Art & Exhibitions

The Woman Behind Iraq’s Pavilion in Venice Launches a New Initiative to Champion Artists From Conflict Zones

Tamara Chalabi is expanding the Ruya Foundation’s mission beyond Baghdad and Venice with the launch of Ruya Maps.

Tamara Chalabi is expanding the Ruya Foundation’s mission beyond Baghdad and Venice with the launch of Ruya Maps.

Javier Pes

The Baghdad-based Ruya Foundation, best known for organizing Iraq’s pavilion at the Venice Biennale, is launching a new initiative. Called Ruya Maps, the project aims to support and show the work of artists who are largely “invisible” in the West because they live and work in the world’s conflict zones, according to Ruya’s founder Tamara Chalabi.

Ruya Maps will kick off with an inaugural exhibition in London’s Fitzrovia Chapel this fall. The show will feature the work of an artist not from Iraq or the Middle East, but another site of conflict: Venezuela. Pepe López created his large-scale installation Crisálida amid the country’s deep economic crisis and political instability. Venezuelans are struggling to cope with chronic shortages of basic goods and a currency, the bolivar, that is almost worthless. In late May, the inflation rate reached 25,000 percent.

Before its inaugural show is even open, however, Chalabi already has bigger plans for Ruya Maps. “We are looking to pop up in other locations, not just in London,” she tells artnet News. The dream, she says, is to open a permanent space in the West that complements Ruya’s space in Baghdad.

Pepe López, detail of Crisálida, (2017). Photo by Julio Osorio. Copyright the artist, courtesy Ruya Maps.

For Ruya Maps’s first installation, López has wrapped around 200 possessions from his home in Caracas—including a car, a motorcycle, books, and a piano—in polythene film. He also wrapped himself. “Plastic was one of the few materials he could find. Wrapping every object is almost like embalming them,” Chalabi says. She notes that artists can “feel the same sense of loss and hopelessness whether they come from Syria, Kashmir, or Venezuela.”

Chalabi was partly motivated to launch Ruya’s international expansion after witnessing what happened to the Iraqi artists who participated in the Venice Biennale after they returned home. Although they had raised their profiles significantly by showing alongside the likes of Ai Weiwei and Francis Alÿs, opportunities remained limited because there is no art market in Iraq, “So, there is no chance for any of the artists to have a future as an artist,” Chalabi notes. “Unless they leave, and to leave you have to leave as a refugee or an illegal immigrant.”

As an example, Chalabi cites the sculptor and painter Hashem Taeeh, who is based in Basra, an Iraqi city that has seen widespread rioting recently. He took part in the Iraq Pavilion in 2013 as part of the collective WAMI. “Basra had this romantic reputation as the Venice of the East,” Chalabi says. Now, there are water shortages and power cuts in addition to high unemployment, which sparked rioting in the oil-rich region of southern Iraq last week.

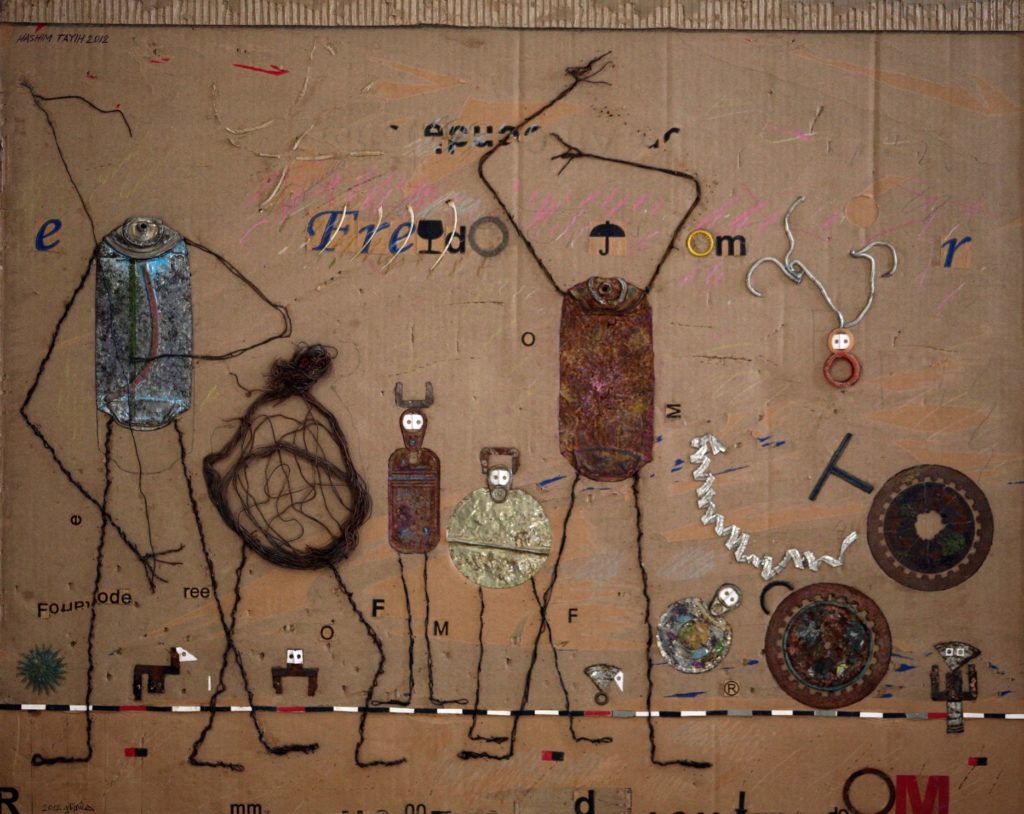

Hashem Taeeh, Untitled (2014). Image courtesy of the artist and Ruya Foundation.

Taeeh creates large-scale drawings using crayons and felt-tip pens or old cardboard and waste paper. Recent works “communicate this feeling of doomsday scenario of people dreaming of water,” she says. His work is about his hometown, but also “about a bigger issue facing the world today.”

Iraq was initially included as part of President Trump’s travel ban targeting mainly Muslim countries, only to be removed after lobbying. (Venezuela remains on the list.)

But Chalabi says the US is not the only country that has barriers in place that make it difficult for Iraqi artists to travel freely. “I know artists from Iraq who have not been able to set foot in Britain for years,” she says. “They are just not given a visa because of their age and because they fit the profile of an asylum seeker. The travel ban is terrible, but the lack of hope is worse.”

Ruya Maps is an attempt to give international exposure to talented artists who are denied it “because of where they come from,” she says. At the moment, for artists who are outside the commercial or the nonprofit art worlds in the West, it is as if “you don’t exist.”

“Pepe López: Crisálida,” is on view from October 14 through October 26 at the Fitzrovia Chapel in London.