Art World

Can Art Help Combat Climate Change? A Q&A With Shanghai Project Co-Founder Yongwoo Lee

With the planet's ecological plight becoming starker every day, the veteran curator believes art can play a role in our survival.

With the planet's ecological plight becoming starker every day, the veteran curator believes art can play a role in our survival.

Andrew Goldstein

Can art change the world? It’s a question debated nightly in dorm rooms around the world, but in the professional art world such ambitions can easily be eroded, chipped away by the allures of the gleaming cultural machine that renders artworks little more than luxury objects. Idealism does rear its head from time to time, however. Such is the case right now in Shanghai, where an improbably high-reaching hybrid event called the Shanghai Project is coming to its conclusion.

The initiative is the brainchild of two people: Yongwoo Lee, the Seoul-born founder of the Gwangju Biennial in South Korea and currently the director of the Shanghai Himalayas Museum; and the globetrotting curator Hans Ulrich Obrist. It was initiated last September with a round of conferences in which artists came together with technologists, practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine, social scientists, and ecologists to ruminate about the deadly perils posed by climate change.

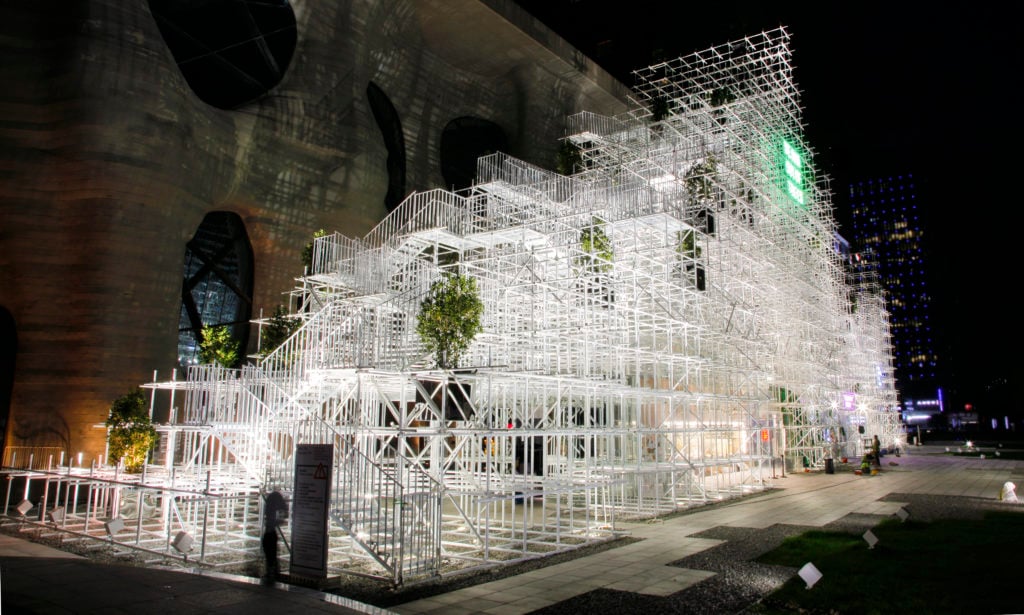

Given the overall theme “Envision 2116,” the gathered intellectuals were asked to project themselves 100 years into the future—when forecasts predict that Shanghai will be largely submerged by rising tides—and develop a response to the global crisis. As a forum for their discussions, the architect Sou Fujimoto created a modular Envision Pavilion, consisting of a skeleton of interconnecting white tubes festooned with green plants, a mixture of the natural and the manmade.

Sou Fujimoto’s Envision Pavilion. Courtesy of the Shanghai Project.

The September colloquium resulted, this April, in an exhibition at the Himalayas Museum in which the project’s “Root Researchers”—including the artists Maya Lin, Qiu Anxiong, Otobong Nkanga, Gustav Metzger, Etel Adnan, Ian Cheng, and Yoko Ono; the architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro and Li Naihan; and the environmental scientists Thomas Hartung, Jennifer Jacquet, and the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists—presented a group of paintings, installations, films, and performances.

The profusion of various efforts fills two floors of the museum, with a wide range of projects: Yu Hong contributed a large vertical painting of figures taking refuge on an electrical pole from rising tides below; Liam Gillick installed a parked Volkswagen, doors open; and Sophia Al-Maria offered a multimedia performance that produced a series of offerings “intended to future-proof and bless 2116;” Shanghai-based McKinsey managing partner Zhang Haimeng contributed a smartphone game that allows you to “invest” in futuristic businesses; Maya Lin supplied “What Is Missing? Empty Room,” and darkened-room installation that provides visitors with screens that glow with interactive images of extinct animals, as a memorial for the Earth’s vanishing species.

