People

The Disturbing Paintings of Werner Büttner, Forgotten Bad Boy of German Art, Are Starting to Look Alarmingly Good. The Market Has Noticed

The German painter recently opened a career-spanning solo exhibition in Berlin.

The German painter recently opened a career-spanning solo exhibition in Berlin.

Kate Brown

Standing in a small gallery in Cologne, painters Werner Büttner, Albert Oehlen, and Martin Kippenberger broke out into song. Sporting wool suits and mops of dark hair, they barreled out a German miner’s hymn, taking cheeky pleasure in alienating the room around them while making themselves the center of it. It’s 1983: Cologne is the beating capital of the West German art world, and this trio of artists is bent on basking in its spotlight.

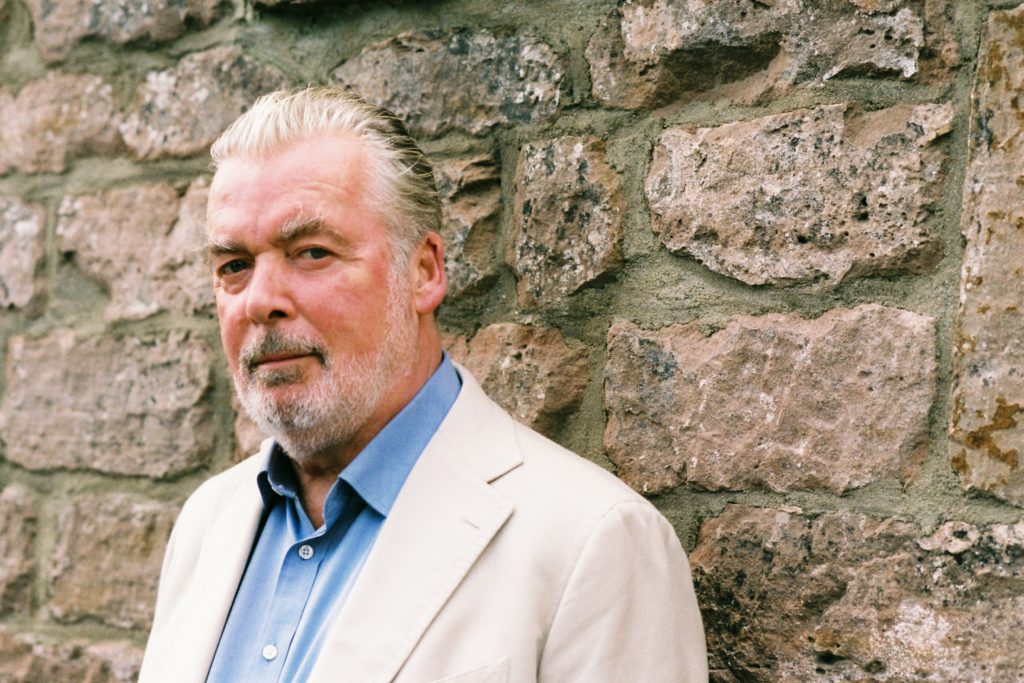

Decades later, Büttner still remembers the evening well. Without prompting, he belts out a few lines of the hymn to me, pounding his fist in the air, while we tour his current solo exhibition at Contemporary Fine Arts in Berlin. He holds a cigarette in one hand and an ashtray in the other while I follow him around a career-spanning survey that reaches back to 1979. Our conversation inevitably ebbs and flows back towards those incubation years alongside Oehlen and the late Kippenberger.

“It annoyed people, but it kept a lot of idiots away from us,” recalls Büttner of the trio’s penchant for singing in public. “We were called communists, anarchists, fascists, male chauvinists. We got it all.” People may have been irritated, but many others were jealous and impressed by this inner core of artists (Georg Herold deserves honorable mention here, as does Albert’s brother, Markus Oehlen). Büttner was one of the few former East Germans in the group, who were dubbed the “enfants terribles” or “bad boys,” and later enshrined among the ranks of the Junge Wilde, a post-war art movement that stood in opposition to Minimalist and Conceptual art, balking against authority in general. By today’s standards, such a male-dominated movement seems outmoded. But we shouldn’t underestimate the role that Büttner and his cohort played in transforming the postwar art scene and fast-forwarding the progress of contemporary painting.

