Much has transpired since 2019 when Whitney curators David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards were announced as the next organizers of the institution’s flagship biennial: a pandemic, a presidential election, a wave of protests. Even the date of the always-anticipated exhibition changed, moving from 2021 to April of this year.

Tasked, as all Whitney Biennial curators are, with staging a show that reflects the times into which it’s born, Breslin and Edwards found themselves in a difficult position. They had to track down art that captured the spirit of those world-altering events without trivializing or exploiting them—and do a lot of that work over Zoom.

With that kind of brief, it’s unsurprising that the biennial almost always produces controversy.

For their turn in the hot seat, Breslin and Edwards took an open-ended approach that may successfully turn down the collective temperature. They opted to ask questions instead of offering declarations, to create a space for contemplation, and to look beyond the borders of America for a portrait of the country.

Ahead of the opening of the exhibition, “Quiet as It’s Kept,” Breslin and Edwards spoke to Artnet News about the curatorial experience and what viewers can expect.

Alfredo Jaar, still from 06.01.2020 18.39 (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Lelong & Co.

The idea of designing an exhibition to reflect the art of our times is daunting at the best of times, but the last three years have not been the best of times, and much has changed since 2019 when you two were announced as curators of the biennial. Does that distinguish this biennial from others in your mind?

David Breslin: Well one amazingly consistent thing was working together with Adrienne. Because I do think that in the best of times, these are hard shows to do and, as you say, these have not been the best of times. To have someone that you trust, respect, and admire, someone you have absolute faith in, is really important.

To the other point, I would say that, for every person who does a biennial, whether they’re at the Whitney or elsewhere, the sands are always shifting; the times and the ways in which artists are reacting to them are constantly changing. I think the degree of change in such a brief period of time is something that Adrienne and I had to reckon with in a way that felt really alive to the moment. But we also didn’t want to claim or sensationalize any particular part of it. We were thinking about how the exhibition can reflect the complicated layers of emotion that we’ve all felt.

Adrienne Edwards: One of the things that really rocked me was when we got on the museum floor before artwork started coming in. It was just this clearing; it was completely open and there was nothing there. In some ways it felt deeply metaphorical and emblematic of what we needed and had hoped for. David and I felt it was important to put together this show, wanted to contextualize artists in relationship—all the stuff you can read in the essay and the press release. But what was really moving was realizing what it meant to stand there and see all of these radical juxtapositions, all of these incredible things—and not just side to side, as we’re accustomed to seeing them, but how you could get a sidelong glance that takes you across 15,000 square feet and see a relationality there. That really opened things up in a way that reinforced that we were onto something when we set out to make a show that was about the conditions in which we were living.

Adam Pendleton, still from Ruby Nell Sales (2020–22). Courtesy of the artist.

How has your approach to the show evolved since 2019?

DB: From about November 2019 to mid-March, when we were told that the museum was shutting down for what was then thought to be a brief moment, we were on the road. It was a traveling moment. It was about going into studios, getting on planes, seeing people from afar, roaming around New York, seeing people that were closer by. But even before that, Adrienne and I had a lot of time to just sit together with artists names or images we wanted to share with each other or books or essays or articles that proved to be formative. Then, in mid-March, everything shifted and, like that, we were on Zoom.

Adrienne and I had to develop a different kind of relationship with each other too. When you’re in the same space, you take for granted that you can just meet up and have a chat. It suddenly had to be very deliberate. But I was surprised by how much more intimacy that allowed for. All the texts that we have, the photos that we’ve sent back and forth, even images of pages from books that we were reading—I still remember that as being a really grounding thing when we were pretty much by ourselves or with our families in that moment.

The phrase that forms the name of the show, “Quiet as It’s Kept,” opens Toni Morrison’s novel “The Bluest Eye.” It was also the name of an album by bebop drummer Max Roach and an exhibition curated by David Hammons. What does it mean to you?

AE: It’s a kind of vernacular that I would hear from my grandmother and women of her generation. It’s this very kind of tongue-in-cheek thing like, ‘I’m going to tell you something you already know, but you never talk about.’ [Laughs] It just worked for us. So did the fact that those sources are interdisciplinary references, because that’s such an important part of the show. Trying to speak to identity or a sense of belonging or history or social formation—those are all things that David and I were thinking about very deeply. So it just seemed to be the perfect title.

Coco Fusco, still from Your Eyes Will Be an Empty Word (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Alexander Gray Associates.

You’ve used somewhat soft language to describe the show—language that suggests rather than states. You’ve called the exhibition “speculative” and an “experiment,” described the subthemes as “hunches,” and the group of artists as an “ensemble.” Fair or not, we tend to associate the Whitney Biennial as a kind of declarative, flag-in-the-ground kind of exhibition—and because of that, it almost always proves to be alienating to some people. I wonder, with this new language, are you trying to get away from that understanding and move toward something more nuanced and contemplative?

AE: I would say it’s necessarily contemplative, given the times in which it’s been made. How can you have any sense of certainty about anything really? It would seem absurd.