This weekend, on July 16th, Hans Ulrich Obrist will conclude the show’s run with a set of his signature “marathon” interviews, conversing with 16 of the project’s participants in succession inside the Envision Pavilion. To find out more about the thinking behind the Shanghai Project and its variegated ambitions, artnet News’s editor-in-chief Andrew Goldstein spoke to Yongwoo Lee about his vision.

How did the idea for the Shanghai Project first arise?

I have been involved with art biennales for over 20 years, and over this time I have tried to extend the notion of art exhibitions quite radically by involving socio-political subjects in ways that revolt against existing exhibition culture. In fact, I have not been doing visual-art exhibitions but have instead been trying to integrate many disciplines. So, with the Shanghai Project, I wanted to create an intersection of many different disciplines as a kind of melting pot, and to also bring different fields together in the context of China.

As you know, there is far less of an NGO movement in China compared to Western societies, and there are fewer civic activities. I thought what we need is a participatory platform where people can exchange ideas and make connections in the fields of art and culture, but also communicate with general consumers of culture and even scientific researchers. In a way, I was thinking of two different possibilities: one, that the Shanghai Project should engage with the foundations of Shanghai and its citizens; and, two, that it should be a platform where people can really try to get together.

Simply put, getting together is not that usual in China.

A roundtable discussion in the Envision Pavilion. Courtesy of the Shanghai Project.

You mean gathering people together in one place?

I don’t mean physically, but with their consciousnesses, and with their own articulation of viewpoints. I’m not saying China is a controlled society, but compared to New York—or America, generally speaking—that kind of participatory platform is lacking. So, in a way, I wanted to create a sort of social media, which is a very different concept than an exhibition. I also wanted it to play the part of a participatory NGO.

Was there any event, or any other kind of prompt, that made you feel there was a need for that kind of platform?

As a visual-art curator who has been trying to integrate different fields of research, I’ve always wanted to create a model of convergence that shows just how wide the spectrum is. As you know, there are a lot of areas of scientific research—such as in artificial intelligence, virtual realities, and even traditional Chinese medicine—that pose major questions for the visual arts today in the broader context.

I also try to mix in elements of agriculture, ecology, extinctions, and climate change, which is a very, very important issue in China today. Nothing is as important an issue in China today as sustainability, due to the increase of CO2 and greenhouse gas, and also rising water levels.

When I first heard about the risk in China, I learned the metropolitan part of Shanghai will be submerged in less than a century’s time if no action is taken. That is why it’s so important that the Shanghai Project be a platform where people can come together and discuss imminent problems, not only when it comes to Shanghai but also the other coastal giants like Hong Kong, Mumbai, Tokyo, London, New York, and Sydney. They all face the same problem. Its about extinction, really.

It’s clear that climate change is an existential crisis. Considering its vital importance, why is art the right context to engage with its challenges? How can activities in a museum or a biennial or any other art terrain usefully address these issues?

I have no intention to create sites just for art consumers—but it’s worth asking, who are the art consumers today? One person might say it’s the collectors, but I think the final consumer of art is not the collector and not even the museum audience, but the general public. Are they just a passive audience, who need to be educated by the expert? I don’t think so.

Art should be able to meet the general public where they live, and it should be able to understand the feedback of the general public, to listen to their voice. In a way, art should be a voice of the public. Otherwise, it will never be able to reach a large audience.

Going through this year’s Shanghai Project, one of the most affecting works was Exit, a 45-minute-long video installation by the poet Paul Virilio and architecture firm Diller, Scofidio + Renfro that vividly charted trends in deforestation around the world and the disappearance of native languages, using audio and data visualization to make the loss hauntingly apparent. When it comes to artists tackling serious issues, this kind of data visualization can be a very effective rhetorical method for getting an idea across. What are other ways that artists can productively tackle big real-world problems, that don’t amount to merely aestheticizing them?

Artists can do data visualization exquisitely, of course, but I believe art also has an ability to connect emotionally with civic society. As I said, the pessimistic scientific data proves that Shanghai will be sunken in less than half century. But there is no artistic data yet that has the power, or the ability, to emotionally access civic society—and this is very important, because art can create social narratives that have a healing effect.

“EXIT,” Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Mark Hansen, Laura Kurgan, Ben Rubin, in collaboration with Robert Gerard Pietrusko and Stewart Smith. Idea by Paul Virilio. Animated image projection, 45′, 2008-2015, Collection Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris. View of the installation EXIT, Photo © Luc Boegly.

