Art World

What Was the Most Influential Work of the Decade? We Surveyed Dozens of Art-World Experts to Find Out

What individual artworks from this era will stand the test of time?

What individual artworks from this era will stand the test of time?

Artnet News

As the turbulent and event-filled 2010s come to an end, we asked more than 100 artists, curators, gallerists, and other art-world figures to tell us their picks of the most influential art and art-makers of the decade. Here is a selection of their responses.

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirror Room (Phalli’s Field), 1965. Photo courtesy of Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc.

Without a doubt, Yayoi Kusama’s infinity rooms were inescapable in this decade. While she started making them in the 1960s—The Aldrich showed her in 1968—they have emerged to become the work for our selfie-obsessed moment.

—Cybele Maylone, executive director at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum

Laura Kimpton and Jeff Schomberg, #. Photo: Bill Hornstein.

# The hashtag is the most influential mark of the decade. Digital culture and the # have fundamentally changed the reception of #art, conversations around art, and who has access to #culture. #Instagram, introduced in 2010 and now the preferred social media platform of the #artworld, has altered how people experience art, from #selfies in #YayoiKusama #infinityrooms to memes of #MaurizioCatalan’s #banana. The hashtag has also mobilized conversations around #activism in art—#metoo #blacklivesmatter #decolonize #timesup—and has amplified the debates around #art #representation and #culturalappropriation.

—Eva Respini, chief curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston

Marina Abramović performs during the “Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present” exhibition at MoMA. Photo by Andrew H. Walker/Getty Images.

I chose Marina Abramović’s performance The Artist is Present at the MoMA in 2010, when Performance art entered the popular culture and Marina resurrected as a new icon. The event was a social and cultural moment involving an online sensation. It was the first artwork as a public spectacle, a life experience to be part of and to share with social media. Here was the beginning of a trend which became integral to the entire decade.

—Dr. Arturo Galansino, Director, Palazzo Strozzi in Florence

Hassan Hajjaj, Kesh Angels series (2014): The series confronted stereotypes, challenging Western perceptions of the hijab and female disempowerment. The series also played a role in bringing international attention to the exciting and experimental art scene of Marrakech.

—Touria El Glaoui, director 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair

Christian Marclay, The Clock (2011). Still courtesy of wikimedia.

For me this is a toss-up between three paradigm shifting projects, which each speak to the idea of the artwork as event across media: Christian Marclay’s The Clock (2010); Marina Abromivic’s The Artist is Present (2010); and Kara Walker’s A Subtlety (2014).

—Alexis Lowry, curator, Dia Art Foundation

Installation view, Carol Bove, The Foamy Saliva of a Horse (2011). Courtesy of the artist and Kayne Griffin Corcoran.

First presented at the 54th Venice Biennial, this was an artwork that literally and metaphorically stopped visitors in their tracks, refusing to be ignored. An eye-level plinth collected a free-association assemblage of found and exquisitely crafted objects. Comprising materials as varied as an oil can found on the Hudson River shore near the artist’s New York studio, an exquisite arrangement of shells, a silver woven curtain, driftwood, display structures, peacock feathers, and the blissful spaces between these and other objects, this was sculpture in action. The Foamy Saliva of a Horse pressed its way through the decade, forming a new lexicon that felt as if it had always been there.

—Lisa Le Feuvre, executive director of the Holt/Smithson Foundation

Random International’s “Rain Room” was displayed at the Yuz Museum in 2018. Photo courtesy of the Yuz Museum.

Christian Marclay’s The Clock. Random International’s Rain Room. Andrea Bower’s Open Secrets. Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian.

—Lisa Schiff, art adviser

Pierre Huyghe’s, Untilled (Liegender Frauenakt) (2015). Courtesy of MoMA.

Huyghe’s de-centered composition of “live and inanimate objects made and not made” on the grounds of a city compost facility—including two greyhound dogs, a live bee colony, and a groundskeeper—offered an unforgettable and strikingly disorienting reimagination of art in public space. It stands as a prescient harbinger of the societal decay and fragmentation that closes the decade.

—Olga Viso, fellow at the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and senior advisor at Arizona State University’s Herberger Institute

Installation view of Andrea Fraser, documenting the political contributions of board members of US museums.