That clearing on the fifth floor that I mentioned before, it’s really about leveling and holding space, it’s about the importance of everyone being able to ask questions, to show up with our own experiences and have those brought to the fore.

This whole idea that any singular exhibition could be declarative is already deeply problematic and, at the Whitney, there’s a kind of institutional openness and clarity about that impossibility. Because institutions are changing too. These institutions are comprised of people, so every time you have a different cast of characters here, you’re going to get a different kind of show. What the Whitney Biennial was 20 years ago, what it was 30 years ago—it’s really different from what the Whitney Biennial is now. And you know what? That feels really right and honest and generative.

DB: I think we find that there’s real strength in speculation. Instead of leading with our own kind of declarations of what it should be, we wanted to situate the show as an encounter with different ways of imagining a world. Some exhibitions revolve around this question of, “Well what power does art have to change the world?” They have these very grandiose ideas. In no way are we thinking that it can’t, but we believe art has a way of impacting and changing people, how people think and respond. And then people have a way of changing the world or reacting to it. There’s never going to be any singular story that a show like this can narrate. So it became a question of how we might be able to create an ensemble where there are multiple narratives that can bleed in and out of each other.

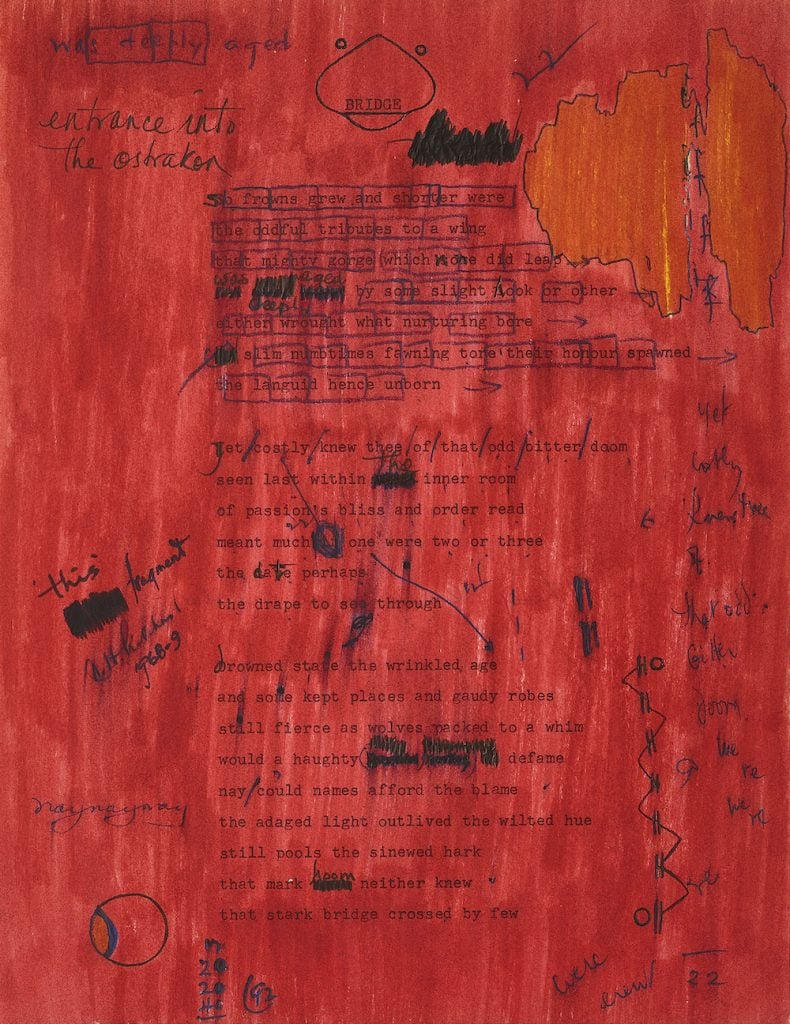

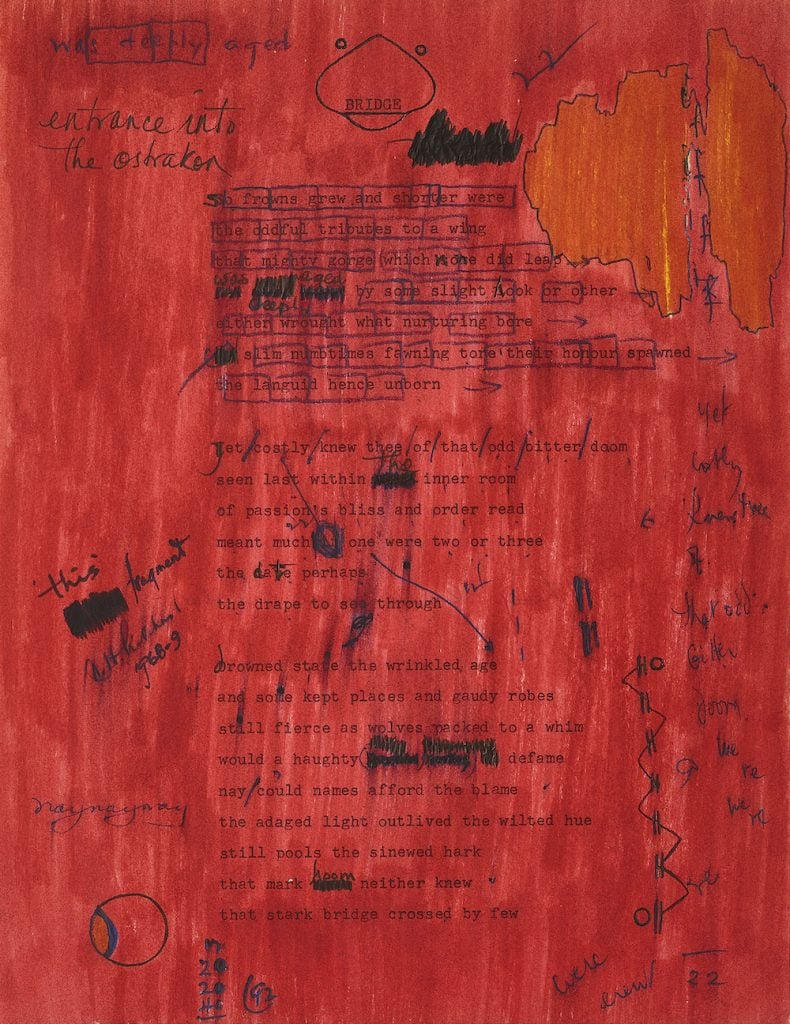

N. H. Pritchard, Red Abstract / fragment (1968–69).

Accompanying the exhibition’s wall texts and other materials is a symbol that comes from the avant-garde poet N. H. Pritchard. It’s a set of inverted parentheses: ) (. What does that motif mean to you?

AE: Pritchard is an artist that I’ve come to know in my relationship with [Whitney Biennial artist] Adam Pendleton, who also has reprinted some of his work. The symbol seemed so iconic to David and I, the profound openness it suggests. I think about it as an interval, a space between two marks. It’s so emblematic of where we are in this moment, this in-between space, ready to get on with it. Also, the fact that it was done in ’68, another troubling and complicated year, and still resonates across time is incredible.

Prichard as a figure was so interesting. He traversed these really different worlds and always seemed to be a little too eccentric for both of them in some ways. What we were able to see in the estate was his poetry, but with a visual lexicon added to it. There are these really dazzling, colorful drawings overlaying the language itself. Pritchard’s poetry is very compelling, but it’s not closed in terms of its symbolism or signification. It’s actually profoundly open. Those are all things that Dave and I had been saying we wanted to put into this exhibition.

