Law & Politics

Liberal and Conservative Justices Seem Split in the Supreme Court’s Landmark Andy Warhol Copyright Case (and Not in the Way You May Think)

The case is expected to have major ramifications for the future of creative freedom.

The case is expected to have major ramifications for the future of creative freedom.

Sarah Cascone

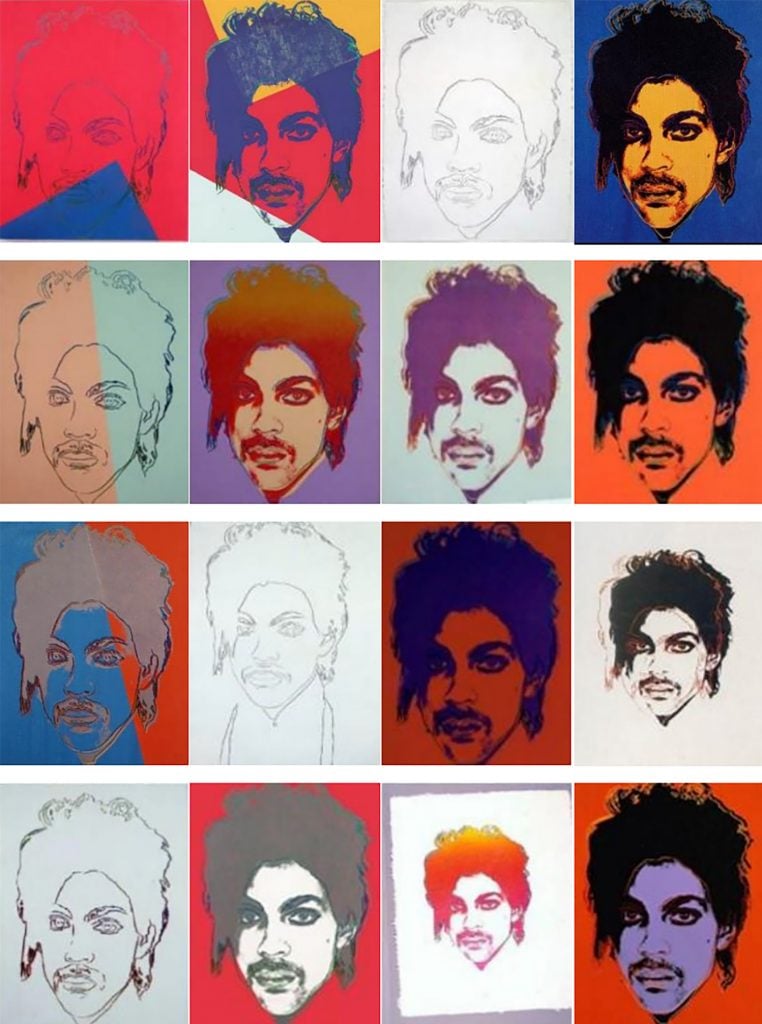

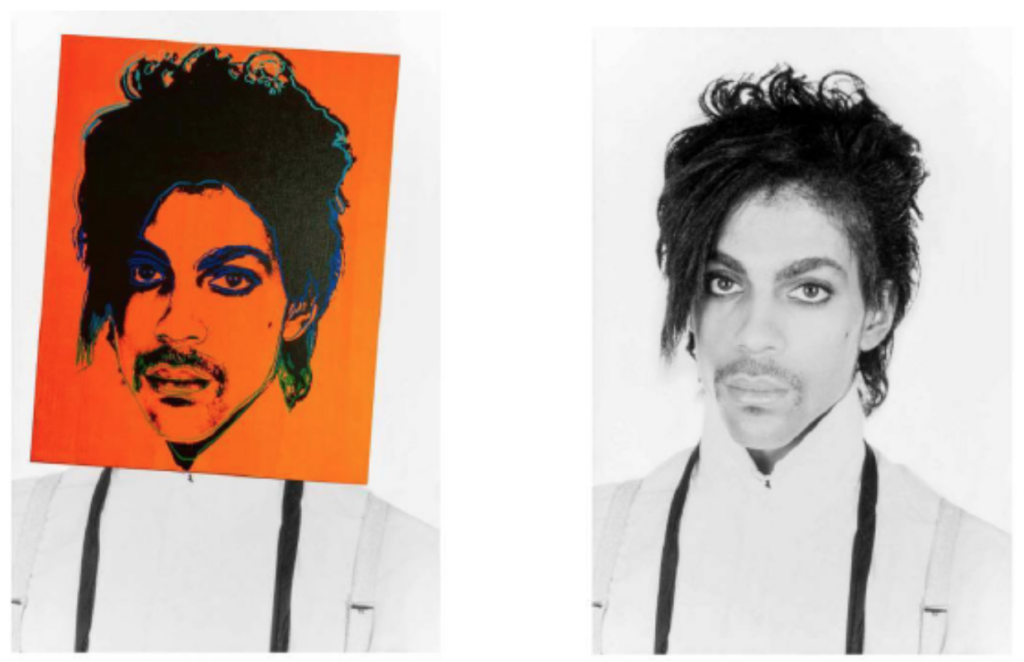

For close to two hours yesterday, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s lawsuit against the Andy Warhol Foundation over the late Pop artist’s use of her 1981 portrait of the musician Prince in a series of 16 screenprints in 1984.

At stake is the future of both copyright and creative freedom, with both sides making impassioned cases during the debate.

Roman Martinez of the firm Latham and Watkins, which is representing the Warhol Foundation, argued that Andy Warhol transformed the purpose and character of Goldsmith’s