The artwork that knocked around in my head the most was Andrea Fraser’s essay for the 2012 Whitney Biennial, ‘There’s no place like home’ in which she discusses the connections between Art, the patrons who finance it, and her culpability within that system. To look at recent protests and actions around the question of who funds our institutions, her investigations have had a big impact on more than just me.

I also have to mention the image of the decade for me is Judith Bernstein’s Union Jack-Off from 1967 that she showed in her show “Dicks of Death” in 2016 at Mary Boone. It was made in the ’60s, in the face of the Vietnam war, but I saw it the day after a Republican debate. That year brought Trump, and later Weinstein revelations, and stories of abuse from every industry… so yeah… Dicks of Death sadly relevant to this and many other decades.

—Gina Beavers, artist

Arthur Jafa, APEX (2013). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Arthur Jafa’s Apex is a cinematic sequence of direct, confrontational imagery that map the notion of “blackness,” both culturally as well as politically, through stark but intuitive edit, which bombard you against an apocalyptic soundscape.

—Krist Gruijthuijsen, Director, KW Institute for Contemporary Art

Dayanita Singh, Museum Bhavan (2013-). Courtesy of the artist.

Singh has a unique approach to photography, which reflects upon and expands the way we relate to photographic images. Most recently, Singh has developed a new format, a mobile museum, entitled Museum Bhavan. It contains a collection of museums, including the Museum of Chance, Museum of Little Ladies, or Museum of Furniture. The Museum Bhavan entails a dis-play system that allows her images from 1981 to the present to be sequenced, archived and viewed. Based on Singh’s interest in the archive, she presents her photographs here as interconnected groups of works allowing both poetic and narrative layers to emerge.

—Stephanie Rosenthal, director of Gropius Bau, Berlin

Atelier Issa Samb, Photo: Binna Choi. Courtesy of Studio International.

Issa Samb’s permanent and ever evolving installation of a courtyard-home-studio.

—Koyo Kouoh, executive director and chief curator of the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa

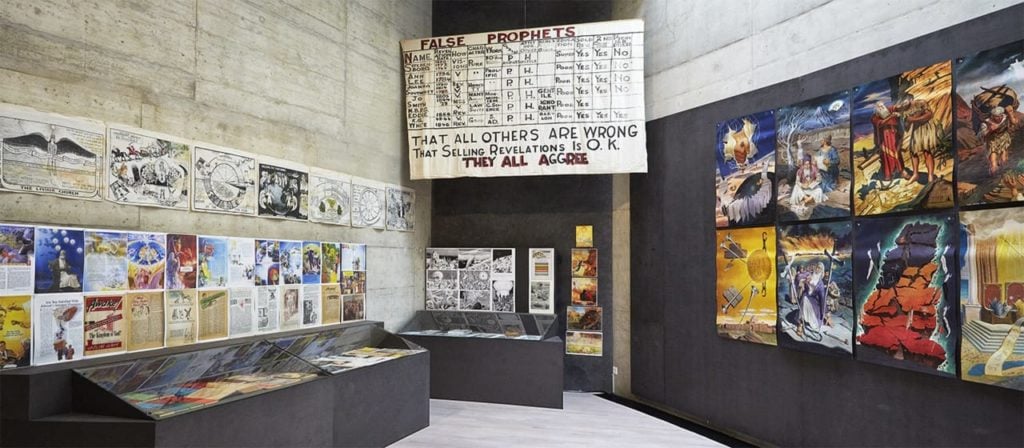

Jim Shaw, The Hidden World (2013). Courtesy of the artist and Simon Lee Gallery.

The Hidden World by Jim Shaw. Jim Shaw’s didactic art collection, collected over more than three decades, comprises thousands of objects—books, posters, magazines, T-shirts, record sleeves, and other illustrations—as commissioned by various sects, secret societies and spiritual movements of all kinds. The didactic purpose of this collection makes it impossible to classify as an artwork. And being created by amazing talents, it is also impossible to consider these items as regular objects. It embodies this floating state Marcel Duchamp was pursuing when he asked “Can one make works that are not ‘of art‘?”

