Archaeology & History

You Can Win $250,000 If You’re Able to Assist This Super-Powered A.I. in Deciphering Ancient, Damaged Scrolls

The scrolls were discovered in 1752, but fire damage made them too fragile to unroll.

The scrolls were discovered in 1752, but fire damage made them too fragile to unroll.

Sarah Cascone

Thanks to artificial intelligence, scientists are finally able to read a cache of scrolls incinerated during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the year 79—but to decipher the entirety of the manuscripts, a team led by University of Kentucky computer scientist Brent Seales is offering $250,000 to anyone who can help complete the arduous task.

Seales is the lead researcher on a project that has developed an A.I. system powered by a machine-learning algorithm trained to identify ink on the charred scrolls. Using high-resolution X-ray images of the documents, the A.I. can spot written letters and symbols on the fire-damaged texts without attempting to open the fragile scrolls.

For the Vesuvius Challenge contest, participants will have access not only to the 3-D X-ray images of the scrolls, but also to the A.I. software that holds the key to extracting their secrets. Sharing the technology Seales’s team has built will help them scale up the task of extracting the hidden layers of text from these writings.

“We’ve shown how to read the ink of Herculaneum,” Seales told the Guardian. “That gives us the opportunity to reveal 50, 70, maybe 80 percent of the entire collection. We’ve built the boat. Now we want everybody to get on and sail it with us.”

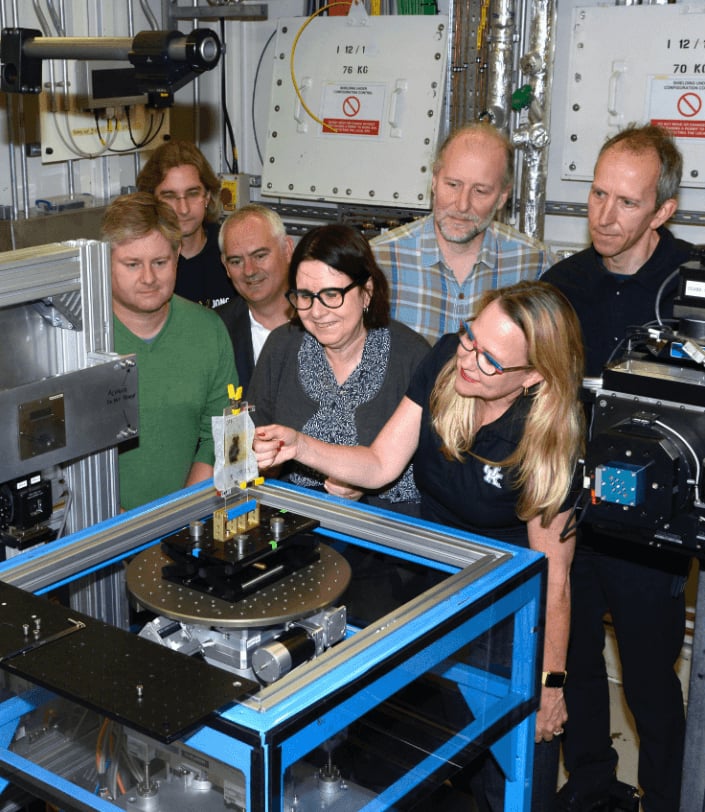

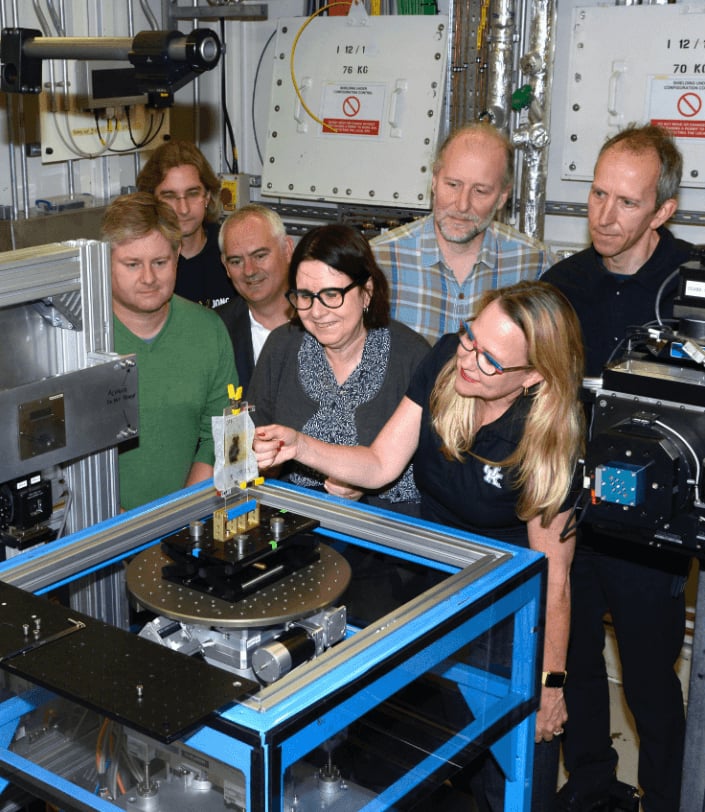

Brent Seales, director of the Digital Restoration Initiative at the University of Kentucky, examines a piece of Herculaneum scroll that was scanned at Diamond Light Source in Didcot, west of London. Photo by Geoff Caddick/AFP via Getty Images.