original image, taken in and imbued it with a new meaning and message—one of the four factors in determining fair use under the Copyright Act.

A ruling for Goldsmith could “have dramatic spillover consequences not just for the Prince series, but for all sorts of works of modern art that incorporate preexisting images and use preexisting images as raw material in generating completely new creative expression by follow-on artists,” Martinez said.

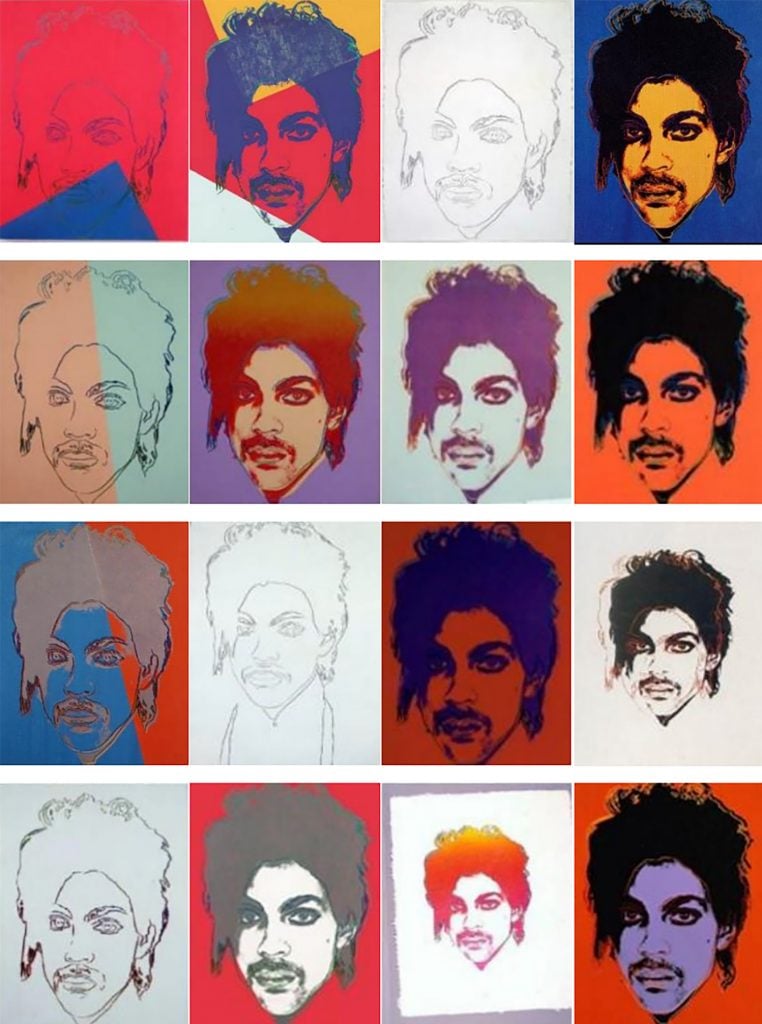

Lynn Goldsmith’s 1981 photo of Prince was the basis for an Andy Warhol screen print. Courtesy of the court filing.

Goldsmith’s lawyer, Lisa Schiavo Blatt of Williams and Connolly, fired back that that test “would decimate the art of photography by destroying the incentive to create the art in the first place. She warned that “copyrights will be at the mercy of copycats,” and that anyone could then create an unlicensed spinoff or sequel to an existing work.

