On View

The 10 Absolute Best National Pavilions at the Venice Biennale

From Ghana's star-studded debut to Lithuania's delightful and chilling opera about climate change, here's what you won't want to miss.

From Ghana's star-studded debut to Lithuania's delightful and chilling opera about climate change, here's what you won't want to miss.

Artnet News

The Venice Biennale is often referred to as the art-world Olympics. Countries from around the world descend on the Italian city to show off the best contemporary art their country has to offer—and to compete to win the coveted Golden Lion for best national pavilion. Around 90 countries participated this year, a record high.

Because it’s impossible to see all 90, we’ve rounded up our favorites below. Here are the national pavilions not to miss.

Sun & Sea (Marina), Lithuania’s contribution to the 2019 Venice Biennale. Photo: Neon Realism.

Sun & Sea (Marina)

Artists: Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, and Lina Lapelytė

Curator: Lucia Pietroiusti

Location: Marina Militare, Calle de la Celestia, Castello, 30122

The premise of the Lithuanian Pavilion sounds gimmicky: It’s an opera about climate change set at the beach. In fact, it’s one of the most understated works of art about climate change I’ve ever seen—and that also makes it one of the most affecting. You watch it from a balcony, looking down at the familiar tableau of towels, beach chairs, and bright-colored bathing suits. The performers sprawl out across the beach and sing about their mundane vacations and minor annoyances. Slowly, it becomes clear that this sunny, sandy holiday masks the decay taking place offstage. Travelers tell stories of air travel interrupted by a volcanic eruption, a scuba diving trip to the milky white Great Barrier Reef, and a Christmastime spent in springlike weather. The production is haunting because unlike most art about climate change, it doesn’t attempt to knock you out with the gravity of the problem. Instead, it chills you by presenting a world not so different from your own—one in which you sit idly in the sun while everything around you rots.

—Julia Halperin

Still from Swinguerra (2019) by Barbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca at the Brazil Pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale.

Swinguerra

Artists: Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca

Curator: Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro

Location: Giardini

It’s pretty much impossible to see this pavilion without smiling. Artist duo Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca’s two-channel video installation (and accompanying photographs) bring you into the exuberant world of swingueira, a style of dance popular on the outskirts of Recife. (It looks to this non-expert eye as a mix of square dance, samba, and twerking.) The video, made in close collaboration with the dancers themselves, captures a regular practice session on an abandoned outdoor basketball court. The artists capture the dancers at work, on the sidelines, and filming each other on their phones, but also take us in and out of their individual music video fantasies. But it’s not all glitter and spandex. The name of the project, Swinguerra, combines the style of dance with the Portuguese word for war—a reference to the fact that these dancers (predominantly black and non-binary) are also at the center of an offscreen sociopolitical debate in Brazil, where some question whether their bodies, which move so freely onscreen, have the right even to exist.

—J.H.

Inci Eviner’s We, Elsewhere, Turkey’s contribution to the 2019 Venice Biennale. Photo: Julia Halperin.

We, Elsewhere

Artist: Inci Eviner

Curator: Zeynep Öz

Location: Arsenale

I won’t lie to you—I don’t really understand this pavilion. But it feels so thoroughly like stepping into the mind of an exceedingly creative person that I don’t really mind. Turkish artist Inci Eviner has created a multimedia funhouse. You walk up and down a series of ramps, into small chambers, and around corners to encounter strange videos projected onto the walls, wall drawings that look like hieroglyphics, and performers moving like contortionists through a forest of sculptures made from incomplete chairs. The indecipherable texts could contain the key to unlock the meaning of it all—if only you could understand the alphabet. Eviner is an artist who has developed and mastered her own aesthetic language across a wide variety of media. Her pavilion is like a fancy restaurant that serves pork three ways—each is distinct, and yet clearly the same animal. You leave feeling full and satisfied.

—J.H.

The installation by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye in the Ghana Pavillion at the Arsenale during the 58th Venice Biennale. (Photo by Luca Zanon/Awakening/Getty Images)

Ghana Freedom

Artists: Felicia Abban, John Akomfrah, El Anatsui, Ibrahim Mahama, Selasi Awusi Sosu, and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

Curator: Nana Oforiatta Ayim

Location: Arsenale

If the Venice Biennale offered an award for rookie of the year, the Ghana Pavilion would undoubtedly win it. Its new space—a series of curved, interlocking chambers designed by architect David Adjaye—houses an all-star lineup of work, including shimmering bottle-cap tapestries by sculptor El Anatsui, a sweeping video tracing West Africa’s violent history by John Akomfrah, and new portraits of imaginary subjects by painter Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. While most of these artists will be familiar to the international audience (and these works offer a chance to see them at their best), the exhibition also offers an opportunity for discovery. A video installation tracing Ghana’s abandoned glass factories by the little-known Selasi Awusi Sosuan gestures to the depth of contemporary talent coming out of the country, while gripping black-and-white portraits by Felicia Abban—considered Ghana’s first female professional photographer—offer a glimpse of an art historical canon in the process of recalibration.

