Art World

MoMA’s Union Employees Have Been Working Without a Contract for Nearly Two Months—and Negotiations Have Stalled

If MoMA doesn't improve its contract offering, a strike could be in the offing.

If MoMA doesn't improve its contract offering, a strike could be in the offing.

Sarah Cascone

Negotiations are dragging on at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, where the contract for MoMA Local 2110, which covers some 260 museum employees, expired on May 20 without a new one in place. At issue are staff concerns about wage increases, medical costs, job security, and the increasing demands of executing the museum’s latest expansion. Should the two sides be unable to reach an agreement, the union could vote to go on strike.

“The aim, of course, is to prevent that,” Daniel Fermon, an associate librarian at the museum and the unit chair of MoMA’s union chapter, told artnet News. But don’t expect the union to back down from their demands anytime soon. “I think there is a lot of anger,” he said.

After months of negotiations, MoMA, meanwhile, remains optimistic about the situation. “We continue to make progress with Local 2110 at the bargaining table,” a museum representative told artnet News in an email. “It’s been a productive process and we’re confident we’ll arrive at an amicable resolution as we have during prior negotiations with Local 2110 and our four other unions.”

Fermon had a different view. “We are still far apart,” he said. “They’re lowballing us.”

MoMA Local 2110, also referred to as PASTA (the Professional and Administrative Staff Association of the Museum of Modern Art) is a white-collar chapter of the United Auto Workers Union.

The contract negotiation comes at a time when MoMA is making the final push on a massive expansion plan that will see 50,000 square feet in new gallery space unveiled in 2019. One of the union’s main alleged grievances is that the museum is looking to offer them less even as the institution demands more of the staff in the run-up to the opening.

“We don’t get compensated overtime for most of our employees,” Fermon said. “It’s galling given all the extra work that we’re doing these days for the institution which we work for and love.”

According to the union, MoMA’s proposed contract eliminates step increases, which have been in place for over 20 years. Currently, after three, six, and nine years in the same position, union employees are entitled to make a respective five, 10, and 15 percent above the minimum salaries for their title. MoMA originally proposed doing away with step increases altogether; their most recent offer would eliminate step increases for all new employees and for those making over $60,000, and reducing step amounts for everyone else, Fermon said.

Another point of contention is healthcare. The union is looking to expand health reimbursement accounts to all union members. The museum currently offers up to $800 for families and $400 for individuals for the lowest paid union employees, half that for mid-tier salary ranges, and no benefits for those making above $75,000. The union wants all members to receive fully funded health reimbursement accounts, but “they are simply saying no,” said Fermon.

The union also wants to change the rules surrounding curatorial assistants, who are the only members of the union who can be fired without cause. “They usually just explain to curatorial assistants that they’re only going to be hired for four years,” Fermon said. “The museum wants to treat curatorial assistants like fellowships, but they are more like regular curatorial staff who put up the exhibitions and everything else.”

Ahead of the upcoming expansion, MoMA is also looking to change its policy toward temporary workers, who can currently only be hired for six months at a time, according to Fermon. Museum leadership would now like to hire temps—who receive no benefits and are more traditionally used to staff the book shop and visitor services on a seasonal basis—for up to a year. Fermon called the proposed change to the contract “a continuation of the museum’s reliance on temporary employees.”

Fermon, who has worked at MoMA since 1971, was also part of the union’s negotiating committee back in 2000 when workers went on strike for 134 days. As a result of that walk out, MoMA agreed to expand the union to include more of its staff. The union’s 2015 contract saw several protests before the two sides reached a compromise.

