In the 1980s, the German artist Albert Oehlen made work that was not exactly commercially viable. The first problem was what he called them: “Bad Paintings.” True to their label, they were intended to offend, or at least to polarize.

Unsurprisingly, then, people hated them. His comrade Martin Kippenberger—the bad-boy artist hero who worked alongside Oehlen, sometimes collaborating on joint works—saw his 1983 painting Portrait of the Artist as a Dutch Woman and exclaimed, “It is not possible to paint worse than that!” In 1984, perhaps testing Kippy’s theory, Oehlen made a straightforward, colorful, almost lovingly depicted rendering of Adolf Hilter, which he called, simply, Portrait A.H.

And so it is a bit of a surprise that, decades later, Oehlen is not just an artist who has captured the attention of institutions and more adventurous collectors, but of the most powerful players in the art market. His primary market prices have surpassed $1 million, and there is every indication that, in 2020, one of the paintings that simultaneously enthrall and revolt audiences could sell at auction for over $10 million.

Stoking interest is a sweeping career survey on view until February at the Serpentine Galleries in London, which spans the ’80s to the present (though it has received mixed reviews). In June, Oehlen’s market entered a new echelon when Selbstportrait Mit Leeren Händen (Self-Portrait With Empty Hands) (1998) sold for $7.9 million at Sotheby’s. (The auction house is also a sponsor of the Serpentine show, along with his three galleries.)

In the past year alone, Oehlen has had a solo show at Gagosian’s outpost in Hong Kong—which sold out before it even opened—and a special project at Gagosian Beverly Hills that coincided with the inaugural Frieze Los Angeles. In September, Per Skarstedt filled the tony Upper East Side gallery space with Oehlen’s late-’80s “Fn Paintings,” gloopy abstractions the artist once called “a step toward ugliness.” Nahmad Contemporary is currently presenting a show of Oehlen’s “Mirror Paintings,” canvases that depict different rooms—“museum, apartment, Hitler’s headquarters, things like that,” Oehlen has said. Another show of “Mirror Paintings” at Max Hetzler in London last fall included works sold for between $2 million and $4 million, sources say.

Demand for Oehlen paintings at auction—and not just for the “Bad Paintings,” but works from many stages of his risk-taking and varied career—has skyrocketed in the past few years. In 2016, 21 Oehlen works were sold, for a total of $5.2 million, according to the Artnet Price Database. Just a year later, that total had shot up to $21.2 million; and in 2019, a grand total of $31.5 million was made selling Oehlens at auction. In the span of a decade, Oehlen’s yearly haul increased by more than 4,000 percent.

There’s every indication that the prices could go even higher. Sources at Sotheby’s have said that, while the public auction records are splashy, works are selling for even more in private transactions.

‘No More Than Cleverly Made Abstractions’

Installation view, “Albert Oehlen: New Paintings” at Gagosian Hong Kong. Photo courtesy Gagosian.

Oehlen’s market has been a slow and steady build since he had his first solo show with Max Hetzler in 1981. Hetzler was then in Stuttgart, and in the years that followed, he moved the gallery to Cologne, where Oehlen, Kippenberger, and fellow rabble-rousing artist Werner Buttner had established a new scene—one where the artists not only worked together, but played together, carousing at local watering holes almost nightly. And the fierce competition drove them to new heights. As Oehlen recalled later, “This exciting relationship, in which each person in the circle would try to surprise the others, was the most beautiful thing in my artistic life. Just to get a smile from Martin and Werner was much more valuable than doing something with other people.”

By the 1990s, he had started to show in the States, first in a group show at Metro Pictures and then at Luhring Augustine Hetzler, the outpost that his Cologne dealer opened with Americans Lawrence Luhring and Roland Augustine steps from the beach in Santa Monica. Still, his work mystified some collectors. In an interview in 1994, the curator Diedrich Diederichsen kicked things off by telling Oehlen, “In the US, I’m often asked what Europeans like about your paintings, which Americans tend to see as no more than cleverly made abstractions.”

Installation view of the Albert Oehlen show at the Serpentine. Photo courtesy Serpentine Galleries.

The market seemed just as disinterested. Throughout the 1990s, even as a smattering of works came to auction, none sold for more than $30,000. The four lots offered in 1999 all sold, but brought in a paltry total of $52,382. Compare that to the attention lavished upon Kippenberger, Oehlen’s fellow Cologne buddy who died in 1997—a single painting of his sold at auction in 1999 for more than Oehlen’s total auction sales to date at the time.