The dispute started in 2017, after Goldsmith spotted Warhol’s Orange Prince on the cover of a special Condé Nast memorializing the recently deceased musician. Vanity Fair magazine had paid her $400 in 1984 to license her previously unpublished Prince photograph, shot in 1981 on assignment for Newsweek, to create the Warhol illustration.

In the new publication, Goldsmith wasn’t credited as the photographer—and, unlike the Warhol Foundation, which charged the magazine a $10,000 fee for the image—she wasn’t paid. When she reached out to the foundation, it responded with a preemptive lawsuit asking the court to declare Warhol’s portrait fair use; Goldsmith responded in kind.

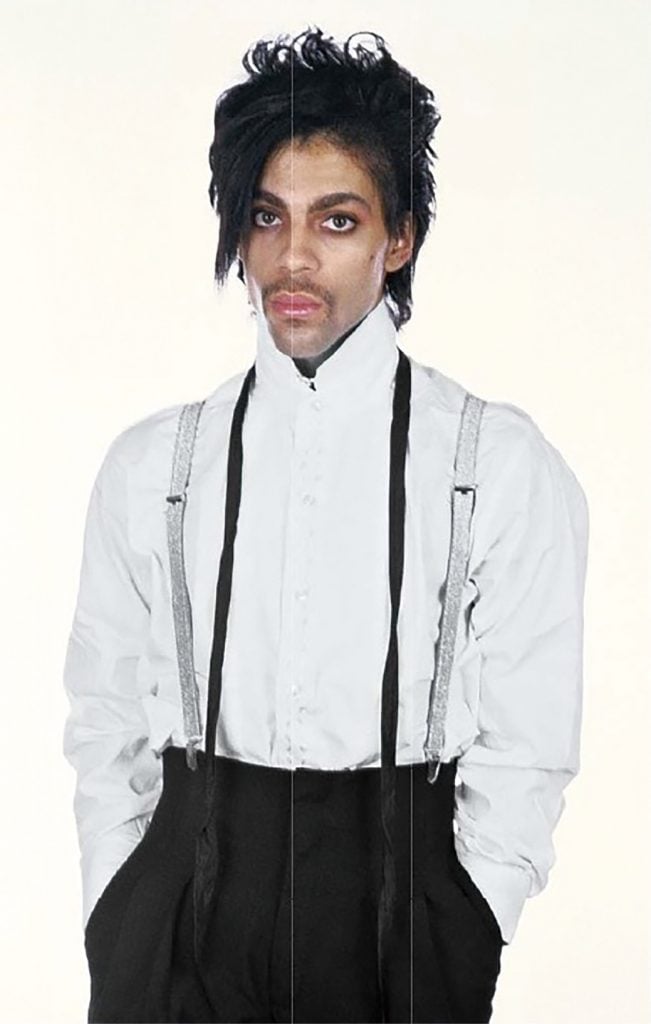

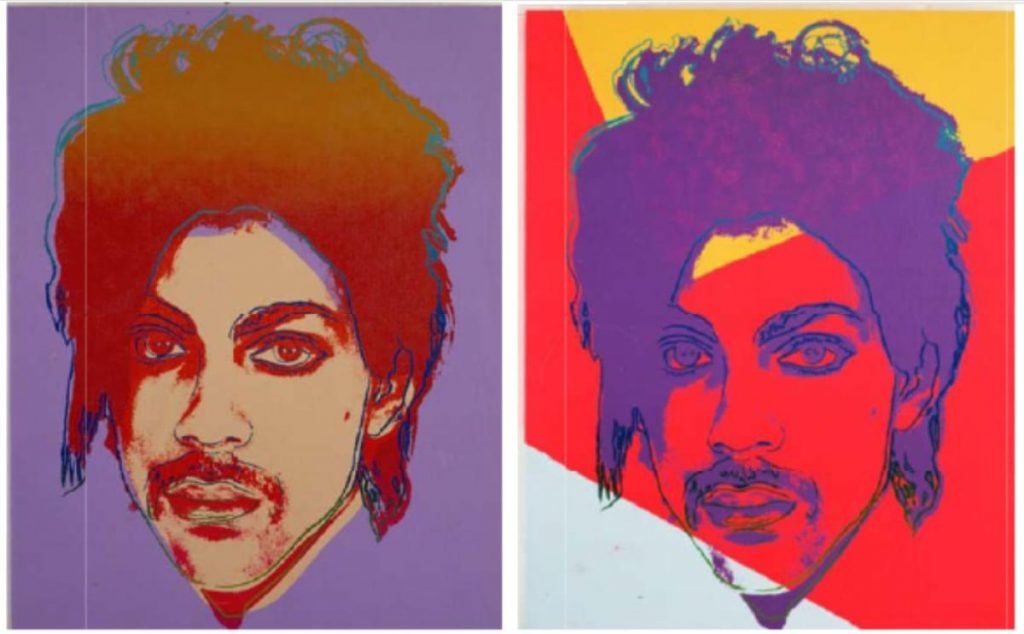

Andy Warhol, Prince (ca 1984). The artwork was based on a Lynn Goldsmith photo, and the Second Circuit ruled it was not fair use. The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The Supreme Court is currently reviewing a 2021 ruling from the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals in favor of Goldsmith, which had overturned a New York’s federal judge’s finding in 2019 that Warhol’s Prince series was fair use.

