Art History

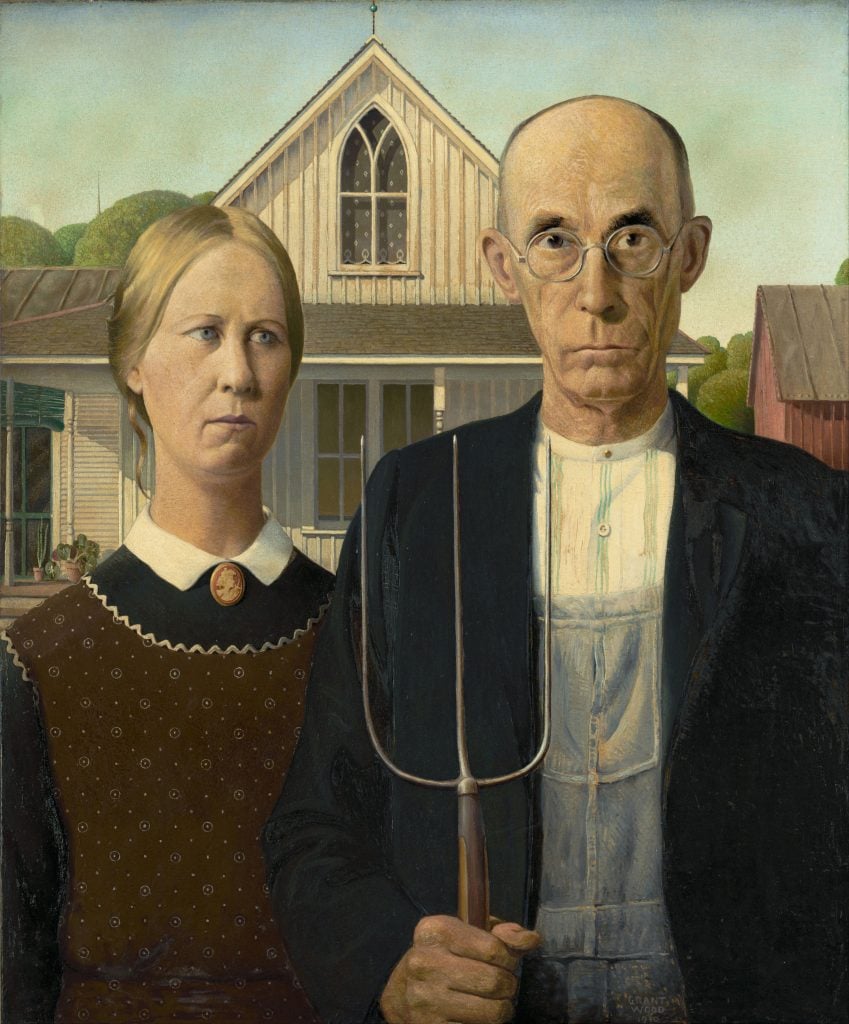

What Makes ‘American Gothic’ So Enduringly Famous?

There's much more to Grant Wood's iconic painting than meets the eye.

What gives some works of art incredible staying power while others fade into obscurity?

Consider the winners’ circle at the Forty-Third Annual Exhibition of American Paintings and Sculpture sponsored by the Art Institute of Chicago in 1930. First place went to Heinz Warneke’s carved marble figure The Water-Carrier. That work has been entered into the Smithsonian’s Index of American Sculpture, but no image or description is available, and it is listed as “unlocated.” It is instead the exhibition’s fifth-place entry, American Gothic by Grant Wood (1891–1942) that has entered into our nation’s collective cultural memory.

The painting’s essential elements—man, woman, pitchfork—have been referenced, reimagined, and parodied in everything from a 1942 photograph by Gordon Parks to a 2012 episode of My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic. In a New Yorker cartoon, the man, the Mona Lisa, and the Girl with a Pearl Earring walk into a bar. The next U.S. president and his or her spouse will inevitably appear somewhere in this iconic pose.

But as nearly a million annual visitors to the Art Institute of Chicago will tell you, the original image is worth a closer look. Here, we share three things that might help you see this timeless work in a new light.

