On View

See 6 Highlights From a New Show on the Global Footprint of Yiddish Culture—From Avant-Garde Puppets to Cubist Book Covers

The new exhibition at the Yiddish Book Center brings together objects spanning 150 years of Yiddish life and culture.

The new exhibition at the Yiddish Book Center brings together objects spanning 150 years of Yiddish life and culture.

Richard Whiddington

The Yiddish Book Center is something of a misnomer. The Amherst, Massachusetts, institution runs language classes, trains translators, produces podcasts, hosts the summer music festival Yidstock, and will soon open the world’s first museum spotlighting Yiddish culture. But yes, it has books too: more than a million have been salvaged since its beginning as a pet project of energetic grad student Aaron Lansky.

“Yiddish: A Global Culture,” its new core exhibition that was five years in the making, has seen curators scour the archives and tie together donations that have arrived over the past four decades from around the world. The result is a peripatetic tour of Yiddish culture over the past 150 years and a poignant reminder of its diminished status in today’s popular consciousness.

One hundred years ago, you would be hard pressed to wander through downtown New York, Berlin, or Buenos Aires without encountering some marker of Yiddish life. Walls were plastered with theater show posters, newsstands stocked with daily papers, shops announced their wares with bilingual signs. Yiddish culture was, as the show’s lead curator David Mazower put it, a natural part of the urban landscape. The Holocaust and the ensuing speed with which Jews assimilated in the postwar period, losing their language in the process, has rendered the former prominence of Yiddish culture forgotten.

Through more than 350 cultural artifacts, this exhibition seeks to make this history visible again and dispel some misconceptions in the process.

“For the general public, I think it’s more about a lack of knowledge: Yiddish maybe means Fiddler on the Roof,” Mazower said. “For Jews, it’s a different story. Sadly, many Jews have internalized age-old stereotypes about Yiddish—that it’s a jargon without a proper grammar and that it doesn’t really have a culture worth speaking about.”

In “Yiddish: A Global Culture,” we meet writers, renegade philosophers, weavers, poets, avant-garde puppeteers, playwrights, and many more besides. The culture they carry spans the globe, comprising an informal network dotting from Cuba to China and from Lotz to the Lower East Side. In each we catch a glimpse of the world they inhabited and a sense that this is a culture as vibrant and idiosyncratic as any other.

Here are six objects that bring that culture to life at “Yiddish: A Global Culture.”

Detail from Yiddishland by Martin Haake. Courtesy Yiddish Book Center.

The first artwork visitors encounter at the Yiddish Book Center is Yiddishland, a 60-foot mural by Berlin-based illustrator Martin Haake. Influenced by children’s books of the 1950s, Haake’s works are flat, bright, and playful. Maps are a format Haake has repeatedly returned to and this sits well with the mission of “Yiddish: A Global Culture”: to spotlight the breadth of the Yiddish diaspora. Yiddishland succeeds presenting a globetrotting tour of Yiddish life over the past century.