The 2019 judge found that Warhol had transformed Goldsmith’s original portrait, which presented a “vulnerable, uncomfortable person,” into “an iconic, larger-than-life figure.” But the court of appeals countered that a “judge should not assume the role of art critic” or try to pin down a work’s meaning—both works served the same purpose as depictions of Prince, so Warhol’s pieces weren’t transformative.

Goldsmith’s case also argues that to be fair use, “you have to justify the copying, not just explain why your work is a creative addition to the world of creative additions,” Blatt said.

The question being considered by the Supreme Court is fairly narrow: whether or not changing the source material’s meaning makes a work transformative, and thus fair use. Moreover, is it the place of the court to try to access a work’s meaning—and is that meaning just based on an artist’s original intentions, or how it is perceived by audiences?

Andy Warhol’s Prince portrait overlaid on top of the original Lynn Goldsmith photograph of the musician, as reproduced in court documents.

“There’s no real dispute in this case that the meaning or message of the two works were different,” Martinez said in the hearing. “The only real question in this case is whether that difference matters.”

In making its decision, the court has two major legal precedents to consider: its rulings in the 1994 case Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, and the 2021 case Google LLC v. Oracle America. (There were also a lot of references, separately, to Warhol’s famous “Campbell Soup Can” works.)

Both cases were found to be fair use: the former for 2 Live Crew’s parody cover of Roy Orbison’s “Pretty Woman,” the latter for Google’s use of 11,330 lines of computer code from Java in the Android operating system.

Newly appointed Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson was concerned that the Warhol Foundation’s argument conflated a work’s message or meaning with its purpose. Did the two Prince images share the same purpose—that is, to present a depiction of Prince, or did the meaning behind the two portraits change that purpose?

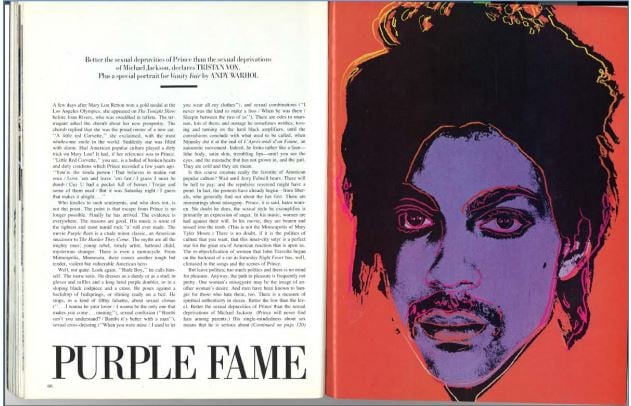

Martinez argued that it did, and that a photorealistic portrait like Goldsmith’s and an illustration like Warhol’s were not interchangeable, and would not be used by the same types of publications. He also pointed to the title of the article for which the Warhol illustration was originally commissioned, “Purple Fame.”