But he was quickly establishing a cult of personality, and through regular shows in Berlin and New York, he began to build up a reputation as a dazzling shapeshifter, someone who could flit between abstraction and representation—and, in the early 1990s, the then-novel use of a Texas Instruments calculator to make the digitally-designed loops of his “Computer Paintings”—all while maintaining an affable, unpretentious presence.

“All the boxes were ticked with this one genius called Albert Oehlen,” said Martin Klosterfelde, a senior director at Sotheby’s who arranged for the consignment of the record-breaking Oehlen, which was previously owned by the German lawyer and art theorist Harald Falckenberg. “He’s never settled on an artistic style, he continues to be curious, he has a daring personality and he’s tried nuts things. And he doesn’t take himself too seriously—he’s obviously an academic painter, exploring what art does on a conceptual level, but he’s really playful about the whole thing.”

Influential early collectors include Eli and Edythe Broad, who snapped up the abstract paintings FN 26 (1990) and FN 23 (1990) in December 1993, as well as two more large works two years later. Other boosters included Rosa and Carlos de la Cruz, the Miami patrons who own the early painting Rotten Renaissance Rita (1984). Los Angeles collector Maurice Marciano bought early and often, as did Mexico City’s Eugenio López Alonso, heir to the Jumex fruit juice fortune.

Installation view, Albert Oehlen at Skarstedt, in New York.

By the 2000s, prices had inched up. A sold-out show of eight self-portraits at Skarstedt in 2001 were priced between $60,000 and $150,000. By the middle of the decade, Oehlen snagged his first solo show at a US institution, the Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami. (He was still polarizing; Walter Robinson wrote in these pages that Oehlen’s work is “an acquired taste—acquired by many important collectors, as it happens—not least because he never takes, as a painter, the ‘tasty’ way out.”)

In the lead up to the December museum show, two works came up for sale at Christie’s in London: one 1990 canvas sold for a respectable $159,235 over a high estimate of $106,157. But it was the second—also from 1990 and dominated by a large brown oval—that made a splash. Estimated to sell for between $44,232 and $61,924, it went for $430,290.

Over the next ten years, auction prices would stay mostly at that level, and finally cracking the $1 million mark in 2014. He had some extra muscle at that point, having left New York’s Luhring Augustine and London’s Thomas Dane for the global Gagosian empire in 2011.

Before joining Gagosian, primary market prices were in the $100,000 range. By the end of the decade, they had reached $1.3 million. Buyers included luxury-goods titan and Christie’s owner François Pinault, who snapped up the entire show the gallery’s Chelsea space in 2017 before staging his own solo show of the artist at Palazzo Grassi in Venice the following year. Pinault is one of Gagosian’s stable of collectors with seemingly unlimited access to art-buying resources, and a good number of them used such resources to start buying new Albert Oehlens.

“All of a sudden you do have Larry who came in, and he did give people a lot of confidence—and you had a lot of people join the team,” Klosterfelde said.

A Bold Online Sale

Albert Oehlen, Untitled, 1988, oil on canvas. © Albert Oehlen. Photo by Rob McKeever, courtesy Gagosian.