Art typically reaches a very exclusive group of consumers today, but, art-historically speaking, if you go back to the Renaissance period, art was fluently communicating with every society, from the scientific community to the military to regular people. Art should reclaim this broader context, so it can unfold its own creative criteria to the larger public.

To go back to the Shanghai Project’s ecological theme, it’s interesting to consider the larger context of the show. As the United State is withdrawing from the battle against climate change and the search for renewable energy resources, China is doubling down on this sector as both a potentially huge economic driver and as a place where they can assume the mantle of global leadership. Part of China’s goal is to make non-fossil fuels 20 percent of the country’s energy consumption by 2030, which has led to massive subsidies to the wind and solar power industry. One of these companies, Envision Energy, is a sponsor of this show. What role does art play in this broader move toward sustainable energy in China?

China has experienced an extraordinary growth in industrial developments over the last 30 years, but the country has also experienced the difficulties of climate change. China is the number one producer of CO2 and greenhouse gases in the world, ahead of the US and India, so the Chinese government understands the social urgency and has started many new initiatives, such as building green buildings that use less tap water and electricity—things like that. Art is not isolated from these campaigns.

The idea of a “campaign” is very important. Chinese people understand that campaigns originate in the government, but they have never experienced a “campaign” coming from civil society, or from social media. When it comes to ecological urgency, the drive is coming from both sides now.

I never intended to invite one of these environmental companies to be a lead sponsor—it just happened like that. Fortunately, the CEO has a full understanding of what’s happening globally, and he’s a real visionary guy—someone who is selling sun and wind. He’s the one who suggested discussing extinction issues, because he says that the city of Shanghai has almost no hope of surviving in a century’s time if we keep producing the levels of CO2 and greenhouse gases. We really need action.

He said he wanted to support art that can be like an antenna to broadcast a campaign of action that can reach the general public. Now I’m even thinking of making chapter three of the project a collaboration with more organic energy companies, like solar and wind energies.

It would seem that an ecological theme would be very useful for artists in China today for several reasons. There’s a tendency that when artists go against the interests of the Chinese government, such as with activist political art, they meet harsh barriers, if not reprisals. Overtly commercial or technologically futuristic art has an easier time getting prominently embraced, such as with Adrian Cheng’s K11 Foundation, in part because it conveys a positive message about economic strength, luxury consumerism, and technical prowess that seems to be encouraged by the government—though, of course, this kind of art doesn’t have the most progressive narrative.

When it comes to climate change, this is a progressive issue that has been embraced by the Chinese government. Forgive me if I’m mischaracterizing this, but this confluence of forces would seem to make climate change a very beneficial theme for Chinese artists to explore.

Well, if you look at the history of contemporary art in China that starts right after the Cultural Revolution, it’s remarkable—you see political Pop that appeared in 1978-9, which was a real, substantial avant-garde movement in China’s contemporary art, led by artists who had experienced the upheavals of the Cultural Revolution. Then, since the 1980s, China’s contemporary art has been really boomed, with a lot of the private museums coming out in recent decades.

But there is a kind of misunderstanding of China’s contemporary art in Western society. They see China as a huge market, with tons of museums coming out—something like 100 a year. But, while that might be close to the truth in terms of numbers, there are not many real collectors who understand the artists, the audience, and the institutions all together.

There are a lot of nouveau riche, of course, and they have a strong will to develop cultural institutions—like music halls—and also to link their businesses to these artistic institutions, but they lack professionalism. Also, while the Chinese have a long history and a very thorough understanding about the nature of their culture, there is not much open critical discussion because they had to go through a difficult period politically. They’re not very talkative, and while they are thoughtful, they don’t criticize others. You have to look beneath the surface to find the true and lively mixture of voices.

Compared to Western society, this is something very different. So you can’t really apply the different standards of the West to China. For instance, when you talk about Chinese modernism—and modernism is a key issue, philosophically—it follows the country’s industrialization that only started in the 1970s and ‘80s. But, at the same time, most of the theorists and researchers here tend to be applying all sorts of Western tools to Chinese issues directly. And context is very important in order to understand the creative forces in China.

With the Shanghai Project, you have to understand Shanghai, which is one of the largest and fastest-growing cities in the world, with a population that’s very close to 30 million. So, to connect with the audience in this city, the Shanghai Project has tried to represent the historical, cultural, social, and political context surrounding it, and to use art to reframe these issues and tie them together—history, literature, culture—to create something new. It’s an integrated, hybridized model of exhibition, not just visual art.

In fact, for the first chapter, we decided to focus exclusively on problems facing the public, with no exhibitions at all—that would only come in the second chapter—because, strategically, we wanted to create political distance from traditional visual-art exhibitions.