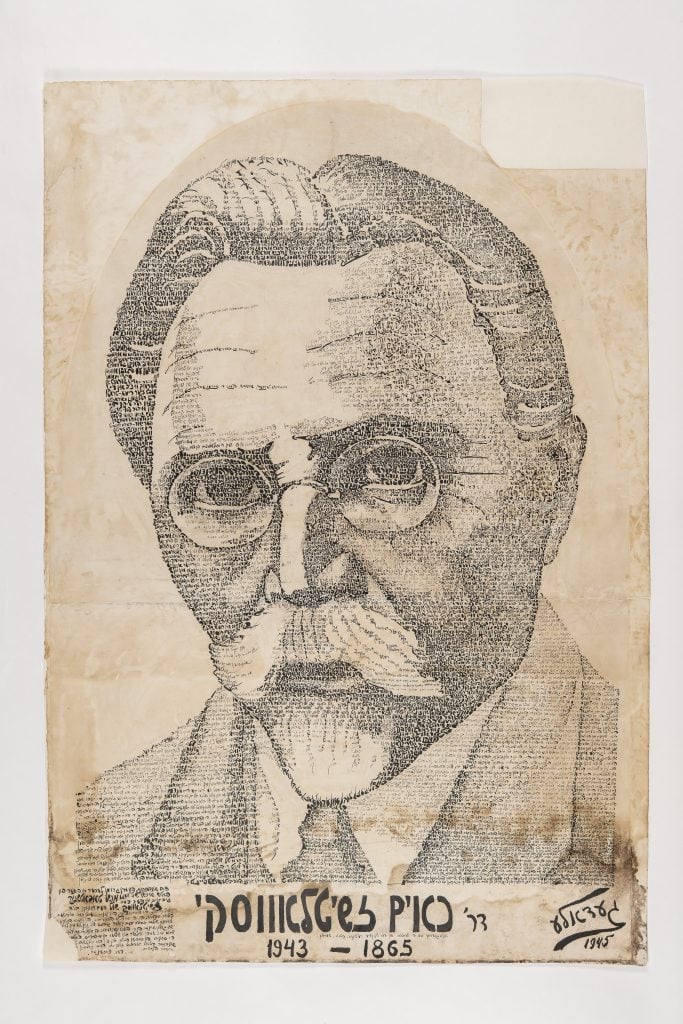

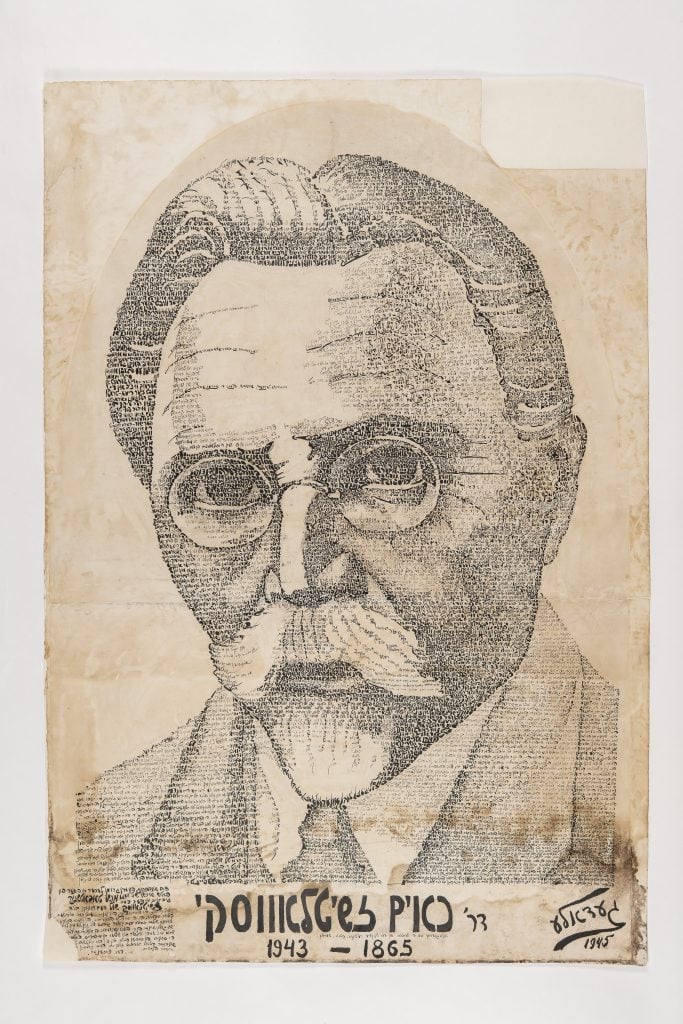

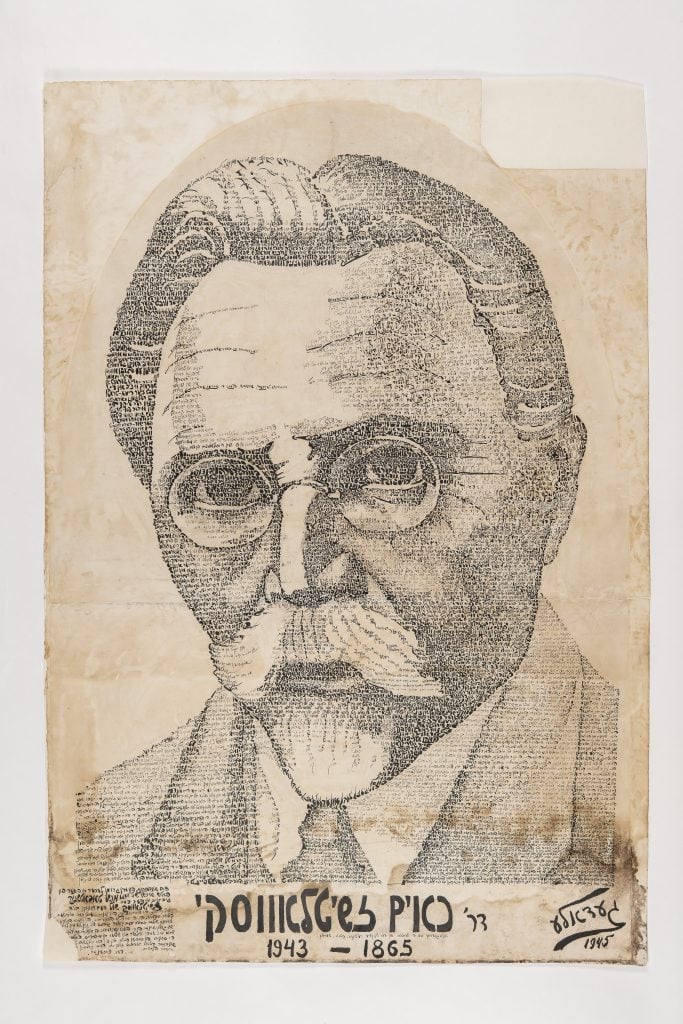

The micrograph was created by self-taught artist Guedale Tenenbaum. Courtesy Yiddish Book Center.

Few championed the revitalization of Yiddish culture with greater fervor than Chaim Zhitlowsky. His many writings and tours across the Yiddish diaspora turned him into something of an icon, albeit a provocative one. Such status is evident in this portrait made by Guedale Tenenbaum, an immigrant textile weaver in Argentina, two years after the activist’s death in 1943. Composed of thousands of Hebrew letters, it hanged inside the Zhitlowsky School in Buenos Aires until its closure. It was discovered torn in half on the street and has only recently been cleaned, restored, and framed by the Yiddish Book Center.