By some stroke of market magic in the mid-2000s, both Oehlen’s and Kippenberger’s prices soared, following a slow and steady climb through the ’90s. And while Büttner’s influence on representational painting has remained self-evident to the German art world, it’s still less commonly celebrated on fair floors and auction blocks worldwide. While his old friends Oehlen and Kippenberger (who died in 1997) have enthralled the English-language market and its museums over the last decade with their shapeshifting paintings and sculptures, Büttner has carried on a bit more quietly—but he’s still as irreverent as he ever was, successfully selling his work to collectors who well-understand his relevance and staying power.

Martin Kippenberger, Werner Büttner, Albert Oehlen at the exhibition “Women in the life of my father” at Galerie Erhard Klein in Bonn in 1983. Photo: Franz Fischer / ZADIK Central Archive for German and international art market research, Cologne (ZADIK).

Forty years on, Büttner’s dressed in a crisp wool suit, still faithfully following his chosen path. What has changed is that the very subject matter and style he has long embraced—a dark humor in the face of disillusionment, and a subversion of classical art and the pastoral—has gained a foothold in the wider art world. The stylized bravado of rising stars like Jana Euler, or the dark cynicism of emerging talent like Mathieu Malouf, underscore how a new era of in-your-face painting has returned.

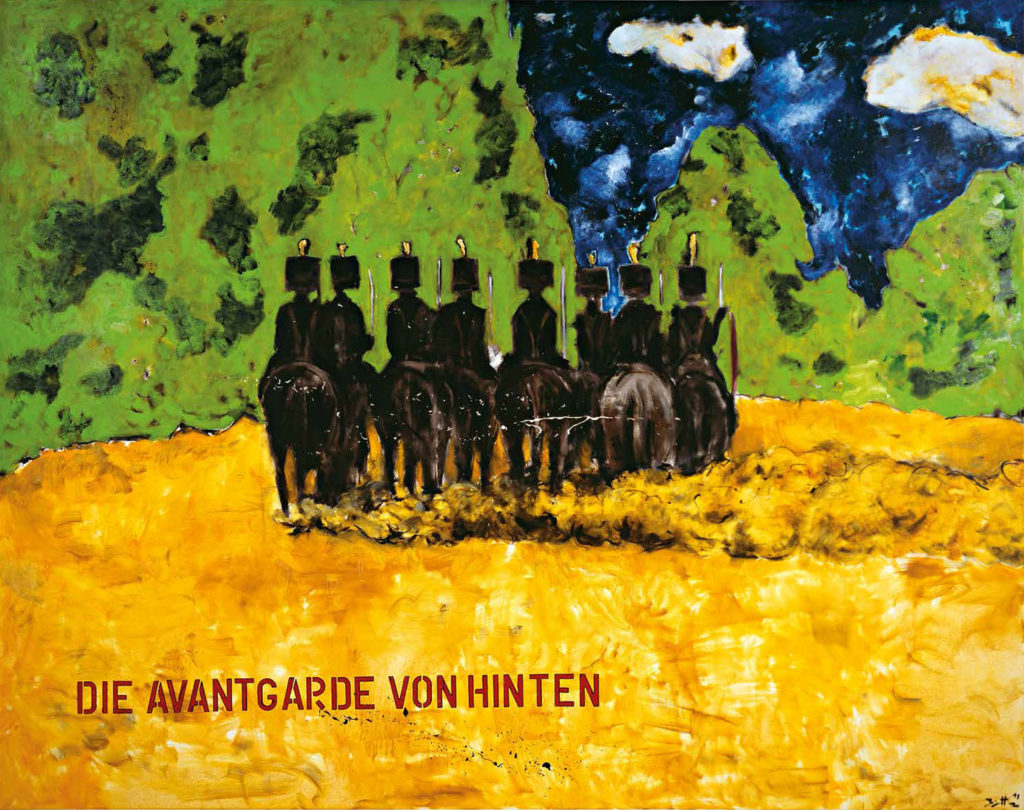

While many in his 1980s scene made vivaciously colorful works, Büttner has always stayed in the realm of natural ochres and earth tones. He cites cavemen as his colleagues. When he uses bright colors, which he tends to do more these days, they still seem a bit acrid. As always, he fills up the canvases in a heavy painting style called pastose (a skill he’s refined, apparently, since his days as a young “smearer,” he tells me).

