So much of the art world orbits around questions of value, not only in terms of appraisals and price tags, but also: What is worthy of your time in These Times, as well as your energy, your attention, and yes, your hard-earned cash?

What is the math that you do to determine something’s meaning and worth? What moves you? What enriches your life? In this new series, we’re asking individuals from the art world and beyond about the valuations that they make at a personal level.

Aric Chen knows a thing or two about culture—he’s defined a career at the nexus of architecture, design, and digital worlds. Two years ago, Chen became director of Rotterdam’s esteemed Nieuwe Instituut, famed for its critically rigorous and avant-garde design-focused presentations. This month, Nieuwe Instituut will open “Workwear,” an exhibition that explores the transformation of functional laborers’s clothing into fashion symbols seen on runways and metropolitan centers alike.

Prior to Nieuwe Instituut, Chen was the curatorial director of the Design Miami fairs and, from 2012 to 2019, was the founding lead curator for design and architecture at Hong Kong’s visual culture museum, M+.

Chen relocated from Shanghai to Rotterdam and is now in the midst of renovating his biggest recent purchase—a 1904 house just a short walk from the museum (and where Lee Harvey Oswald may have spent the night).

We recently caught up with Chen, who shared some in-process pics of his pad, told us the cause he has no problem getting behind, and why his ability to deal with difficult personalities is his blessing and his curse.

Construction on Aric Chen’s new apartment. “It’s a commitment,” he said. Courtesy of Aric Chen.

What is the last thing that you splurged on?

I just bought an apartment in Rotterdam, which I see not so much as a splurge, but a commitment! It’s less than a 10-minute walk from the Nieuwe Instituut in an old 1904 house. Supposedly, in 1962, Lee Harvey Oswald spent a night in what’s now my kitchen while on his way from the Soviet Union, where he had defected, to catch a Holland America Line ship back to New York. That’s the story, but as always with Oswald, there are unanswered questions.

What is something that you’re saving up for?

New skylights. I’m doing some work on the apartment, and those are next on the list.

The skylights in Aric Chen’s apartment. Courtesy of Aric Chen.

What would you buy if you found $100?

I’m always told I’m woefully short on cooking supplies, so I suppose I’d stock up on those. But I’m not such a cook. If I had to choose, I’d be the one doing the dishes.

Research Center. Courtesy of Nieuwe Instituut.

What makes you feel like a million bucks?

Honestly, the staff and visitors at the Nieuwe Instituut—as long as they’re happy, too. We’re a fairly large, complex, and strange beast. But I have to say, that’s what makes me feel like I have the best job in the world. We have an incredible collection—the Dutch national collection of architecture and urban planning—while also working across the fields of design and digital culture, with a deeply embedded culture of experimentation that pushes us to rethink critical issues around the past, present, and future—at local, national, and planetary scales, with a role in policy, and so on. We aren’t just a place for exhibitions, discussions, and debates, but a testing ground for new ideas, working with a broad range of audiences and collaborators, and it’s all of this that keeps me going each day.

What do you think is your greatest asset?

I would like to say it’s my towering intellect and winning smile, but in real life, it’s probably more like an ability to deal with difficult personalities, which is both an asset and a curse. Another answer to this might be my curiosity. Perhaps the two are related.

Nina van Hartskamp’s Worlds Within (2022) in “In Search of The Pluriverse.” Courtesy of Nieuwe Instituut.

What do you most value in a work of art?

I like art that makes me feel just a little bit uncomfortable. Which is probably most art these days, though for different reasons.

Who is an emerging artist worthy of everyone’s attention?

At the moment, it’s the one I just met. In art and design, Rotterdam punches well above its weight, and since moving here a little over a year ago, I’ve been discovering new artists and designers constantly.

Aric Chen (right) with Tobias Wong. Courtesy of Aric Chen.

Who is an overlooked artist who hasn’t yet gotten their due?

My friend and occasional collaborator, the New York designer-artist Tobias Wong, who sadly passed away in 2010 at the age of 35. I’ve been thinking about him a lot lately, as the Museum of Vancouver opened a retrospective of his life and work [through July 23]. Tobi had an incredible wit; he was a genius at appropriation who questioned authorship, holding a mirror to our obsessions and desires in a kind of mash-up of Fluxus and Virgil Abloh, though he foreshadowed the latter by almost a decade. Both, of course, died too young.