—Marc-Olivier Wahler, director of the Geneva Museum of Art and History

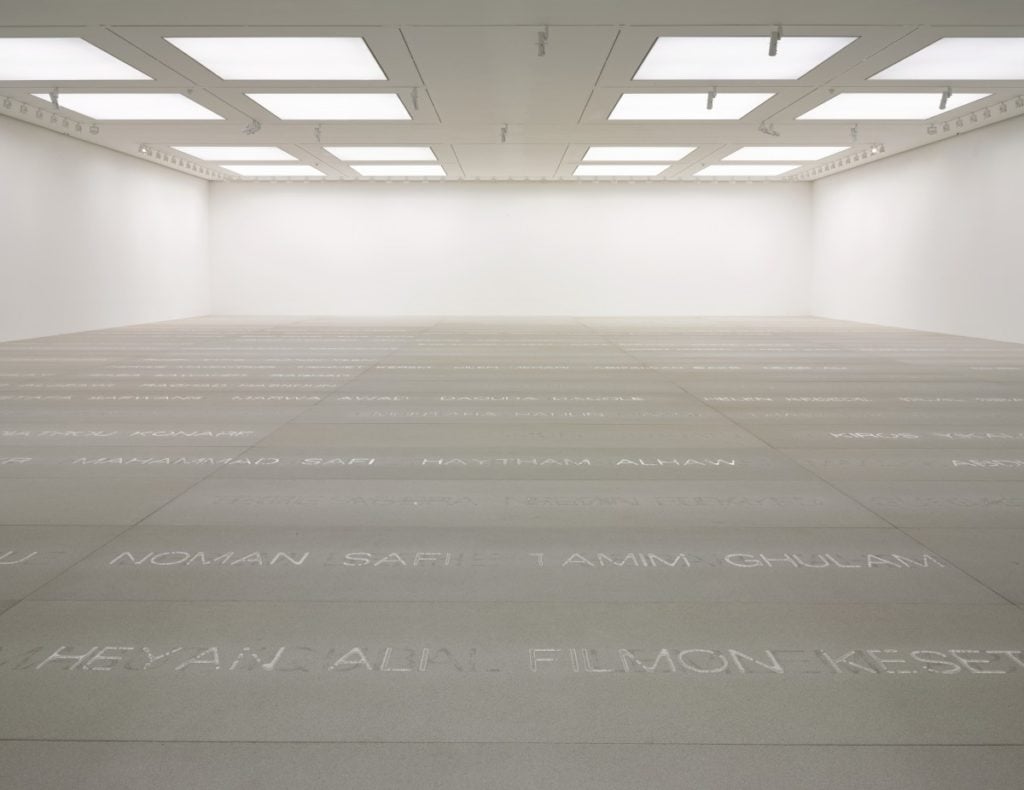

Doris Salcedo, Palimpsest (2013–2017). Courtesy of White Cube Gallery.

Doris Salcedo’s Palimpsest, first presented at the Palacio de Cristal, Reina Sofia in Madrid, is the most emblematic artwork of the last decade in the way it addresses the scale and cyclical nature of violence, outrage, and forgetting in various contexts around the world from mass shootings to refugee crises. Using nanotechnology and water, she and her studio collaborators invented a way for victims’ names (those who died crossing the Mediterranean to find refuge in Europe) to emerge from and dissolve into stone slabs. The work creates a space for public mourning where the shedding of tears meets systemic actions, and inactions, that cause these tragedies again and again.

—Julie Rodrigues Widholm, director and chief curator, DePaul Art Museum

Kara Walker’s A Subtlety…or the Marvelous Sugar Baby (2014). Image courtesy of gigi via flickr.

Kara Walker, A Subtlety. A Subtlety was an immersive arts exhibition on a dream scale. It took on challenging subject matter in a direct and demanding manner that pulled you in and did not let go. It is one of those works of art where an instant sense of community and kinship was established by those who experience it. A Subtlety presented a seamless dialogue between work and site. I hear of it time and time again as the inspiration for artists and institutions to think on a whole new scale.

—Justine Ludwig, executive director at Creative Time

Kara Walker, A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby (2014)

—Salvador Salort-Pons, director, Detroit Institute of Arts

Laurie Anderson, Habeas Corpus (2015). Courtesy of the artist.

Laurie Anderson’s work featuring former Guantanamo Bay-detainee Mohammed el Gharani addresses the personal costs of detention brought about by the war in Afghanistan, the longest war in America’s history.

—Melissa Chiu, director of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Maurizio Cattelan, America toilet in the Guggenheim Museum, New York 2016. Photo by Christina Horsten/picture alliance via Getty Images.

