Up Next

Rising Artist Ronan Day-Lewis’s ‘Punk Romanticism’ Imbues Desolate American Landscapes With an Eerie, Cinematic Aura

The artist's oil pastel paintings have been earning the attention of galleries and critics alike.

The artist's oil pastel paintings have been earning the attention of galleries and critics alike.

Katie White

A strange, animal-like being appears in each of emerging artist Ronan Day-Lewis’s haunting, mystical oil pastel paintings. He calls this entity only “the creature.”

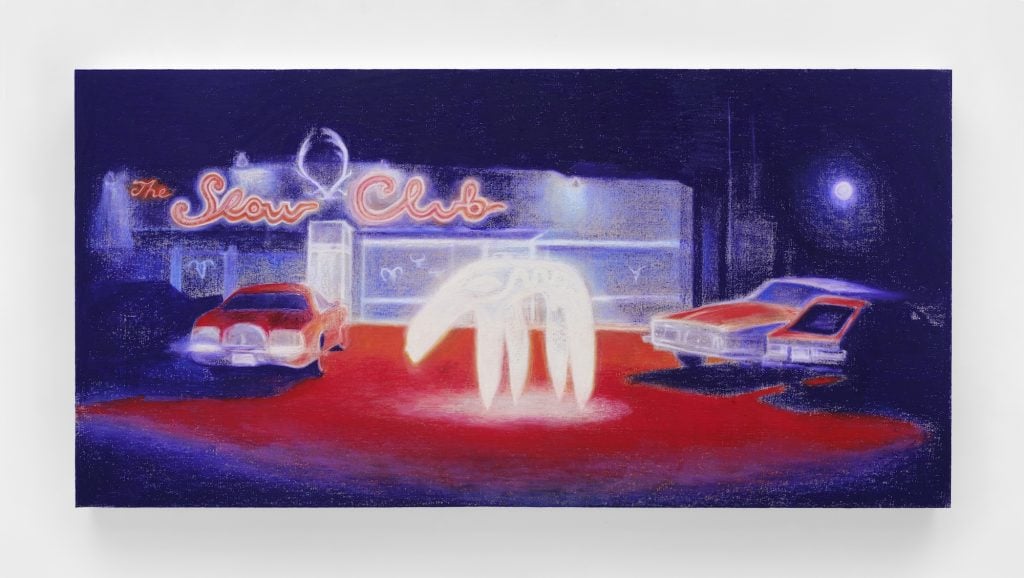

The creature hovers at gas stations and lonely desert landscapes, glowing and almost phosphorescently white. At the end of its long giraffe-like neck is its startlingly human face. In the artist’s recent debut solo exhibition “The Friend” at New York’s D.D.D.D. earlier this summer, the creature appeared in every one of the artist’s eerie, nocturnal compositions, as well as in three dimensions. Day-Lewis constructed a sculpture, the first of his practice, of the creature, which he made entirely from melted wax. At about the size of a pony, it weighed 250 pounds.

The 25-year-old artist says he can feel somewhat possessed by this creature born of his imagination, yet he resists the urge to define it, even name it more clearly. “I think that would kill it,” he explained to me, at his Ridgewood, Queens, studio. Instead, he lets it roam freely through his canvases, an ambiguous monster he doesn’t quite understand.

Day-Lewis says this being first entered his work about five years ago, while he was still a student at Yale. “I was in class making these unconscious drawings, sitting on the floor of a classroom. The teacher had a movie playing in the background. I was sketching and, at some point, a face emerged through a crude charcoal drawing. I wasn’t looking in a mirror, but I interpreted it as a self-portrait,” Day-Lewis explained. “I couldn’t quite put my finger on it though—a face and this elongated neck and the suggestion of a kind of pastoral environment, but nothing really definite. Over the last few years, the form has suggested itself to me more fully.”

Ronan Day-Lewis, The Friend (2023). Courtesy of the artist and DDDD Pictures.

Benevolent and frightening at turns, the creature recalls both the unearthly majesty of an ancient Assyrian lamassu and the hellbound mutants of Hieronymus Bosch’s world. These transportive, otherworldly tensions have been earning Day-Lewis the attention of galleries and critics alike.

At Spring/Break’s February 2022 Los Angeles edition, a presentation of his work “See Through” by Brooklyn’s Tomato Mouse, was a fair favorite. Last fall, the artist’s work was included in a Jerry Gogosian-curated sale of rising artists at Sotheby’s. In the coming months, Day-Lewis has work slated for inclusion with Galleri Urbane for a presentation at the Dallas Art Fair as well as in a forthcoming Two x Two auction. His works are, as some have noted, impressively reflexive, pushing back against any neat conclusions; with an air of mutability, they hint that the story might suddenly unfold.

Ronan Day-Lewis, Playing House (Let’s Set Everything On Fire) (2023). Photo: Caroline Wallis. Courtesy of the artist.

“Ronan’s overlapping of personal, family, biblical, and even fairytale narratives suggested to me how stories form and interpret our experience. The works are both childlike and sinister,” said artist Rebecca Bird, who runs Tomato Mouse. She added that since she first showed his work in 2021, “his processing of memory and image has become more omnivorous, but always through the diffusion lens of layered glowing oil pastel and the gentle, lumbering, somnambulist creatures that are his protagonists and alter egos.”

Day-Lewis pulls these works from his imagination, drawing directly onto unprimed canvases, and references images on his phone if he needs to. He prizes pastels for their ability to build up color, creating a haziness that suggests film grain. He usually plays music to get himself into a kind of trance while he works. (“Slowdive and other shoegaze bands have been good for that,” he told me; “Without Stopping” by Bowery Electric and Brain Eno’s Another Green World album have been on repeat, along with Kurt Cobain’s early home-recorded demos.)