—J.H.

Laure Prouvost, “Deep See Blue Surrounding You / Vois Ce Bleu Profond Te Fondre,” French Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale, 2019. © Giacomo Cosua.

Deep See Blue Surrounding You / Vois Ce Bleu Profond Te Fondre

Artist: Laure Prouvost

Curator: Martha Kirszenbaum

Location: Giardini

Beneath her phantasmagoric takeover of the French pavilion, Laure Prouvost is digging an illicit tunnel to the nearby British Pavilion, which is instantly appealing to those of us in the “fuck Brexit” camp. The artist, who has been selected to represent France but feels a greater connection to the UK, hasn’t asked permission to dig her tunnel (the biennale is notorious for its strict health and safety policies) but has been not-so-secretly doing it anyway under the cover of darkness. The action itself problemetizes the nationalist values implicit in an international event like the biennale, which is ultimately a competition with a shiny award for the winning country. The main event of the pavilion—which has resonated with audiences so much that in preview week it has had lines more than an hour long to access—is a new film that continues this thread of eliding the strict categories we employ to define ourselves. Its characters flip between English and French, often veering into nonsensical mistranslations, throwing into question some of the assumptions embedded within language itself. Visitors can watch the film from inside the confines of the squishy belly of an octopus, a boneless creature that can squeeze itself into tiny space—a metaphor for the fluidity of contemporary identity, which leans less and less on traditional categories.

—Naomi Rea

Exhibition view of the Estonia Pavilion. Photo by Andrej Vasilenko/CCA, Estonia.

Birth V – Hi and Bye

Artist: Kris Lemsalu

Curator: No official curator, but Lemsalu cites the “helping minds” of Andrew Berardini, Tamara Luuk, Irene Campolmi, and Sarah Lucas

Location: Giudecca island

Lemsalu’s ensemble of porcelain vulva fountains in an off-the-beaten path location is well worth the vaporetto ride to Giudecca island. The colorful sculptural installation, which feels like it has burst straight out of the primordial ooze, is an ode to the origin of life, birth, and self-invention. The work is situated in a working shipyard, and is accompanied by a shamanic soundscape by the New York artist Kyp Malone, sampling the various sounds of Venice. Vulvas surrounded by real eggs emerge out of clamshells, squirting and dripping sexuality, simultaneously recalling the act of conception and the painful expulsion from the womb. Supporting hands prop up a number secondary entities, which have sprouted legs and gained a sense of self that is projected to the outer world. One holds up a pair of basketballs (an athlete!), and another brandishes an accordion (a musician!), but the feedback mechanism of the fountain makes all the movements cyclical; like the mythical phoenix, these beings are birthed, grow, die, and rise again from their ashes.

—N.R.

Installation view of “Mondo Cane.” Courtesy and copyright of the artists and the Belgian Pavilion. Image: Nick Ash.

MONDO CANE

Artist: Jos de Gruyter and Harald Thys

Curator: Anne-Claire Schmitz

Location: Giardini

The Belgium pavilion’s creepy, mechanized puppets recall the animatronic figures that populate Disneyland’s problematic “It’s a Small World” ride; a series of characters meant to represent global cultures, which in reality present a very whitewashed version of diversity. The artist duo’s cast of white European characters—some of which have been thrown in jail, while others are trapped in a perpetual cycle of carrying out obsolete tasks—recall a fantasy ideal of an old Europe that never existed, which crops up more and more in the rhetoric and imagery deployed by the white nationalists advancing on the continent like a disease (although it’s not just Europe that is caught up in this fallacy). The show’s title, “Mondo Cane,” refers to a 1962 Italian film purporting to chronicle various weird and shocking cultural practices around the world, which was framed as a “documentary,” but was actually staged with exaggerated elements to enhance its shocking effect. On the walls are pastoral landscapes that increase this sense of nostalgia for a non-existent past, and the unsettling pavilion is a darkly humorous send-up of this false ideal.

—N.R.

Cathy Wilkes. Untitled (2019). Installation view, Cathy Wilkes, British Pavilion, Biennale Arte, Venice, 2019. Photo by Cristiano Corte ©British Council. Courtesy the Artist, The Modern Institute/Toby Webster Ltd, Glasgow and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels.

Untitled

Artist: Cathy Wilkes

Curator: Zoe Whitley

Location: Giardini

Throughout the opening week of the biennale there have been lines of people waiting to get a peek at Cathy Wilkes’s quiet installation. It is a testament to the art world’s trust in the tastes and capabilities of the UK’s contemporary art scene that Wilkes’ untitled, uncompromising, work has managed to secure the wayward attention spans of the biennale’s opening week. The work demands time and defies an easy reading because Wilkes refuses to digest her it for you. For nearly a decade, the artist hasn’t even given titles to her work, let alone offered the viewer any wall texts or prescriptive interpretations. She is not interested in obfuscatory curatorial jargon, or in offering a bite-sized précis of her work. Instead, she relinquishes control of her art to the viewer, which curator Zoe Whitley deems an “incredibly generous and selfless” act.