Maurizio Cattelan’s America, 2016 (a.k.a. the golden toilet). I believe that Nancy Spector should be considered a co-creator for her proposal to lend the work to Trump’s White House in lieu of the Van Gogh they requested, and that perhaps even the thieves who later stole the work from Blenheim Palace should be credited for contributing to the work’s storied life and influence thus far.

—Alexander S. C. Rower, president of the Calder Foundation

Arthur Jafa’s Love is the Message, The Message is Death (2016). Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York City, Rome.

Arthur Jafa, Love is the Message, 2016 and Kara Walker, A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, 2014. As Jafa has said, our time doesn’t need masterpieces, it needs conversations: these two works actually qualify on both counts.

—Catherine Morris, curator of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum

Arthur Jafa’s Love is the Message the Message is Death is just incredible and it is a continued point of reference for so many artists.

—Javier Peres, gallerist

This video essay is a masterful convergence of found footage that traces African-American identity through a vast spectrum of contemporary imagery. From photographs of civil rights leaders to helicopter views of the LA Riots to a wave of bodies dancing to “The Dougie,” the meticulously edited seven-minute video suspends viewers in a swelling, emotional montage that challenges what it means to contribute to the vast and complex terrain of Black representation.

—Arnold Kemp, Dean of Graduate Studies, School of the Art Institute of Chicago

The large-scale public art installation titled Seven Magic Mountains by Swiss artist Ugo Rondinone near Jean, Nevada. Photo: David Becker/AFP/Getty Images.

Ugo Rondinone’s Seven Magic Mountains in the Las Vegas desert. A major work by one of the art world’s favorite artists.

Additionally… Ugo Rondinone created (as opposed to “curated”) a living work of art in the form of the museum retrospective “I Love John Giorno” at the Palais de Tokyo, which went on to tour 13 nonprofit institutions in New York. Not only did it influence so many generations, but it was one of the most memorable and poignant museum shows for me and many friends in the past decade. Given John’s recent passing, that experience is even more meaningful now as we look back.

—Elizabeth Dee, cofounder and CEO, Independent Art Fair

Pierre Huyghe, After ALife Ahead (2017). Courtesy of the artist, Marian Goodman Gallery.

I hope it’s Pierre Huyghe’s large installations at the Skulptur Projekte in Kassel in 2017. It opened a door to the poetry of virtual worlds and also prophetically hinted at forms of biological computing that—I am hopeful again—will not suck so much energy that it makes our planet uninhabitable.

—Daniel Birnbaum, director, Acute Art, and former director of the Moderna Museet

Huma Bhabha, installation view of the Roof Garden Commission “Huma Bhabha: We Come in Peace,” We Come in Peace. ©Huma Bhabha, courtesy of the artist and Salon 94. Photo by Hyla Skopitz, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Huma Bhabha’s “We Come in Peace” on top of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Completed in 2018, that sculpture captured fraught power dynamics. It is grotesque, melancholic. It is a commentary on otherness; and relevant to the plight of refugees and the crisis of globalization felt around the world.

—Jason Stopa, artist

Carrie Mae Weems, “With Democracy In The Balance There Is Only One Choice” (2018). Courtesy of For Freedoms.

Launched in June 2018, during the midterm elections, it is the largest creative collaboration in American history and offers a new and compelling model for both art-making and political engagement. 52 artist billboards (1 per state, plus Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C.) were commissioned, and over 600 events were held nationwide with over 250 partners ranging from museums to university art galleries to public libraries to churches to individual artists. For Freedoms tapped into an under-appreciated national resource, namely our extensive civic infrastructure, to create diverse and decentralized platforms—unique to and created by individual communities to address and give voice to their specific needs—for engagement, dialogue, and creative problem-solving. In a decade marked by political turmoil, deep polarization, generational division, and rising inequality, the 50 State Initiative shows us how expansive an artwork can be, and highlights the important and unique role that artists can and do play in society.

—Rujeko Hockley, assistant curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art

Former U.S. President Barack Obama and former first lady Michelle Obama stand next to their unveiled portraits at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty Images.

An almost impossible question to answer! I’ll go for Amy Sherald’s Michelle Obama portrait which has captivated so many people.

—Manuela Wirth, president and co-founder of Hauser & Wirth

Portraits of former President Barack Obama and Mrs. Michelle Obama by artists Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald.