What, in your estimation, is the most overrated thing in the art world?

The suspension of disbelief.

What is your most treasured possession?

My contact lenses. Life gets blurry without them.

What’s been your best investment?

If showing up is half the battle, it’s also probably the best investment you can make. I believe in serendipity, and the people I’ve met, the things I’ve seen and what I’ve been able to learn from it all have more often than not been the result of simply being there, wherever “there” is.

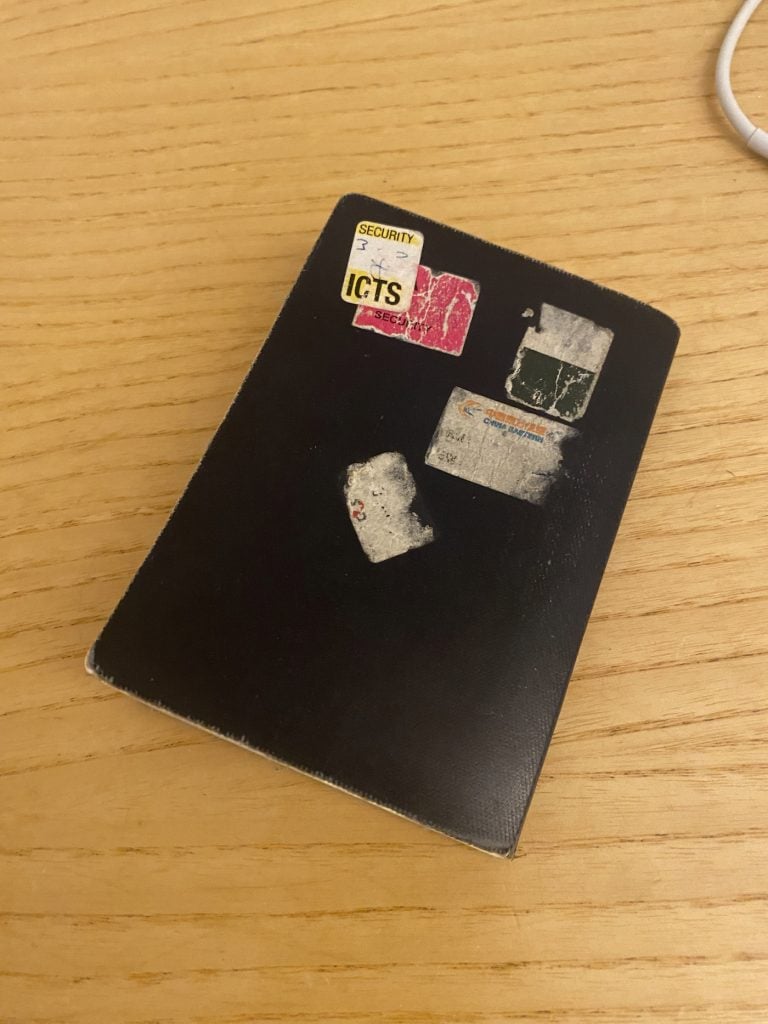

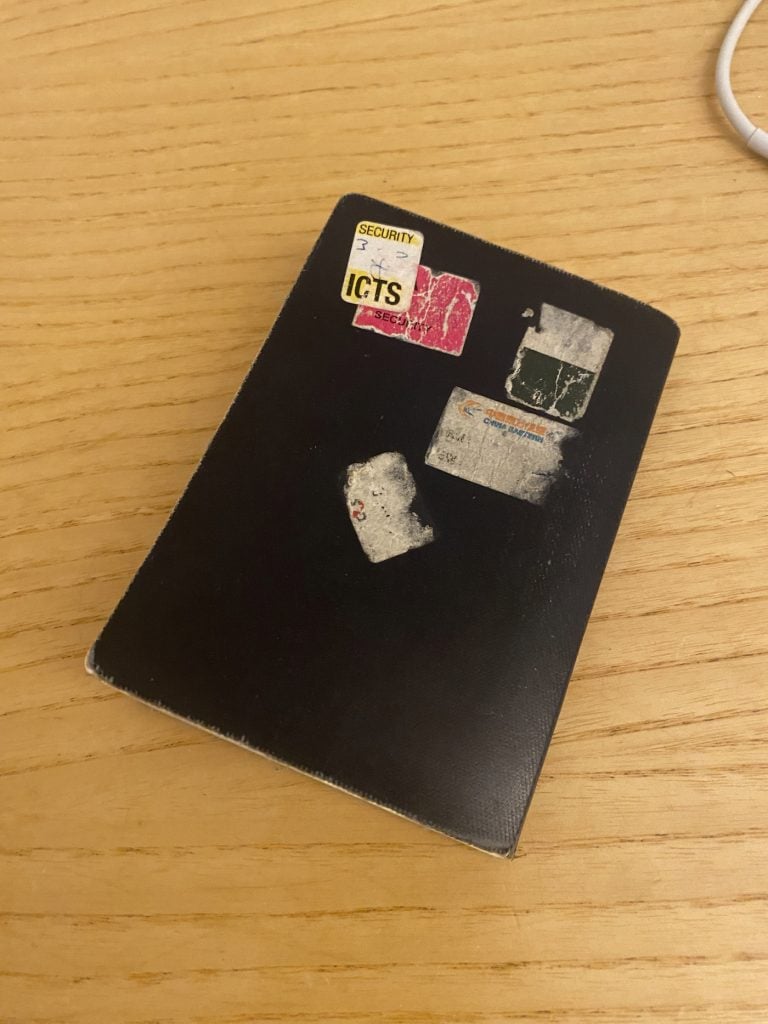

Aric Chen’s passport. Courtesy of Aric Chen.

What is something small that means the world to you?

Literally, my passport.

What’s not worth the hype?

By definition, anything that’s hyped is usually not worth the excitement. (Not to name names, though.) It’s better to keep things real.

What do you believe is a worthy cause?

This is an easy one: preventing the collapse of our planet. At this point, I don’t think I need to repeat all the “blah, blah, blah,” to quote Greta Thunberg, that’s often spoken about the issue. Let’s just say there are lots of things we have to do to address it. At the Nieuwe Instituut, we’ve developed, in collaboration with many others, an organizational model called the Zoöp. Basically, this is a framework that brings non-human interests and voices into an organization’s decision-making processes as a way of ensuring practices that are not just more sustainable, but regenerative. There’s a whole methodology to it. It’s been designed to be adaptable to all kinds of organizations, and earlier this year, we formally adopted this model to become the world’s first Zoöp. There are around 40 other organizations right now that are moving towards becoming Zoöps, so we’re off to a good start.

