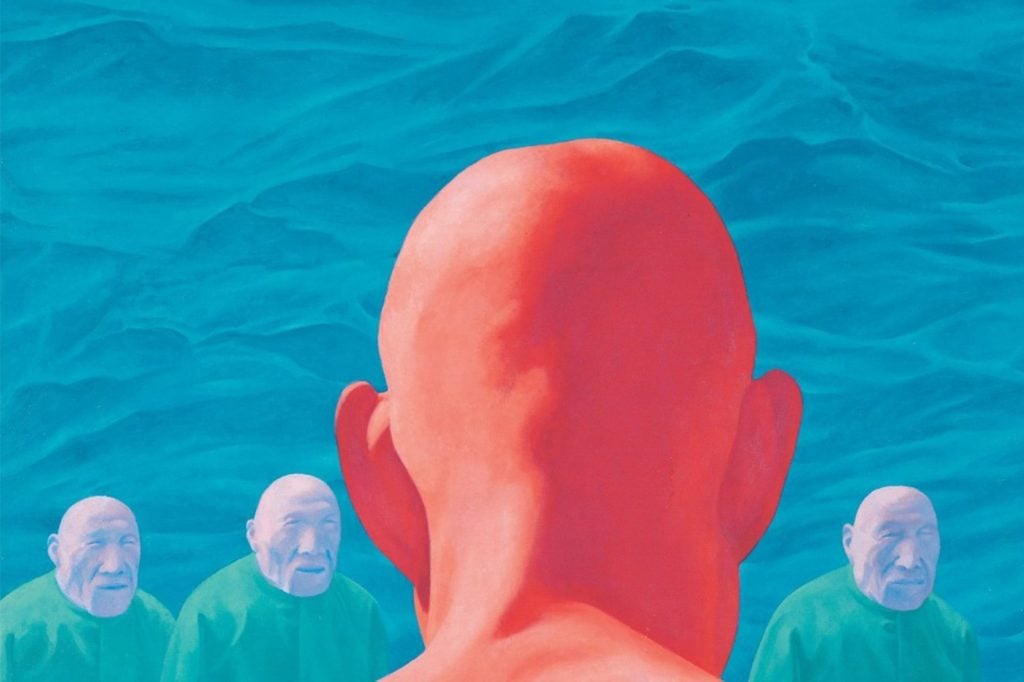

Fang Lijun, Untitled (1995). Courtesy Uli Sigg.

And people should take note of the significance of having your collection in Hong Kong, as opposed to anywhere else. Despite the complicated historical backdrop and relationship between Hong Kong and mainland China as well as their different trajectories, the historical and cultural context of Hong Kong is inseparable from the Chinese cultural sphere you mentioned. It is important that these works can remain and be exhibited in Hong Kong, which is a part of the Chinese soil, culturally speaking.

That’s always been my ambition. It’s the only place one is able to read the story line of Chinese contemporary art and far beyond that, from the collection. It has an importance, and I’m still convinced it is in the right place, even if we have to wait 20 more years for it to be shown!

Again, this collection is not about me at all, it’s about the Chinese artists and what they have created, and that is a value which remains eternal. Even if conditions are worse for a limited time, better days will come.

It’s also an important chapter of history, what the collection embodies. I personally learned so much from just seeing a fraction of the works, because we were not taught about that period of history—from the 1970s onward—in school back in the day. It is a great way to be exposed to that period of time.

I’m convinced one can see, learn, understand, feel, grasp more from art than from reading 100 books about it. That is the meaning of the collection.

Zhang Xiaogang, Bloodline Series—Big Family No. 17-1998 (1998). Courtesy of the artist and West Kowloon Cultural District Authority.

I’m also curious about the way you collect these days. Has anything changed from your practices in the past?

Of course it is very different from the past. There’s no need for me to collect in an encyclopedic way now that there is M+ and many collectors both inside and outside of China. Now, I can focus on fewer artists and artists who I particularly like. That was not the criteria in my collecting before, when I just wanted to mirror the art production of a whole period. I commission works—that’s what I enjoy, sometimes getting involved in the creative process—and that’s my way of researching phenomena in China. Of course, right now, it’s very difficult because that requires some physical presence and dialogue, which is very difficult to do online. I hope I can resume my own way of collecting soon.

How does it work exactly, the process of commissioning?

It varies, but I’m interested in how the individual artist works. I may have a topic in mind, take “China Dream” for instance, so that subject I research as a China specialist. It’s an interesting way for me to work, and if the artist is interested in getting involved, I get to add my personal views to it and enrich the conversation. That’s the most interesting way for me. Sometimes artists want to go their own route, but the first way is the most rewarding for me.

Many artists really like my involvement; they claim I’m an artist, but I’m not! Yes, oftentimes I have better ideas than the artists, but there is a big divide. We all talk about it, but the artist actually does it.