The painting depicts a real house and real people

Wood’s inspiration for American Gothic was sparked by a leisurely drive around Eldon, Iowa, one spring afternoon in the company of a young art student, John Sharp. Just outside town, they happened on a little white cottage with simple board-and-batten siding and distinctive Gothic windows on the upper floor.

Wood, who had grown up amid Iowa’s no-nonsense farmhouses and had recently spent three months ambling through Munich’s soaring Gothic archways, was struck by this architectural curiosity. As legend has it, he told his friend to pull over, made a quick sketch on the back of an envelope, and fixed on the setting and title for what would become his—and perhaps America’s—most famous painting.

The house featured in the famous painting “American Gothic” by Grant Wood in Eldon, Iowa. Photo by David Howells/Corbis via Getty Images.

Of course, the artist wasn’t finished. Recalling, without a doubt, the sharply characterized Northern Renaissance portraiture he had admired in Munich and other points abroad, Wood had an idea: “To find two people who, by their severely strait-laced characters, would fit into such a home…I finally induced my own… sister to pose… The next job was to find a man…My quest finally narrowed down to the local dentist, who reluctantly consented to pose.” The dentist, Dr. Byron Henry McKeeby (1867–1950), had mixed feelings about his newfound fame: “I let him paint me on one condition” McKeeby wrote, “that nobody would recognize me… As soon as the people saw the painting,” he worried, that they would immediately single him out with alarm: “Why, that’s Doc McKeeby, the dentist, holding a pitchfork! Wonder if he’s going to use it on his patients!”

Wood’s sister, Nan Wood Graham (1899–1990), an artist and teacher in her own right, led a grassroots movement to preserve the American Gothic House, aka the Dibble House, soon after the artist’s death. The house now belongs to the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the exterior is open for photo ops daily from dawn to dusk. If you forget your hayfork, the nearby visitor center will lend you one.

Some of Grant’s fellow Iowans were furious

On November 6, 1930, the Des Moines Sunday Register published a reproduction of American Gothic with the misleading caption An Iowa Farmer and His Wife. The artist would later identify the two figures as father and daughter, not husband and wife; small-town types, not farmers, and Americans, not necessarily Iowans.

But the caption was the least of Wood’s troubles as letters to the editor started pouring in. One reader wrote: “On gazing at Grant Wood’s creation… I thought I might have discovered the ‘missing link.’ If this is a typical Iowa farmer and his wife, then heaven help me, for I, too, am an Iowa farmer’s wife.”

Another angrily added, “If this is all our work and progress has brought us… we might as well quit the job and take up bootlegging or some other up-to-date job! We at least have progressed beyond the three-tined pitchfork stage!”

Grant Wood, artist from Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Photo: Bettman/Getty Images.

Meanwhile, the Chicago Institute of Art, which had been persuaded by a patron to acquire American Gothic for its permanent collection, was receiving so much hate mail that it had to reply with form letters.

Born on a farm near Anamosa and lately employed as a public school art teacher in Cedar Rapids, Wood’s Hawkeye credentials were sterling. True, he spent his summers studying in Europe, and as a closeted queer man whose artistic inclinations had displeased his strictly religious father, he had reason to resent the heartland’s normative values. Yet Grant insisted that American Gothic was a tribute, not a sendup. In a 1941 letter to a fan, he explained as much, writing:

I did not intend this painting as a satire. I endeavored to paint these people as they existed for me in the life I knew. It seems to me that they are basically solid and good people…This Midwestern farm country is in my blood. By build and by disposition, I am a prairie schooner.

Soon enough, the artist would be embraced as one of Iowa’s favorite sons. He spent the remainder of his life mentoring local artists and championing the American Regionalist movement that immortalized the Midwestern sense of place and way of life. Wood was posthumously awarded the Iowa Award, the state’s highest civilian honor.

Interpretations range from the moral to the mythological

We know who posed for the painting, how viewers first reacted, and what the artist had to say about it all. But part of the staying power of great art like American Gothic is that it never stops giving rise to evocative meaning—the insights that arise when intention and perception collide.

