People

On This Day in Art History: Van Gogh Cut Off His Ear

Scholars still debate the artist's motive.

Scholars still debate the artist's motive.

Eileen Kinsella

More than 125 years after the death of one of the most famous and beloved artists of all time—Vincent Van Gogh—interest and debate about the tortured genius has never been more intense. The past few months alone have seen several books, articles, museum exhibitions, and talks delving further into Van Gogh’s life in an attempt to better understand his oeuvre.

Of course, the artist will always be inextricably linked to a horrific act of self-mutilation that occurred on this day, December 23, in 1888, while he was living in Arles in the south of France. It is undeniably one of the most famous—if not the most famous—moments in art history.

In his book Breaking Van Gogh: Saint-Rémy, Forgery, and the $95 Million Fake at the Met, author James Ottar Grundvig writes of the night in question: “He stepped into the bathroom and stared at his maniacal, menacing, hyena-wild reflection, rubbed his stubbled neck, lifted the razor and, grabbing his left ear, sliced it off in a silent scream, locking eyes with his reflection in the mirror.”

Speculation about the incident, including what definitively prompted it and what happened in the aftermath, has, if anything, intensified in recent months. In an article titled “The Mysteries of Arles,” in the December issue of Apollo magazine, author Martin Bailey, who has just released a book about the artist, Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence, presents fresh material suggesting van Gogh was arrested in Arles on the “fateful night he severed his own ear.”

Additional information has came to light about the woman to whom Van Gogh actually gave the ear in Bernadette Murphy’s recently published book, Van Gogh’s Ear: The True Story.

“Why did Van Gogh cut off his ear and take it to a brothel?” writes Bailey in “The Mysteries of Arles.” “Behind this sensationalist query lies a more serious conundrum. What led such a creative artist to become so destructive?”

Bailey quotes Claude Monet, famous himself for his fantastical renderings of waterlilies, who once questioned: “How could a man who has loved flowers and light so much and has rendered them so well, how could he have managed to be so unhappy?”

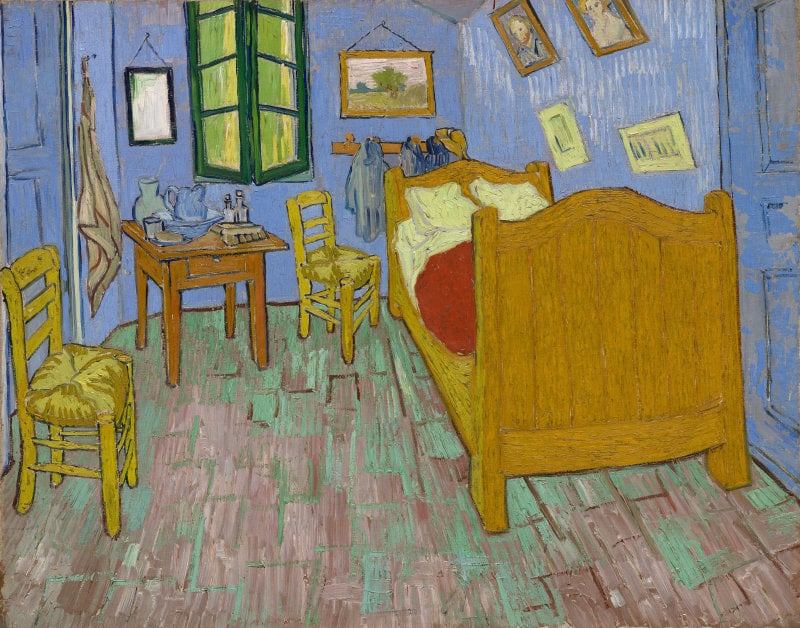

Vincent van Gogh, The Bedroom (1889). Photo courtesy Art Institute of Chicago.

As already has been well documented, Van Gogh performed the gruesome act after a particularly heated fight with fellow artist Paul Gauguin, with whom he was sharing the famous “yellow house” at the time. Gauguin claimed in his memoirs that Van Gogh had threatened him with a razor near the house before turning the instrument on himself.

Other speculation has centered on the fact that, earlier that day, Van Gogh received news of his brother Theo’s engagement to Johanna (Jo) Bonger after a whirlwind romance, and was deeply concerned it would affect Theo’s financial support, which was crucial to the artist (Bailey gives the most weight to this theory). Of course, the destructive act he was driven to commit may have been the culmination of several factors.

This past year, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam organized an exhibition delving into the artist’s mental illness, titled “On The Verge of Insanity: Van Gogh and His Illness”

Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of Dr. Gachet (1890). Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

As Bailey’s book was going to press, he discovered a 1933 article in a Dutch newspaper that he says has escaped the attention of specialists. The claim, in De Groene Amsterdammer, was based on an interview with Alphonse Robert, the policeman who had gone to the brothel and went on to become chief warden at the municipal hall. The article was written by a well regarded Van Gogh scholar named Benno Stokvis.

“In De Groene Amsterdammer, Robert recalls being on duty in what Van Gogh called ‘the street of the kind girls,’ the rue du Bout d’Arles. A prostitute summoned him to see her patronne. Madame Virginie Chabaud, who told him, ‘Look Monsieur Gogh who just departed from here left this for that girl.’ Inside the gruesome packet was a severed ear. Robert took it to his superior, who ordered two other policemen to help search for Van Gogh. They found him on his bed. Stokvis recounts: ‘Robert’s colleagues shortly afterwards arrested Vincent, and the doctor from the hospital, who had been warned in the meantime, had the painter transported to the Hospices Civils de la Ville d’Arles.”

Bailey admits that the reasons for Van Gogh’s arrest are unclear, but says the police may have regarded him as a threat to others, particularly since Gauguin had lodged a complaint after Van Gogh threatened him with a razor. However, he notes some have dismissed Gauguin’s claim as an effort to try to evade fault for being involved or responsible in part for Van Gogh’s gruesome act.

Murphy’s book helped Bailey identify the woman to whom Van Gogh gave the ear. Based on clues in Murphy’s book, “I named her as Gabrielle Berlatier,” says Bailey. For her part, Murphy says the woman was not a prostitute but a maid. “She was only 19 and prostitutes in legal premises had to be 21, although this law was not always observed. Whatever her status, Gabrielle was at the brothel at 11:30 pm when Van Gogh appeared,” Bailey writes.

In addition to the new Bailey and Murphy books, Abrams recently published Vincent Van Gogh: The Lost Arles Sketchbook, by highly respected scholar and Van Gogh expert Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, with a foreword by another well-known expert, Ronald Pickvance. The Van Gogh Museum has publicly challenged her findings, stating that it does not believe the sketchbook is the work of Van Gogh, prompting threats of legal action from the book’s French publisher Le Seuil.

We have also heard that artist and filmmaker Julian Schnabel—who was in attendance at a recent panel talk at the French Embassy’s Albertine bookstore in Manhattan—is working on a Van Gogh biopic.