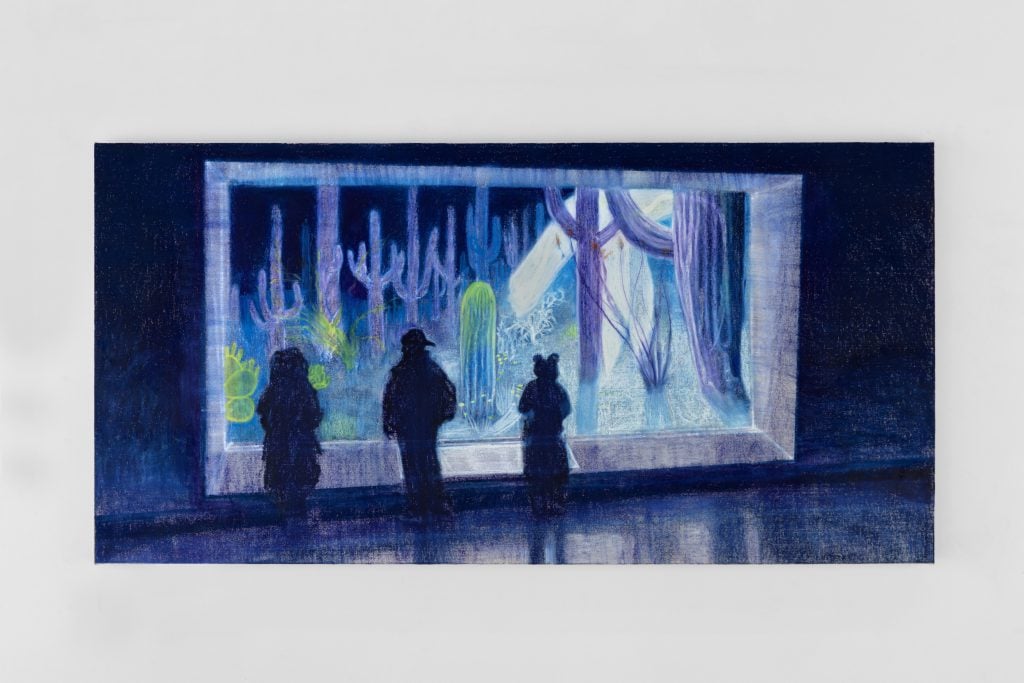

Over the past year, his compositions have leaned into shades of blue, the terrains more firmly situated in a version of the American West taken from sometime in the past. The artist, who was raised in rural Ireland, spent several months in Marfa, Texas, as a child, an experience that was deeply formative for him. Similarly, childhood trips to the American Museum of Natural History, where he marveled at the carefully constructed—yet inaccessible—dioramas also helped shape his fascination with the natural world, both for their intricacy and the odd sense of frozen time (in fact, the museum itself appears in several of his recent works).

Ronan Day-Lewis, Are you there right now? Do you ever get lonely? (2023). Photo: Rachel Kuzma. Courtesy of the artist.

“My work is definitely in dialogue with Romanticism. I’m drawn to this idea of projecting human emotion onto landscapes and places,” he explained. “The sublime, to me, is the outside looking in. I sort of make sad paintings. But there’s also a pleasure in longing—without unfulfilled longing, there’s no wonder. Vast, empty spaces like the desert of the American West excite me because the lack of objects, structures, and signifiers that usually make up your identity makes room for a kind of spiritual lightness.” While his works engage with the natural world in a way that is reminiscent of that 19th-century art movement, they also inject a bit of edge. “I call it punk Romanticism,” he said, with a gentle laugh.

His art-historical inspirations are numerous, however, and deeply held. He counts among them J.M.W. Turner for his violent seascape; Edward Hopper for his stillness; and Pierre Bonnard for his wild sense of color. He also admires Alex Katz, Christina Quarles, Francesca Woodman, Francis Bacon, Georgia O’Keeffe, Forest Bess, René Magritte, and Leonora Carrington.

Alongside his creatures, tornadoes have begun to appear in his compositions with frequency. “I used to have these nightmares of natural disasters, more tsunamis than tornadoes. There’s something just really fascinating about vast natural phenomena that are so outside of human control,” he said. Lately, he has been looking at YouTube videos of storm chasers, fascinated by their attraction to danger. But these tornadic visions are also another form of quintessential Americana, seemingly plucked from Wizard of Oz, and couple a sense of nostalgia with dread at the loss of a past we can never reclaim.

Film’s influence on his work is self-evident. Day-Lewis is a filmmaker himself (he is the son of actor Daniel Day-Lewis and filmmaker Rebecca Miller) and has been laboring over a project of his own for years. In his embrace of the monstrous ecstasy of the quotidian, David Lynch is a notable reference. “Blue Velvet has given me a lot lately,” Day-Lewis said. He also credits “Badlands and Paris, Texas for their aching Americana. Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now for its suffocating sense of dread. And Pan’s Labyrinth for the dark beauty of its mythology.” The list could go on.

Ronan Day-Lewis, The Slow Club (If You Receive A Love Letter From Me You’re Fucked Forever) (2023). Photo: Frankie Tyska. Courtesy of the artist.

When asked what he’s after in these works, Day-Lewis said he believes that his art has a bit to do with wish fulfillment, with an ability to create places he’d like to reach. “For me, the creatures are a kind of haunting, but a haunting of the past by me in the present,” he explained. “My sense of Americana has always been that of an outsider. There is something sort of absurd about me, in this urban environment so detached from nature, drawing these deserts and the West. It’s an intense yearning for something that maybe doesn’t exist.”

Turning his eyes to look over a new work, just begun, showing a tornado behind parked cars, on his studio wall, Day-Lewis considered, “The American pastoral is really the landscape of the subconscious.”