Archaeologists recovered the charred remains of the ancient library of Epicurean philosophical texts in 1752, from the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum, near the Bay of Naples. (The home, thought to have belonged to Julius Caesar’s father-in-law, Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, is the inspiration for the Getty Villa in Malibu.)

For centuries, the contents of the scrolls have remained a mystery, because unfurling the fragile documents would have destroyed them.

A 2,000-year-old Herculaneum scroll. Photo by the Digital Restoration Initiative.

Now, if all goes according to plan, people will have a chance to read these carbonized Greek texts—some may also be written in Latin—for the first time since the fateful eruption that buried Pompeii.

Scientists have previously made similar breakthroughs such as employing algorithms to read 300-year-old, delicately folded letters with paper locks. (They’ve also used CT scans to digitally unwrap an ancient mummy.)

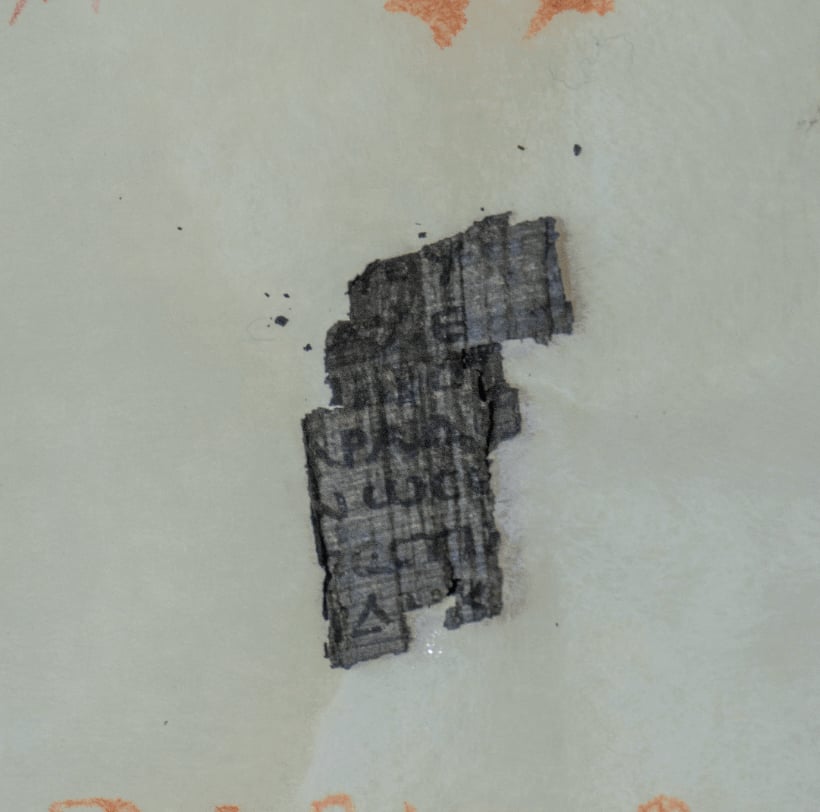

A papyrus fragment from the collection of the Institute de France. Photo by the Vesuvius Challenge.

With the Herculaneum library, scientists have already identified Greek letters and symbols on the scrolls using infrared imagery, and begun deciphering the text. The contest is focusing on two intact scrolls from the Institut de France,. For training purposes, entrants can also analyze images of three tiny papyrus fragment where the ink is already visible.

There are 14,000 ultra-high-res .tif images of both scrolls—each individual centimeter is captured in about 1,250 scans. Researchers took all the scans using a Diamond Light Source particle accelerator, at a resolution of 8µm (micrometers).

A view of the ruins of Herculaneum, in background the Mount Vesuvius in Herculaneum, Italy in March, 2003. Photo by Eric Vandeville/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

To win the $150,000 prize, all you have to do is be the first to read the four passages of text in the scrolls. The contest runs through the end of the year, and also offers an additional $100,000 for detecting ink on the 3-D scans.

“A human cannot pick this out with their eye,” Seales said. “The ink fills in the gaps that otherwise create a waffle-like pattern of the papyrus fibers. That pattern gets coated and filled in and I think that subtle change is what’s being learned.”

See a video of one of the scroll scans below.