A pair of Modicut puppets. Courtesy Yiddish Book Center.

The story of happenstance that connected puppeteers Zuni Maud and Yosl Cutler is a film waiting to be written. They met as satirical illustrators in 1920s New York and fell into puppeteering after the puppets they’d been commissioned to make were rejected. They duly wrote some scripts and opened a theater called Modicut inside an old clothing factory. The duo was a hit and set out on global tour, nearly parking their act in the Soviet Union where in 1932 they were asked to launch a Yiddish puppet theater collective. A year later, the two fell out never to perform together again, with Cutler killed by a drunk driver in 1935. Here, the Yiddish Book Center offers puppets from their avant-garde theater.

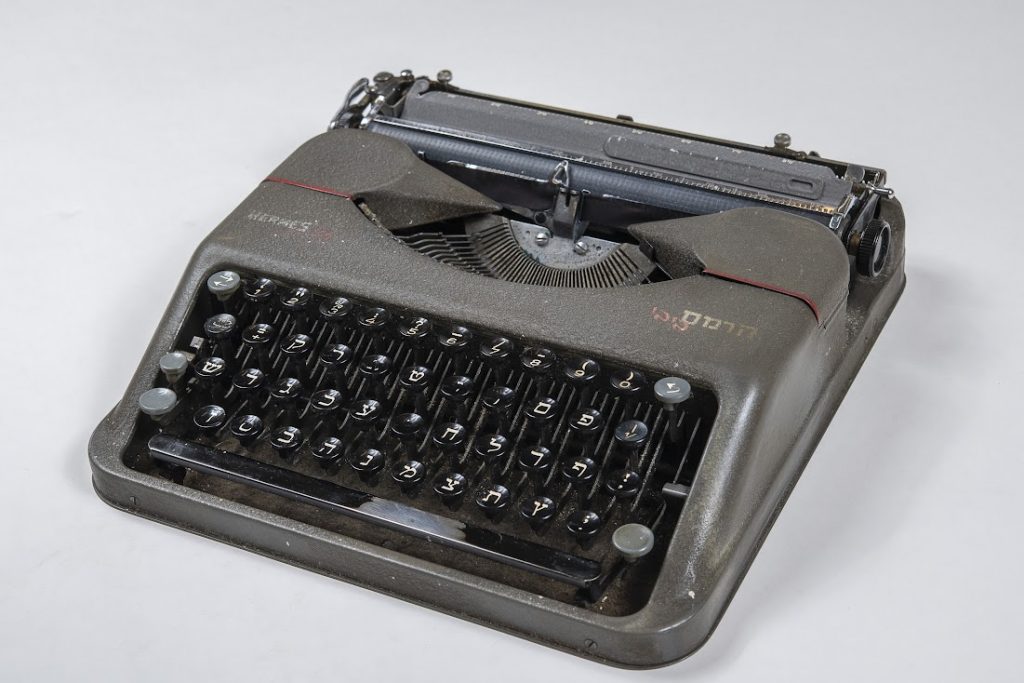

The Hermes Baby owned by Chava Rosenfarb. Courtesy Yiddish Book Center.