DB: Adrienne, I still remember when you and I met with Ian Russell, Pritchard’s nephew. We were looking at some drawings and poems—I think it was in August of last year. There were so many times we just looked at each other and we didn’t have to say anything, we just kind of knew. It was one of those great moments that come with working with someone for a long time. When we saw that symbol, our eyes met and we thought, ‘All right, we’re going to do something with this one.’ [Laughs] You will see it on the side of the introductory texts. It’s incorporated there as a nod to this other way of looking and seeing.

Your biennial includes artists outside of the U.S.—specifically from Canada and Mexico—which is not new for the Whitney Biennial, but might nevertheless confuse some who are expecting a survey of American art.

DB: It was very important for us to think about “The Whitney Museum of American Art” and the fact that that can mean so much for so many different people. Obviously, people who visit aren’t just from the United States, and the work that people make within the United States has ramifications everywhere in the world. That’s something Adrienne and I took very seriously in putting on this exhibition, that there is a kind of push and pull relationship between the United States and the countries closest to us. The artists who are working on the border of Tijuana aren’t just being shown on their own. They’re incorporated within a flow of other artists and works that touch on similar themes about, say, how pop culture is defined or minimalism is thought about. We wanted to make an exhibition that looks like what America really looks like, which is a country of immigrants, a country of pressure along the border.

Denyse Thomasos, Displaced Burial / Burial at Gorée (1993). Courtesy of the Estate of Denyse Thomasos and Olga Korper Gallery.

There’s a tonal dichotomy between the show’s top floors—one light and open, the other dark and labyrinthine. What is the relationship between these two sections?

AE: The sixth floor is a labyrinth. There is, almost in a Borgesian kind of way, an unfolding of different kinds of spaces and rooms. Unlike the fifth floor, your experience is far more directed. You’re directed through this antechamber and then you can come out of that and you can go left or right, you can go forward. So there are these undulating, changing experiences there. That floor has a lot of moving image work, which is often presented out in the open because we have literally transformed the floor into a black box itself. It really feels like a void; it has a force to it. Then, on either end, there are these works that are deeply about light.

So as intense as I think it’s shaping up to be on the top floor, it’s actually optimistic. It tries to embody the possibility of something else. I think of that floor as characterizing both a sense of history and also this contemporary moment, the last two-plus years of life in the United States. Deeply encapsulated in that space are our issues, our hopes, our disappointments. But there’s a way out if we choose to take it.

“Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept” will be on view April 6 through September 5, 2022 at the Whitney Museum of American Art.