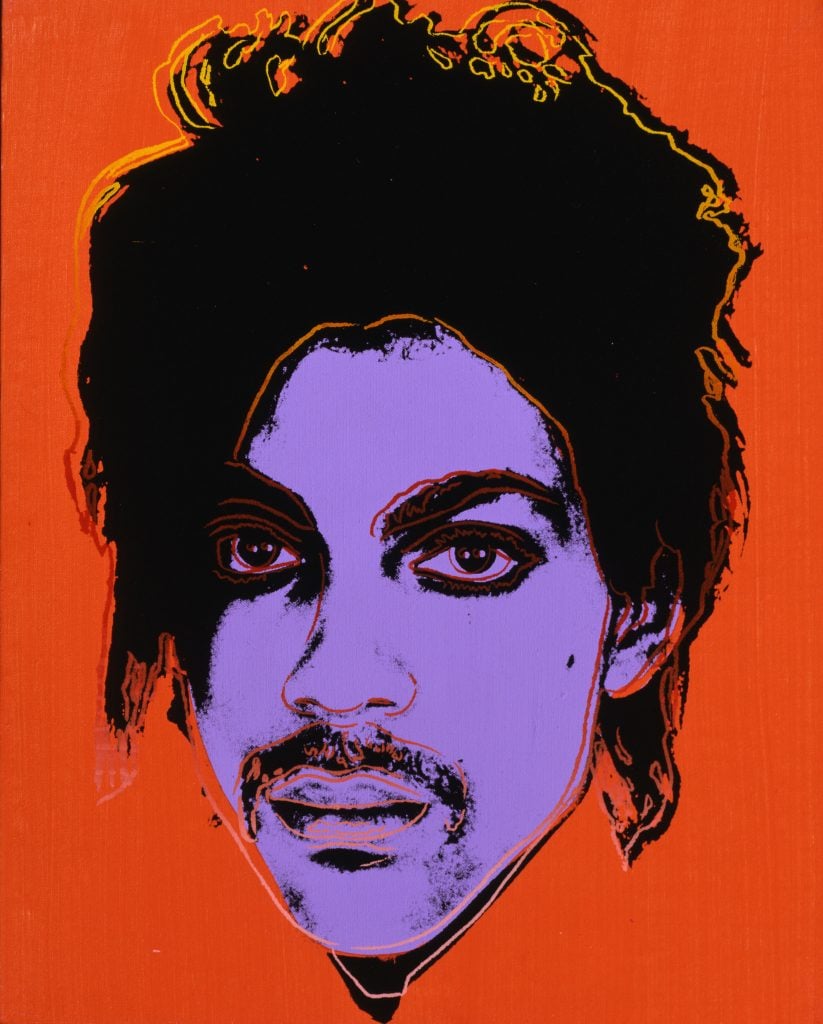

The 1984 Vanity Fair article as reproduced in court documents.

“It’s perfectly natural to illustrate that article that you would want a Warhol-type work that has as its meaning or message—a picture of Prince that shows him as the exemplar of sort of the dehumanizing effects of celebrity culture in America,” he said.

It was an argument that seemed to sway Chief Justice John Roberts, who mused that “you don’t say, ‘Oh, here are two pictures of Prince.’ You say, ‘that’s a picture of Prince, and this is a work of art sending a message about modern society.’”

But Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted that it was “hard to see” how the Warhol portrait didn’t compete with Goldsmith’s: “They both sell photographs to magazines.”

Justice Elena Kagan was also more skeptical, wondering if Warhol’s fame and instantly identifiability makes it easier to ascribe a new message to his works.

“If you imagine Andy Warhol as a struggling young artist, who we didn’t know anything about, and then you look at these two images,” she said, “you might be tempted to say something like, well, ‘I don’t get it. All he did was take somebody else’s photograph and put some color into it.’”

Blatt agreed, noting that “fame is not a ticket to trample other artists’ copyrights.”

Martinez countered that a ruling in favor the foundation of will actually help any emerging artist “who wants to create new and innovative work that integrates preexisting images”—and that limiting the scope of fair use will “chill the creation of new art by established and up-and-coming artists alike.”

He asked the court to consider whether the Warhol Prince image represents the kind of transformative use that “copyright laws are intended to foster, which is really encouraging follow-on artists to use creativity to kind of introduce new ideas into the public domain.”

Two of Andy Warhol’s Prince portraits. Courtesy of court documents.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett asked whether the question of fair use for the Prince series would differ if the work was hanging in a museum, rather than being reproduced in a magazine.

“Goldsmith doesn’t compete in that market… I don’t see how any museum can’t display these,” Blatt allowed. “What’s not protected is just the commercial licensing.”

It was a concession that might hurt Goldsmith’s case.

“[Museums] show Andy Warhol because he was a transformative artist because he took a bunch of photographs and he made them mean something completely different,” Kagan pointed out.

But the decision may ultimately hinge on the fact that the Warhol Foundation licensed the image for reproduction in Vanity Fair.

“Campbell’s soup seems to be an easy case. The purpose of the use for Andy Warhol was not to sell tomato soup in a supermarket. It was to induce a reaction from a viewer in a museum or in other settings,” Justice Neil Gorsuch said. “The difficulty of this case is that this particular image is being used arguably, maybe, for the same purpose, to identify an individual in a magazine.”

The debate meandered over the course of close to two hours, touching on such wide-ranging references as the Lord of the Rings, All in the Family, and the Mona Lisa. At one point, Justice Clarence Thomas even revealed that he was a Prince fan in the ’80s, prompting laughter in the courtroom.

A decision from the court is expected sometime in the coming months.