He laughs and cheekily suggests his career would have taken off differently if he used colors that looked better above sofas. Certain subject matter, too, may have scared off the occasional collector. In one self-portrait from 1981 that is on view at Contemporary Fine Arts, a seated Büttner stares out at the viewer, his jaw cocked to the side. Look down, and you’ll see that he’s masturbating through a paper bag (for the record, such public behavior is not something he was ever in the habit of actually doing). The painting is funny, contrarian, and a bit lonely.

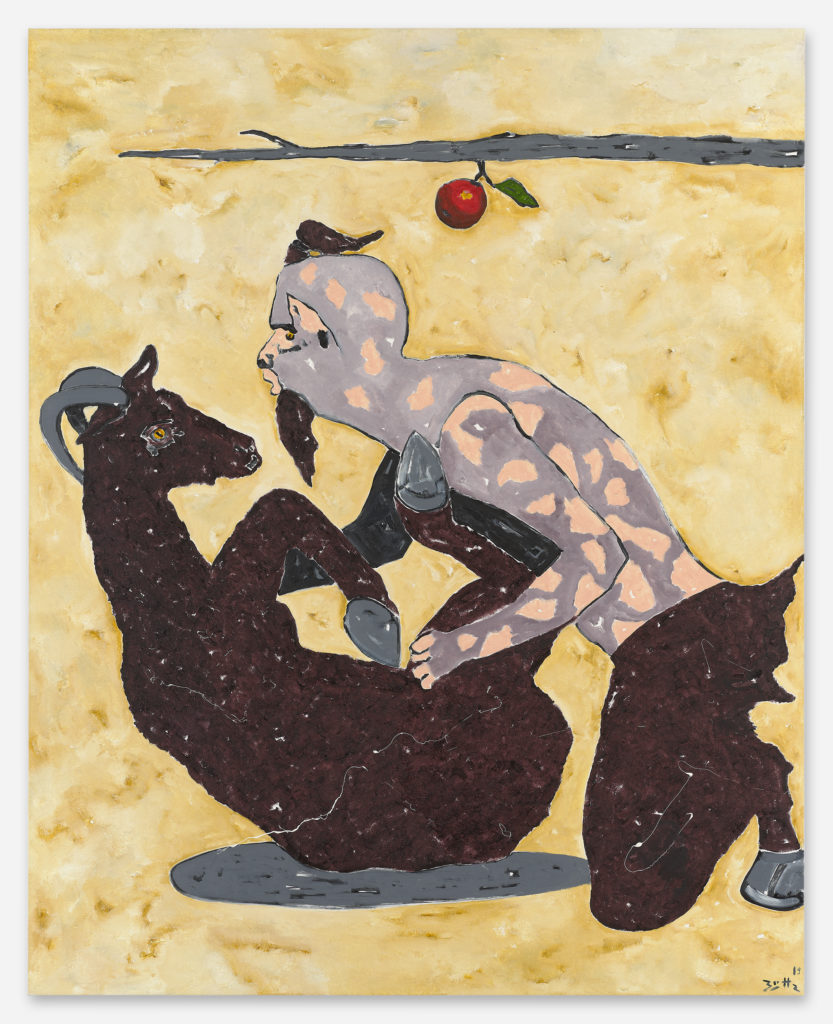

Recent works from 2019 do show a more subdued version of the typically raucous Büttner. The content and trajectory has changed but the mood is unflinchingly the same. Artnet News columnist Kenny Schachter, one of his many longtime fans, advises: “Don’t let appearances mislead you—through all the cynicism and scorn, Büttner is as much of a painting prude in love with the medium (and its past) as an unruly anarchist trying to upend it all.”