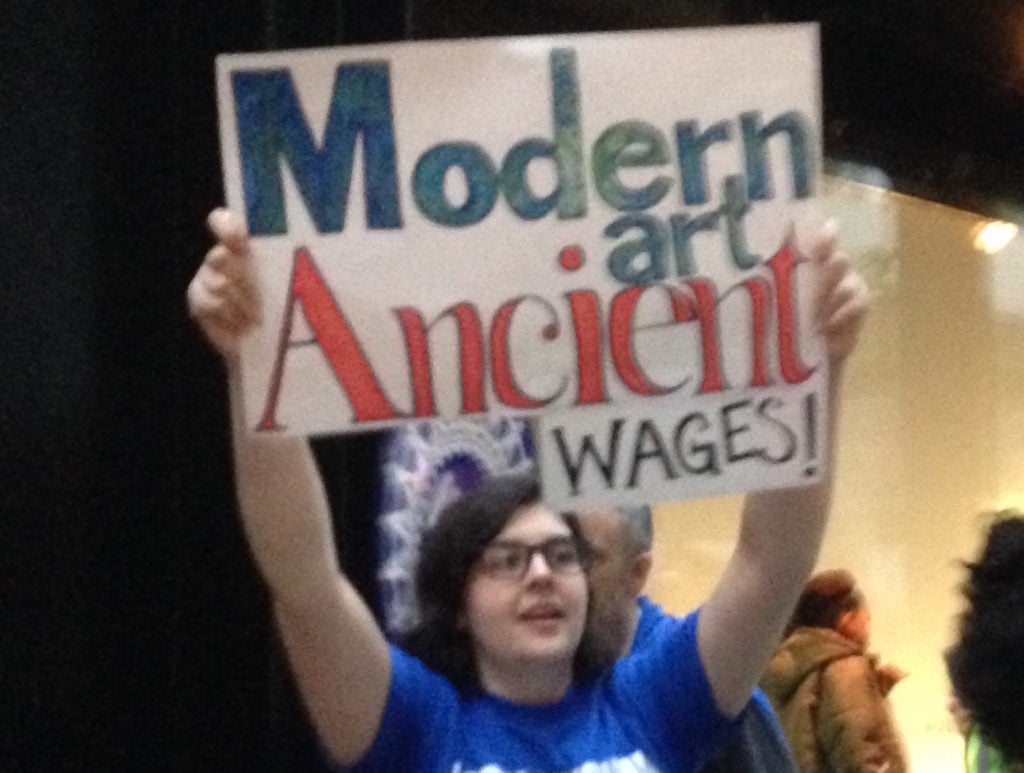

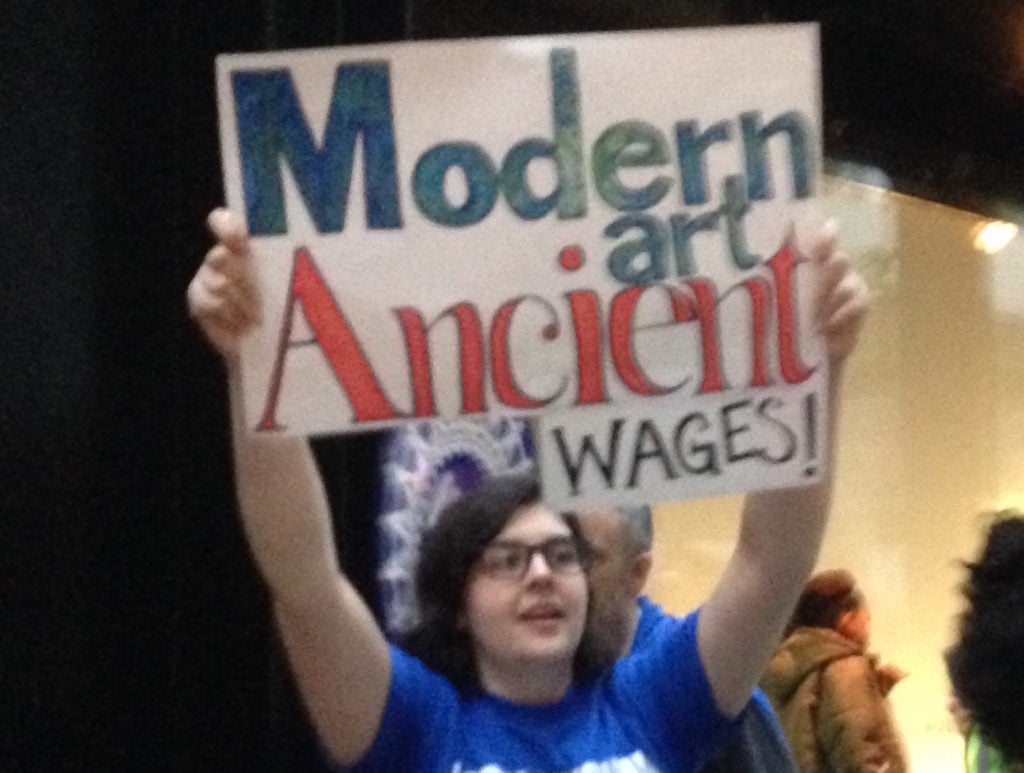

The current negotiations have been marked by high-profile actions from union members, who wore union shirts to a recent staff picnic and picketed outside the museum as well-heeled guests arrived at the annual Party in the Garden, a fancy fundraising event that featured a performance by St. Vincent.

Last week, staff members handed out flyers at the opening of “Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980,” quoting the exhibition’s introductory text, which touts “architecture’s potential for social engagement and transformation.” The leaflet contrasts this “progressive statement” with what it called the museum’s refusal “agree to a fair contract for its workers.”

Fermon insists that the union’s demands are reasonable. “We’re not firebrands,” he said, pointing out that “there’s a remarkable unity” across all departments and salary levels in the bargaining unit.

MoMA declined to comment on any of the specifics of the contract negotiations, but reiterated an earlier statement, noting that “MoMA’s extraordinary staff are the best in the world and we are committed to reaching a contract with Local 2110 reflecting that.”

“People are overworked and underpaid and they know it,” Fermon fired back. “It’s not enough to tell us how much we’re loved or whatever. There needs to be an appropriate fair response from the museum in terms of a contract… it’s time for them to step up to the plate.”