Unveiled just one year after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, American Gothic can be seen as having captured the enduring spirit of the heartland. As the Great Depression ground on, it must have been reassuring to view the figures as personifications of the Protestant work ethic that built the nation and would get it rebuilt. This reading is bolstered by the fact that the figures’ starchy clothing and daguerreotype-like pose are decidedly old-school, even by 1930s standards.

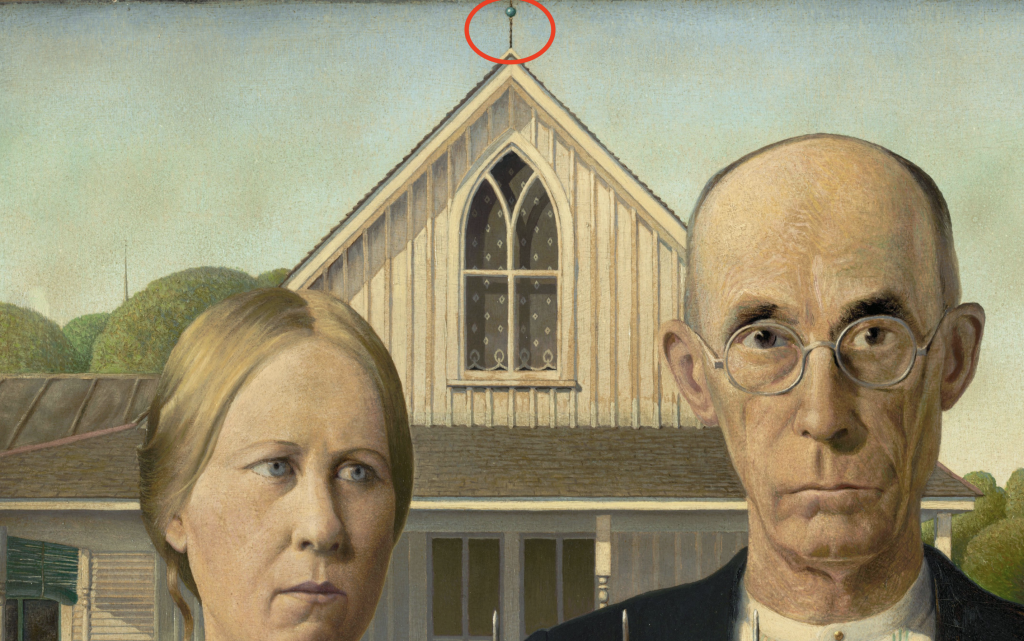

Detail of Grant Wood, American Gothic (1930). Found in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. Photo: Getty Images.

But some readings go darker and weirder. Writing for the New York Times, critic Deborah Solomon suggests that Wood “longed for the company of the dead” and that American Gothic is a mourning portrait, noting the drawn curtains in the daytime, the woman’s black dress, and the man’s expression of “somberness that is vaguely accusing.” Take a glimpse into the Victorian tradition of postmortem portraiture and you might agree that Solomon has a point.

Explained in his 2020 paper “Spinster Tales,” Bradford R. Collins’s interpretation is more ominous still: “Wood narrates the story of a relatively young, unmarried woman unhappily facing a bleak future of sexual repression…the [man’s] fist is best understood as…a demonstration of the grip he has on her libido as well as his own.”

But perhaps the most imaginative analysis of American Gothic so far was offered up by critic Kelly Grovier in A New Way of Seeing. He nimbly links a tiny, overlooked detail at the painting’s upper edge to a major astronomical discovery and a foreboding Greek myth:

Spinning against the weathervane… is a small gleaming blue sphere… News of [Pluto’s discovery] was rapidly orbiting the world…Suddenly, we are trapped in the gloom of a modern reimagining of the classical underworld, summoned before its irascible ruler, Pluto…And who is this standing beside him[?]…Proserpina, the goddess of grain and agriculture whom Pluto has abducted.

Ready to do your own close reading of Grant Wood’s American Gothic? You can view the painting in the Art Institute of Chicago’s Arts of the Americas wing, Gallery 263. In that room, you will also find Diego Rivera’s Weaving (1936) and Jacob Lawrence’s The Wedding (1948). The Institute holds two dozen other works by Grant Wood, including an early portrait of an Army buddy, but most or all are off view.