Werner Büttner, Die Avantgarde von hinten [The avant-garde from behind], (2011). Courtesy the artist and Marlborough, New York and London.

Marlborough began working with Büttner about five years ago, and has shown four solo exhibitions between their London and New York spaces; the gallery says that the demand has been rising. Paintings from the late 1970s and 1980s, understandably rarer to come by, tend to range from $100,000 to $500,000 for the largest pieces, while newer paintings hover between $75,000 and $180,000. At Contemporary Fine Arts, which showed a diverse group of works from the early years and four new paintings from 2019, prices were between €54,000 and €250,000 ($60,000 and $276,000). That’s not quite in the realm of his more famous peers; Oehlen’s work is projected to command prices above $10 million in the near-future. Works from Kippenberger’s estate now command prices upwards of $10 million. But Büttner’s not thinking about the market.

“There is a fascination for big sums and the media is on it but, in the end, you don’t have to think about that, and that is healthier,” the artist says. “Or, you keep out of the game.” He notes that he has every comfort in life. He does what he loves. He lives in a castle outside of Hamburg, drives a Tesla, and has what he calls “the kind of freedom you can get in this world.” He seems content. “I let it lands the way it lands,” he adds.

Werner Büttner, Pan, Penetrator der Obstdiebe, und Spielkameradin (Pan, Penetratot of Fruit Thieves, with Playmate) (2019). Courtesy Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin.

Marlborough is helping to shape a new trajectory for Büttner. “There have not been the sorts of exhibitions that [would] make him a household name, but that is changing now,” says Max Levai, Marlborough’s president, speaking over the phone from New York. The anglophone gallery has certainly played a key role in bringing Büttner to foreign audiences. A show is in the works for 2021 that will capture the larger span of his career, honing in on the early years.

“What people are trying to achieve in representational painting today is this aptitude and fluency that Werner has,” says Levai. “There is a renewed interest in this late 1970s and 1980s moment in Cologne and Werner was really an an architect of it. He’s been dedicated to a specific attitude in painting since day one and there is a beautiful linear progression to his work.”

