Archaeology & History

William Blake’s Earliest Etchings Uncovered in Stunning High-Tech Scans

Some of Blake's markings are too small to be seen with the naked eye.

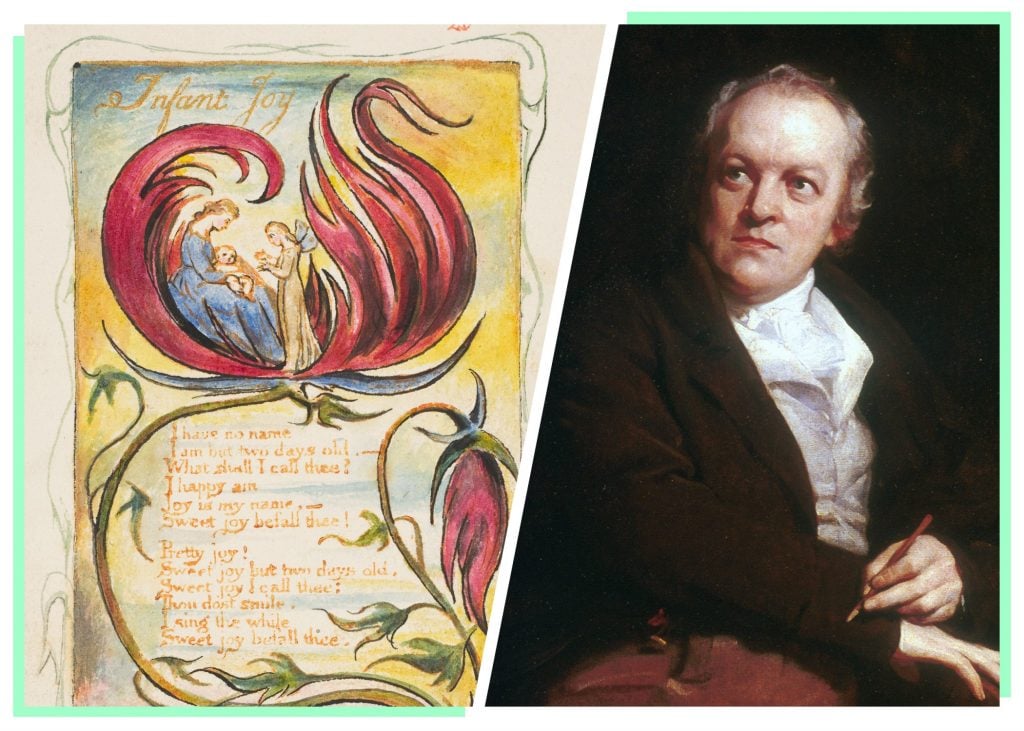

Oxford University’s Bodleian Libraries has announced the discovery of lines, swirls, squiggles, and doodles worth getting excited about. They belong to William Blake and are believed to be the earliest evidence of the 18th-century poet-artist’s engravings.

The markings, many of which are invisible to the naked eye, stem from Blake’s stint as an apprentice at the studio of master engraver James Basire in the 1770s. Spread across the reverse of a series of copper plates, they were discovered by Mark Crosby, a literature professor at Kansas State University, using the libraries’ ARCHiOx technology, which is able to scan the surface of objects at over one-million pixels per square inch.

Etching believed to be by William Blake showing a face. Photo: courtesy Bodleian Libraries.

They are the rough pads for the practicing artist, ones never intended to be seen. Some of the engravings show Blake methodically learning Basire’s house style with burin and dry point compass in hand. There are plates thick with hatching, cross hatching, semi-circles, and motifs—markings that were the essential basics for engraving illustrations.

An arrow etched by William Blake on the verso of a copper plate. Photo: courtesy Bodleian Libraries.

Other plates show the wandering mind (and hand) of a young Blake, who began working for Basire as a 15-year-old. It seems, at points, he grew distracted. One instance shows a miniature face, made up of eyes and their brows, a crossed-out nose, and a sliver of a mouth. In another, Blake hatches the “O” of “London,” as though idly coloring it in. In a third, he etched a short-shafted arrow, a motif he would later use in two of his watercolor paintings of Milton’s Paradise Lost.

Verso of a copper plate showing a plate maker’s mark by Blake. Photo: courtesy Bodleian Libraries.

“For the first time since they were made, we can now see the practice work and doodling of the young apprentice,” said Crosby who has been researching the history of the Bodleian plates and is fairly certain the markings belong to Blake. “The tiny visionary face that emerges from the copperplate to return our gaze across two and half centuries.”

Verso of a copper plate showing dots, hatch, and lines practiced by Blake. Photo: courtesy Bodleian Libraries.

The plates were created as accompanying illustrations to Sepulchral Monuments in Great Britain by Richard Gough, an antiquarian whose work focused on English tombs from Norman Conquest to the 17th-century. Gough commissioned Basire’s studio to create illustrated reproductions of medieval tombs including those in Westminster Abbey. Although Gough attended Cambridge University (he left without a degree in 1756), the plates were bequeathed to the Bodleian Libraries in 1809.

Crosby’s research is set to appear later this year in Print Quarterly and Blake Illustrated Quarterly.