—N.R.

Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz, Moving Backwards, Swiss Pavilion at the 58th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia, 2019. Photo by Annik Wetter, courtesy the artists.

Moving Backwards

Artists: Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz

Curator: Charlotte Laubard

Location: Giardini

One of several countries with a line out the door during the biennale preview, Switzerland has turned its pavilion into a darkened night club, with a sequined curtain opening to reveal Moving Backwards, a film by Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz. The camera pans across five dancers performing post-modern choreography involving experimental backwards movements, occasionally interrupted by a curtain. The duo, who has been collaborating since 2007, is responding to what they see as an alarming international trend toward conservatism, and how that has negatively impacted the queer community. Faced with a society that appears to be bent on erasing societal gains, Boudry and Lorenz were inspired by Kurdish women guerrilla fighters, who deceived their enemies about their movements by wearing their shoes backward as they walked through the snowy mountains. Seamlessly mixing actual backwards motions with digitally reversed footage, Moving Backwards echoes that confusion, suggesting there can be creative means of resistance toward the end of progress.

—Sarah Cascone

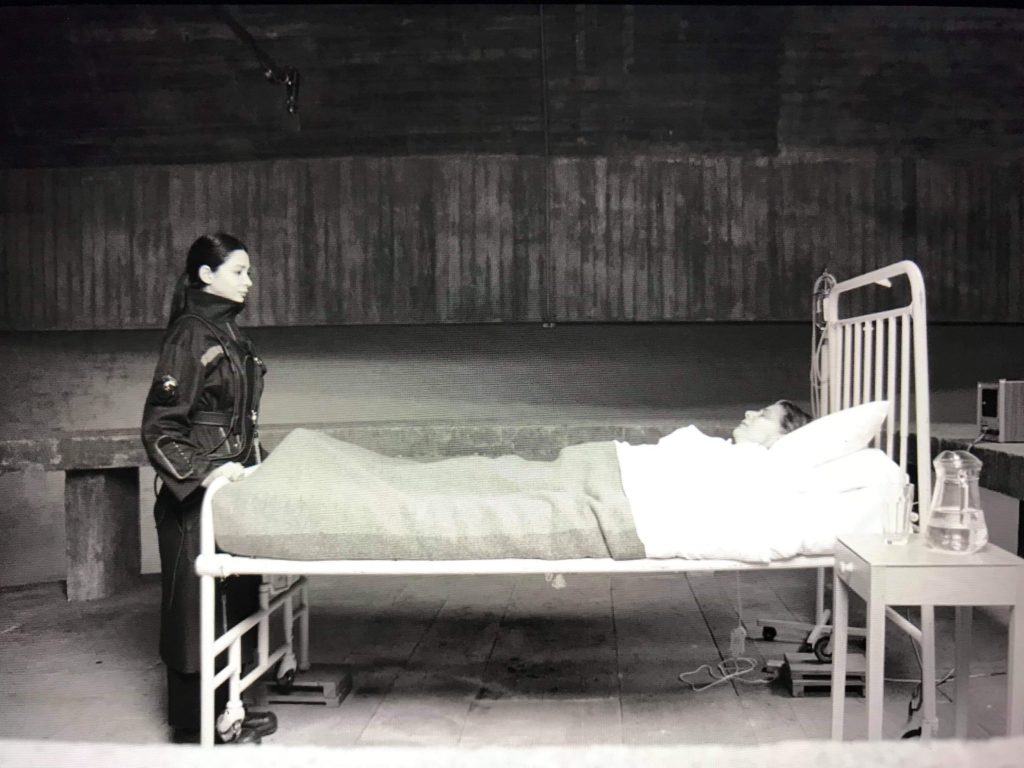

Larissa Sansour, In Vitro, film still, (2019). Directed by Søren Lind. Photo by Lenka Rayn H.

Heirloom

Artists: Larissa Sansour

Curator: Nat Muller

Location: Giardini

Half of the Danish pavilion is a theater where audiences can sit and watch Larissa Sansour’s black-and-white science fiction film, In Vitro. On the other side of the building, an imposing, monumental black disc stands in a darkened room. The piece, titled A Monument for Lost Time, is featured in the two-channel video, with the protagonist in the post-apocalyptic tale gazing up at its mysterious expanse. She’s grown up underground, beneath the city of Bethlehem, and has never seen the sun. Now, she stands poised to take a leadership role in her community, which survives by tending an underground orchard. The founder, now an old woman, escaped the ecological disaster that left the surface uninhabitable, but now sits on her deathbed. What could read as a simple morality play, warning of the dangers of climate change, becomes something more—a rumination on fact, fiction, and identity. The conversation between the two characters is intense, weighed down by the fight for the survival of the human race. Raised in an enclosed environment, the young women questions her readiness to lead, resentful that so much of her knowledge is secondhand, based on the memories of those who remember life before the disaster. Her existential doubt is exacerbated by her strange circumstances. But as her predecessor sagely reminds her, “we are all raised on nostalgia, our own experiences blended we others’ we are told.”

—S.C.