—Christopher Bedford, director of the Baltimore Museum of Art

I’d include the portraits of former President Barack Obama and Mrs. Michelle Obama by artists Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald, respectively. They were among the most influential and widely seen artworks of the decade, and forever changed depictions of presidential power in this country.

—Cara Starke, director of the Pulitzer Arts Foundation

The Obama portraits by Amy Sherald and Kehinde Wiley. They have set visitor records at the National Portrait Gallery, and created a new discourse around official presidential portraiture and Black artists. They have also inspired books (Parker Looks Up and a forthcoming volume with an essay by Richard J. Powell about the significance of the portraits).

—Bridget Cooks, professor of African American studies and art history, UC Irvine

Art from the Digital Art Museum: teamLab Borderless. Photo courtesy of teamLab.

Team Lab crew works at the intersections of art and technology. Their work, which we have seen all over the world (I saw their massive Tokyo installation in July) in the past year or two is pushing the limits of machine learning as in integral part of experiential work. They are bold, forward-thinking, and orienting us toward the future.

—Isolde Brielmaier, curator, International Center for Photography, and professor, Tisch’s Department of Photography, Imaging and Emerging Media at New York University

Thomas Hirschhorn, Robert Walser-Sculpture (2019). Courtesy of the aritst.

I opt for Thomas Hirschhorn’s Robert Walser-Sculpture, 2019, curated by Kathleen Buehler, because for a fraction of time during this summer in the small city of Biel in Switzerland it fulfilled the utopian dream of a social sculpture, brought together by lots of tape and love for Robert Walser: diverse scholars, psychopaths, artists, children, alcoholics, writers, esperanto-fans, Ethiopian cuisine, and local beer.

—Nina Zimmer, director, Kunstmuseum Bern and the Paul Klee Center

Kehinde Wiley, Rumors of War (2019). © 2019 Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Times Square Arts, and Sean Kelly. Photo: Ka-Man Tse for Times Square Arts.

Kehinde Wiley’s monumental bronze sculpture of a young African-American man wearing urban streetwear and sitting astride a massive horse was launched with pinpoint accuracy in New York City’s Times Square. When it finds its permanent home at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond it will stylishly lead the way in advancing a broad range of critical art issues, including the representation of previously neglected subjects and how best to respond to civic monuments glorifying discredited “heroes” of the past.

—Michael Brand, director, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Works by Richard Prince at Gagosian Gallery’s Frieze booth.

Artwork that explored social media as a medium in general. Social media was born before 2010, but in the last 10 years its influence has rocked our lives and completely reshaped how every person shares and consumes content, and interacts with each other. Richard Prince’s Instagram art was very inspiring, and he was in his 60s when he created them!

—Adrian Cheng, founder K11 Art Foundation and K11

Argentinian artist Marta Minujin poses inside the ‘Parthenon of Books’ at the Documenta 14 art exhibition in Kassel. Photo: Ronny Hartmann/AFP/Getty Images.

It’s hard to pinpoint a specific art work, but I would say social practice. Over the past decade we’ve seen artists work more and more outside institutions, collaborate and make work to benefit different communities. I see this movement rooted in the work many Latin American artists were doing in the 1960s, such as Julio Le Parc and the collaborative GRAV, Techo de de la Ballena, Marta Minujín, many of the artists in Radical Women, etc.

—Estrellita Brodsky, curator, collector, and philanthropist

Installation view of “One Basquiat” at the Brooklyn Museum. Image: Ben Davis.

That’s a really difficult one for me to answer. I can’t say there is only one. And sometimes artists are not as influential for their artworks as they are for other aspects of their endeavor. There have been several artists that have been influential for different reasons.

The fact that a Jean-Michel Basquiat painting became the most expensive artwork by an American artist will have enormous influence on the pricing of art by other African-American artists from now on.

The fact that artist Steve McQueen won an Oscar for Best Picture for an uncompromising film he made about slavery has been enormously influential in shifting Hollywood’s attitudes regarding black film production and subject matter.

Of course there are memorable artworks of the past decade by such artists as Hito Steyerl, John Akomfrah, Doris Salcedo, Cameron Rowland, Teresa Margolles, but I am also very interested in social and political gestures by groups such as GULF, Nan Goldin and PAIN, Kader Attia and his La Colonie Project in France, and the SIN 349 and San Isidro Movement in Cuba.

—Coco Fusco, artist, writer, and curator