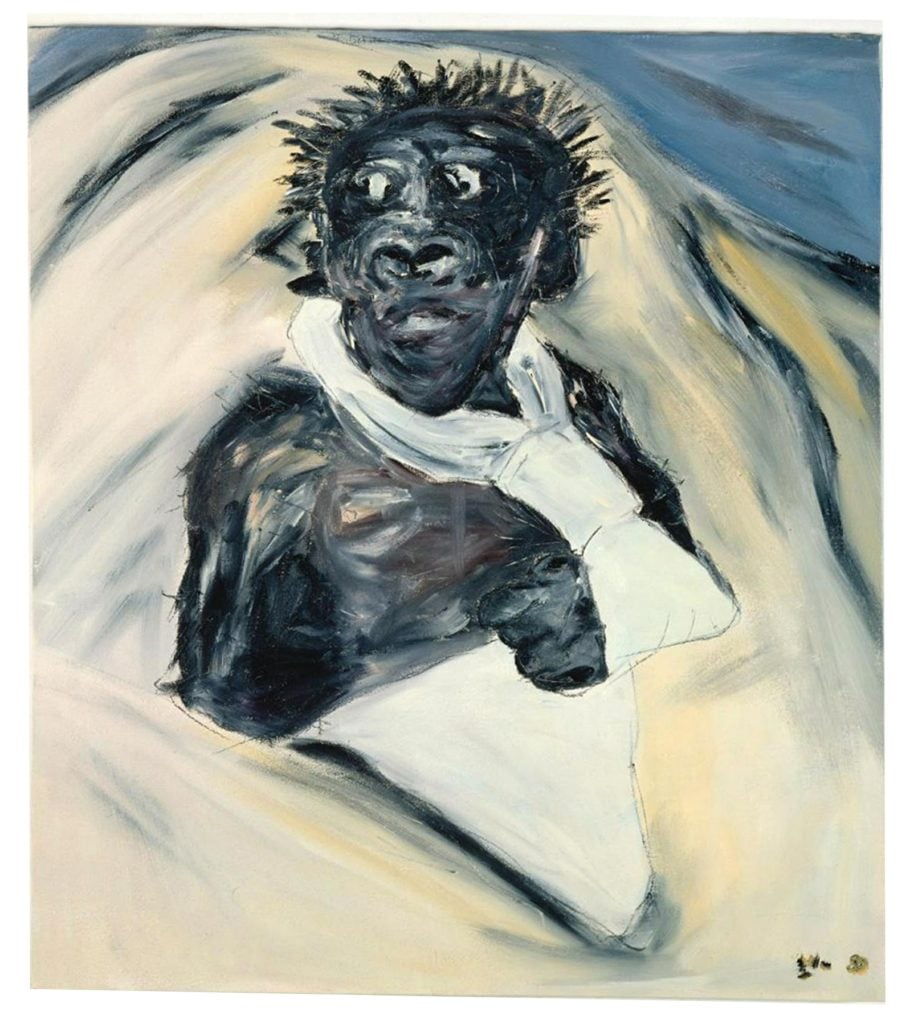

Werner Büttner Socialstaatsimpression (1980). Courtesy Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin.

“Art for art’s sake never interested me. After World War II, I had the impression that every artist who wanted to be cool said that art is art, and everything else is everything else. I never believed that,” says Büttner. He’s 65 years old now and, when not teaching at Hamburg’s University of Fine Arts (where he helped steer the practices of Jonathan Meese and Daniel Richter, two former students), he retreats to his castle home and studio, a refurbished, historic hotel he bought some years ago. “Art has to have something to do with reality, with what is happening on this fucking planet,” he adds. “If it doesn’t, for me it is boring.”

Many of the works are as funny as they are tragic and disturbing, and true as they are preposterous. While he certainly paints about painting (he is a painter’s painter, through and through), Büttner’s work also has two feet kicking topical issues. In one work, the chair backs of an empty cinema are depicted above the question, “Why Not Die Out?” In another sardonic painting, a plain-looking house hangs precariously on the edge of a cliff, while the figure of Jesus hovers nearby (“Christ Attempts Visit,” as the title enigmatically explains).

Installation view of Werner Büttner, “Poor Souls” at Marlborough, New York in 2016.

Kippenberger, Oehlen, and Büttner met in Berlin around 1979, not long after Büttner had dropped out of law school because he “couldn’t stand the crowd.” First, Kippenberger invited Büttner to be in a group show at a space he was running that was inspired by Warhol’s Factory. In the case of Oehlen and Büttner, they met after the former law student ended up in Oehlen’s apartment for a one-night stand with his female roommate. Büttner tells me the two chose painting as the best way to roll up their sleeves and do some real work in the world. “We talked for years about what has to done be done in art, looking at things and seeing what was missing, and then we started,” Büttner says. Their careers progressed in fits and starts. “We never thought that we would have international success, because our practice was based in the German language.”

They were determined to impress each other, at least, in what Büttner says was a “fruitful competition.” They also had a good time. Oehlen and Büttner founded imagined associations (like a sperm bank for refugees from the GDR, or the Church of Non-Differentiation) and engaged in reckless fun. Perhaps partying was part of the process. Büttner, Kippenberger, and Oehlen imbibed, and then imbibed each other’s ideas. They produced several exhibitions and artists catalogs in different constellations throughout the years, like Mahlen ist Wahlen (Painting is Voting) and Wahrheit ist Arbeit (Truth is work). In Germany, the rhyming titles bring a smile, yet something serious is being said. In Oehlen’s words, he called his early days “the most beautiful thing in my artistic life,” adding that a smile from either Büttner and Kippenberger was enough to know he had done some good work.