Li Naihan, Mind Palace, virtual reality experience and installation (2017). Courtesy of the researcher.

How did you manage to do that?

For this first part, we created a community-participation program where we could build a sense of familiarity around the Shanghai Project for the general public. There are many empty, abandoned buildings that were left over after the radical period of industrialization and modernization, so we decided to refurbish one to make it a gathering area for citizens, with a small teahouse and a small participatory gallery space.

This helped people start to realize the nature of the Shanghai Project—to think, “Oh, they are very close to us.” People are nostalgic about those abandoned buildings, with their cement blocks, and have missed those remnants of cultural history. So by creating our space there we tried to tie those things together emotionally for the citizens.

Then we started public programming to reach out to people, including the younger generation, which is very important not just as future consumers but as the future of China. This younger generation that is part of a particular cohort, the jiulinghou [the generation born in the ‘90s], is very different, compared to the older generations—they are a newly born generation, and we want to bring them into what we’re doing.

From the beginning, we declared that this will be a citizen-oriented, audience-oriented cultural program, like a large-format cultural emporium, not for shopping but for consuming ideas. We first thought of the Shanghai Project as a kind of multidisciplinary knowledge platform, but later I changed that to an “ideas” platform. Knowledge is kind of static, whereas ideas are much more mobilizing—it’s thinking in motion. The true nature of the Shanghai Project is as an ideas platform.

It’s funny you say that, because I was just at the Yuz Museum, where crowds of young people—we call them “millennials”—were paying about $20 to go see the KAWS show there. KAWS, of course, is very stylish, it’s a little bit edgy, it comes from street culture and pop culture, it’s bright and cool, but it has no substantive ideas. It’s pure consumerism in the classic sense, with the show culminating in a display of KAWS’s popular line of collectible figurines. Then I went to the K11 Art Foundation, which is in the basement of an art-themed luxury shopping center, where a show of attitudinal, Post-Internet art inhabited the same sleek wavelength, as if it were a Gucci ad campaign. Do you think this yoking of art to consumerism—which so often strips out the ideas, let alone knowledge, in favor of attitude—is a risky phenomenon?

Well, what characterizes the KAWS exhibition is surface images of all different cultures—I’m not saying superficial images—which fascinates the viewing public, especially the younger generation. But then they also go to the James Turrell show at the Long Museum, which is the other show with an American artist here, and it’s something very different compared to KAWS. And then there is the Shanghai Project, which is very different once again.

I don’t think any of this is a problem. Chinese people are very open to all kind of cultures. Some might try to tame those new trends, but if you take a closer look at Chinese contemporary art so far, over the past 30 years, you can find a very distinct and particular “Chinese-ness” within it. It doesn’t mean that it has been excluding the culture of other societies, but the Chinese have been able to create their own languages and grammars so far, which is very important for them.

Many of them understand Western culture and are fascinated by it—so of course the James Turrell and the KAWS shows are doing very well here. In a way, they are fully aware of what is going on around the world, so it’s really about diversity in China. Shanghai, in particular, is like a gateway. It’s a port city that for a long time has been open to external cities as the economic center of China—it’s the New York of Asia.

An installation view of the Shanghai Project exhibition. Courtesy of the Shanghai Project.

Considering this artistic climate, with so much commercialism intermixed with art that carries more ambitious ideas, is it possible for something like the Shanghai Project to make sure that its message gets through to the broader public?

I don’t think that art has an answer, and it doesn’t try to produce answers. It produces suggestions—sometimes direct and sometimes indirect suggestions to society. The art is never the political or social campaign itself, so it’s not our role to give the answer to the audience, to the citizens. But we do have a very strong suggestion in the name of artistic practice.

It’s about envisioning alternatives.

Exactly.

It’s worth belaboring the point, to say that overtly commercial, art-as-luxury art doesn’t envision an alternative—it actually celebrates the status quo. To promote art that does create a map toward alternatives, particularly when it comes to such a massive issue as climate change, seems to be a worthwhile pursuit.

Well, there is a heavy burden, as a curator, as an academic, in this moment of contemporary art, because there is little real criticism that exists anymore. People say that it has vanished, disappeared, but I don’t believe that. People are buying a lot of art-fair art, and that can include critical context in it, but it starts to lose its own flavor in the marketplace.

I’m against that. There has been criticism present within art in China over the last 20 to 30 years. But now capital is the center, and the market is the central issue. If you look at museums today, the marketing department can be bigger than the curatorial department. This reflects the spirit of contemporary art today. I certainly believe that we need to recover our spirit. We have to come back to art.