People

Art Collector William Arnett, Champion of Thornton Dial, the Gee’s Bend Quilters, and Other Outsider Artists, Has Died at 81

Arnett founded the Souls Grown Deep Foundation in 2010.

![William Arnett, right,] with his son, Matt Arnett. William Arnett, right,] with his son, Matt Arnett.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2020/08/052817_matt_arnett_ba44-mr-1024x576.jpg)

Arnett founded the Souls Grown Deep Foundation in 2010.

![William Arnett, right,] with his son, Matt Arnett. William Arnett, right,] with his son, Matt Arnett.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2020/08/052817_matt_arnett_ba44-mr-1024x576.jpg)

Taylor Dafoe

Art collector William Arnett, who helped bring the work of Black, self-taught Southern US artists to the mainstream art world, died last Wednesday, August 12, in Atlanta, Georgia. He was 81.

The news was shared by the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, the non-profit Arnett founded in 2010 with his extensive collection of works by vernacular artists, including Thornton Dial, Lonnie Holley, and the Gee’s Bend quilters.

Since its establishment, the foundation has placed over 400 pieces by 110 artists in numerous high-profile collections around the country, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

“He saw something where other people didn’t. I cried for several days after hearing of his passing because he had treated me like a brother,” Holley told Artnet News. “He elevated our art to a much greater level of appreciation. Even to us.”

“Without him, most of us would have been waiting and waiting for people and museums to digest and appreciate our art as arts of America,” Holley added. “It just wasn’t happening. He gave his life so that our art didn’t have to ride in the back of the bus.”

Lonnie Holley, Sandstone Sculpture (1985). Photo: Courtesy of the artist and James Fuentes, New York.

Arnett was born in Columbus, Georgia, in 1939. In college, he found a passion for ancient art history and spent several years after graduation traveling around Europe. In 1964, he joined the Air Force reserves and four years later was stationed outside Atlanta, where he settled.

After leaving the Air Force, Arnett made several trips to Europe and Asia and began his art-collecting career by purchasing Hittite pottery and Chinese porcelain. Later, he collected ancient Mediterranean and West and Central African art.

His father, who owned a dry goods company, supported Arnett’s early acquisitions and eventually left him with an inheritance that was put toward acquisitions.

In the early 1980s, Arnett discovered the work of Americans then known as outsider artists, and soon thereafter made a habit of cruising backroads in Alabama and Georgia, looking for new discoveries.

He would often pay these artists weekly stipends, encouraging them to focus exclusively on their creative pursuits and sell their work. Within a decade, his collection of several hundred artworks filled his house and, eventually, an entire warehouse.

![William Arnett [R] with Thornton Dial. Courtesy of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2020/08/TD_Portrait_w_Arnett_049.jpg)

William Arnett, right, with Thornton Dial. Courtesy of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation. Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio.

And some considered his relationship to Southern artists exploitative. In 1993, “60 Minutes” ran a segment on outsider art that depicted Arnett as a vampiric white collector profiting off the work of his artists. Following the show’s airing, exhibitions of these artists’ work were canceled, and collector interest abated.

“My concerns were how he functioned as a patron with artists who were, by and large, poor,” Susan Krane, the former director of the San Jose Museum of Art, said in a New Yorker profile of Arnett. “He was providing a stipend and materials, and owning or selling the art. Was there an aspect of colonialism that infiltrated his position as a patron?”

“There was also a question because Bill was creating art history around these artists while functioning as a dealer and promoting exhibitions,” she added. “If you’re a museum person, it raised every red flag you’re taught to pay attention to.”

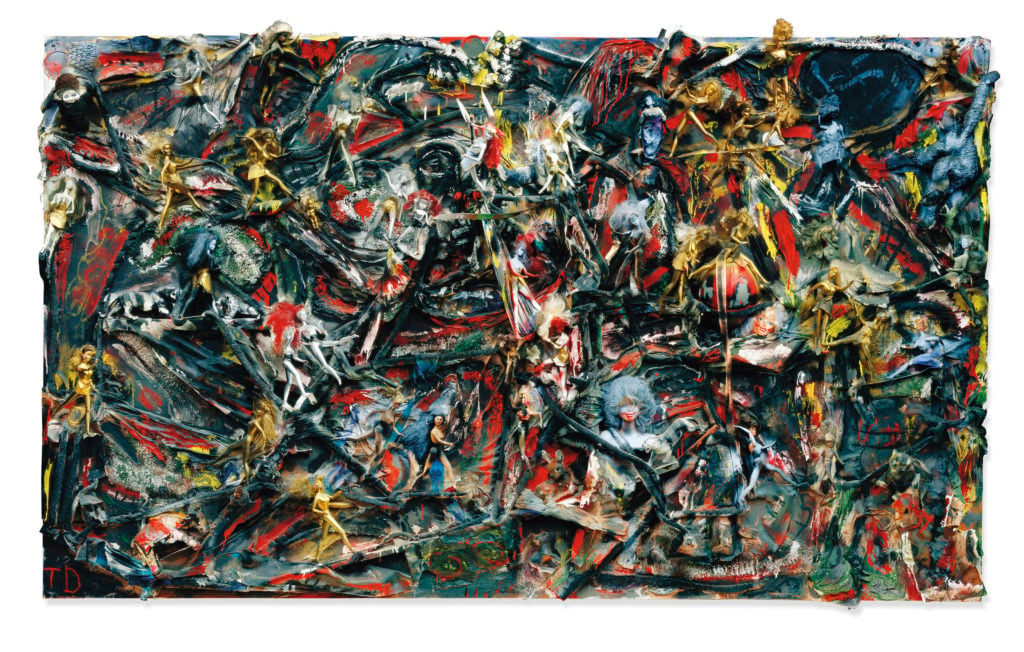

Thornton Dial, Trophies (Doll Factory) (1999). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

But others felt the criticism was unwarranted.

“Bill’s unflagging dedication to the Black Belt artists he championed sometimes put off the uninitiated,” said Maxwell Anderson, president of Souls Grown Deep.

When asked what he’ll remember most clearly about Arnett, Anderson recalled a story that encapsulated the collector’s complexities.

“His insistent advocacy was leavened by humor, once eliciting a deep-throated laugh from Mrs. Clinton at a White House reception in 1995,” Anderson said. “Accompanying Lonnie Holley to his installation in the First Lady’s sculpture garden, Bill was the consummate diplomat, yet equipped with wicked wit.”

“That combination of passion, impatience, and intelligence was unique to him.”

In 1996, Arnett lent 450 works from his collection to “Souls Grown Deep: African-American Vernacular Art of the South,” a critically acclaimed exhibition at the Carlos Museum at Emory University in Atlanta, which remains among the most comprehensive surveys of the self-taught southern artists ever mounted.