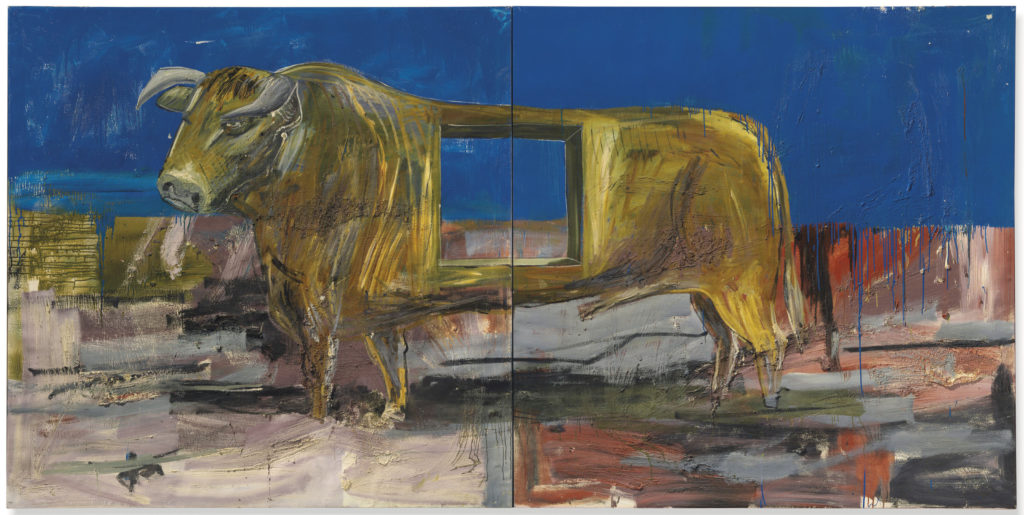

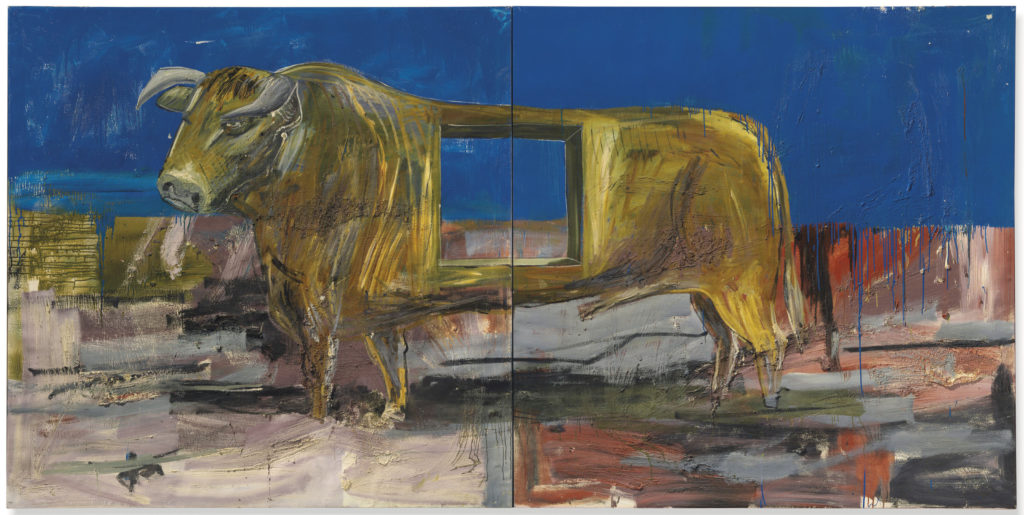

By the start of 2019, there was every indication that Oehlen could become one of the few dozen living artists with work that sells for more than $5 million. During a Frieze Week auction in October 2018, his dealers sat in the Christie’s salesroom and carefully arranged for works to blast over their estimates. First, the 1986 painting Stier mit loch (Bull with hole), a painting of a bull with a big square hole in its torso, sold to Max Hetzler, who was bidding against a representative from Gagosian, for a record price of $4.7 million. Then an abstract painting (washed unapologetically with magenta) sold for $4 million. It was underbid by Gagosian’s Andrew Fabricant.

Things got even more interesting in 2019, when Gagosian decided to devote a new sales model entirely to Oehlen. It was an online salesroom with just one painting, an abstract from 1988—one of the first he ever made. Timed to the opening of Art Basel Hong Kong, the viewing room came complete with a high-budget video of Gagosian directors discussing the painting’s brilliance and reams of data about the white-hot state of the Oehlen market. He was compared to other figures with hotter markets, like Christopher Wool (whose auction record is just south of $30 million) and Gerhard Richter (whose record is $46.3 million).

Albert Oehlen, Stier mit loch (Bull with hole) (1986). Photo courtesy Christie’s.

Why, then, shouldn’t Oehlen sell for those levels? And this one was only priced in the range of $6 million—more than the artist’s auction record at the time, but perhaps still good price for such a huge work, especially one that had been locked away for decades. The viewing room launched, and a timer started counting down from one week, at which point the room would shut down, deal or no deal, and the great Oehlen experiment would be over.

It didn’t need the full week. It sold in under two hours, to a collector who had never expressed much interest in Oehlen before. They bought it sight unseen.

From there, the artist went on to have pretty much a dream year. Different works topped $2 million at auction and, in June, Per Skarstedt sold a work out of his booth at Art Basel in Basel, Switzerland, for $2.5 million. Later that month, Skarstedt beat out David Zwirner to snag Oehlen’s Selbstportrait mit Leeren Handen (1998) at Sotheby’s London. That was the record-breaker, going for nearly $8 million.

Installation view of the Albert Oehlen show at the Serpentine. Photo courtesy Serpentine Galleries.

Which begs the question: Could 2020 be the year when Oehlen becomes one of the few painters alive who can sell work in the eight figures? There are hundreds of canvases floating around in storage and collectors’ homes. Have no doubt that some heavy-duty ones are getting consigned to the auction houses ahead of the contemporary sales at the start of March.

“Will we see a 10 or 20 million price in 2020? I don’t know, but if the right painting comes up…” Klosterfelde said. “There will be works coming to the market in 2020, definitely, and once the right painting comes to the market, then this story will continue.”