The Yiddish Book Center is the proud steward of the largest collection of Yiddish typewriters (45 and counting). Among them is Rosenfarb’s Hermes Baby, widely considered one of the most practical and portable models ever designed. Rosenfarb, a Polish émigré who moved to Canada in 1950, wrote extensively about her experiences in the Holocaust—she survived both Auschwitz and Bergen Belsen—and is considered a seminal figure in post-war Yiddish literature.

A medicine ball owned by Sholem Asch. Courtesy Yiddish Book Center.

A member of the Warsaw literati in the 1900s, Sholem Asch was a totemic and divisive figure of 20th-century Yiddish literature. God of Vengeance, his play set in a Jewish brothel, stirred controversy most everywhere it was staged, most notably in New York where it provoked an obscenity lawsuit in 1923. After relocating to the U.S. in the 1930s, Asch was hounded out of the country by the toxic climate of McCarthyism. One of his less polarizing pursuits was exercising. From his home in Stamford, Connecticut, he enjoyed swimming, horse riding, and working out, such as with this leather medicine ball.

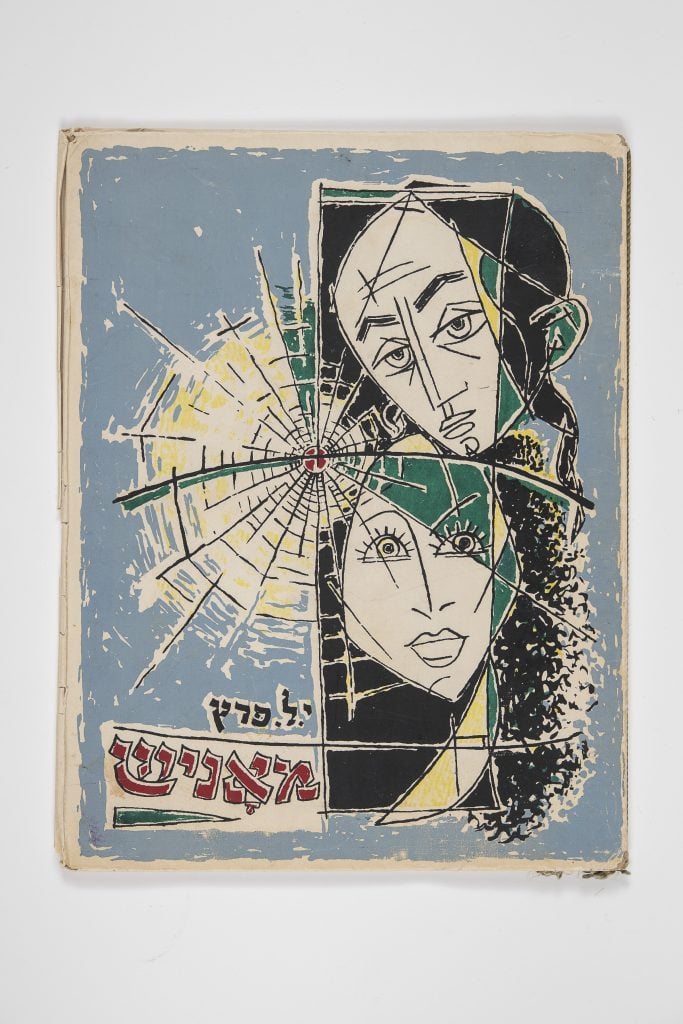

Peretz is considered a transformative figure in Yiddish literature. Image: courtesy Yiddish Book Center.

The influence of Paris’s Cubism movement is evident in Shaar’s composition. And indeed after surviving a death camp outside his native Lotz, Poland, Shaar completed his artistic training in the French capital before becoming a celebrated illustrator of Hebrew literature. In 1952, he produced a limited-edition cover for Monish, a narrative poem about the seduction of a young student written by I.L. Peretz, who, incidentally, had been an early mentor to the aforementioned Asch.

“Yiddish: A Global Culture” is on view at the Yiddish Book Center, 1021 West Street, Amherst, Massachusetts.

More Trending Stories:

Four ‘Excellently Preserved’ Ancient Roman Swords Have Been Found in the Judean Desert