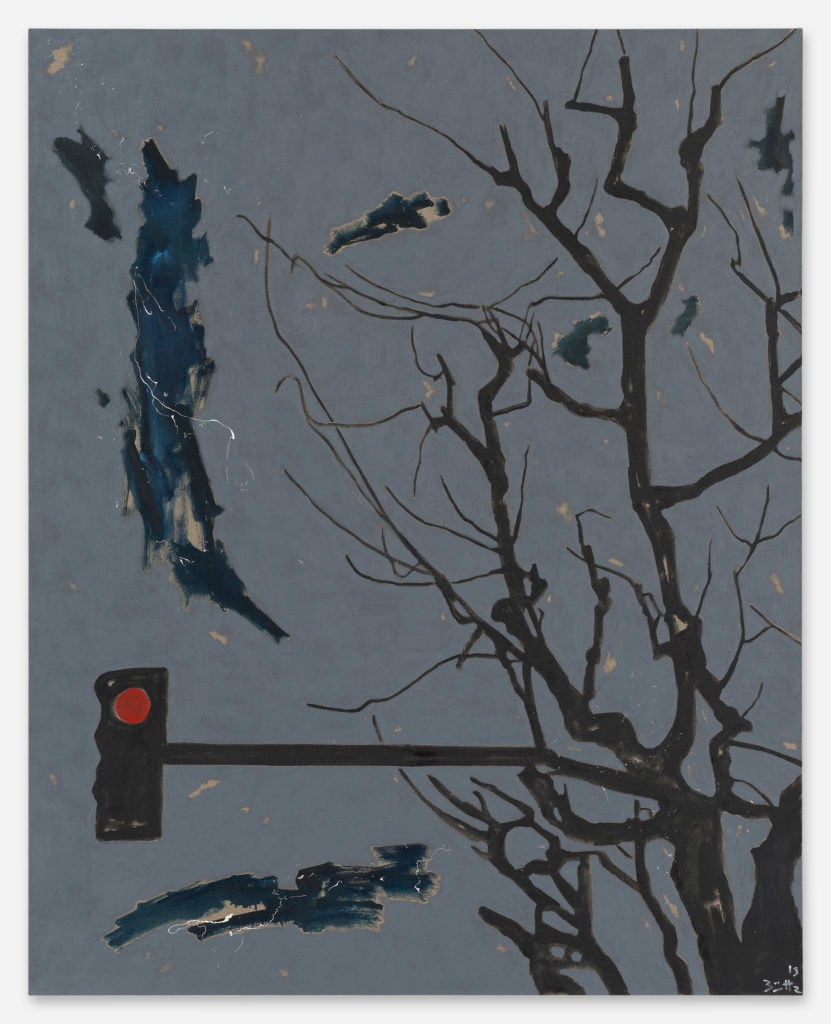

Werner Büttner, “Eines der unzähligen Neins meiner Tage” (One of the Countless Nos of My Day) (2019). Courtesy Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin.

In 2020, though, Büttner undeniably lags behind the profile of his rabble-rousing peers, at least in terms of market recognition. Heads turned in 2014 when Kippenberger’s 1988 untitled self-portrait sold at Christie’s New York for over $22 million to dealer Larry Gagosian, crashing past the artist’s previous records. That same year, Oehlen cracked the $1 million mark at auction. Though slower off the starting line, Oehlen’s market more officially lifted off when 1998’s Selbstportrait mit Leeren Handen went for nearly $8 million at Sotheby’s London last June.

Büttner admits he has been surprised by it all, but shrugs off any comparisons. “I recently asked Albert what it feels like to have reached this level in his career, and he said that the only thing that gets on his nerves is people talking about it,” the artist says. “He tries not to see it, and go on working.”

And so does Büttner. His new paintings are decidedly brighter, and still feel compellingly current. Questions about evil, faithlessness, hedonism, and political correctness abound. A red stop light forms the focal point of one work called One of the Countless Nos of My Day. “Art is over if we get new taboos,” Büttner tells me “You can’t talk about this world in a correct vocabulary.”

On that note, he is currently busy in the middle of setting up his foundation; it’s called Stiftung Störer des Stumpfsinns ins Leben (Foundation for Disturbers of the Whole Shit). Büttner’s always stood by disruptive causes. He’s also planning a mausoleum, though he expresses regret that the laws have changed in Hamburg; one can no longer leave dead bodies above ground, he laments. I can’t tell if he’s joking, but I decide it doesn’t really matter. As with everything he does, the meaning is as much in the gesture and attitude as the outcome.