What do you aspire to?

I tend to take things one day at a time, so we might have to revisit this one later.

More Trending Stories:

Was Roy Lichtenstein an Appropriation Artist or Plagiarist? A New Documentary Probes the Ethics of His Multimillion-Dollar Comic Art Empire

The Dealer Who Sold the World’s Most Expensive Coin Has Been Arrested for Falsifying the $4.2 Million Artifact’s Provenance

What I Buy and Why: New York Collector Larry Warsh on His Early Eye for Basquiat, and the Octogenarian Artist He’s Coveting Now

87-Year-Old Artist Barbara Kasten on How Her New Career-Defining Monograph Shows She’s More Than Just a Photographer

Hito Steyerl on Why NFTs and A.I. Image Generators Are Really Just ‘Onboarding Tools’ for Tech Conglomerates

Art Industry News: Rishi Sunak Says There Are ‘No Plans’ to Return the Parthenon Sculptures to Greece + Other Stories

Is This Rolls-Royce the Most Extravagant Car Ever? Designed by Iris van Herpen, It’s Iridescent, Has a Signature Scent… and the Cosmos Inside

Generative Art Sensation Tyler Hobbs Has Filled His Debut London Show With Old-Fashioned Paintings—Painted by a Robot, That Is

The Final Sale of Masterworks From the Collection of Late Microsoft Founder Paul Allen Could Fetch $43 Million at Christie’s

A Wall Street Billionaire Shot Himself in His Family Office. His Death Is Reverberating in the Museum World, and the Art Market

Researchers in Vietnam Discovered That Two Deer Antlers Languishing in Museum Storage Are Actually 2,000-Year-Old Musical Instruments