Buyer's Guide

7 Questions About the Artistic Potential of Plants With Painter Soimadou Ibrahim and Advisor Lisa Schiff

Ibrahim's solo exhibition "For Life is Not Eternal" recently opened at Schiff's SFA Advisory in New York.

Ibrahim's solo exhibition "For Life is Not Eternal" recently opened at Schiff's SFA Advisory in New York.

Artnet Gallery Network

In his current solo exhibition “For Life is Not Eternal” at New York’s SFA Advisory, London-based artist Soimadou Ibrahim elevates the household plant to a new heightened position.

His paintings have more typically figured on imagery of his family members painted from memory or photographs, but while in quarantine, Ibrahim found himself drawn to domesticated flora, both as quietly living beings and as a metaphor for these very family and friends.

Soimadou Ibrahim at work in his studio. Courtesy of the artist.

In these images, Ibrahim imbues his plants with the same dignity and attention as he does his figures. The Musa species—more commonly known as banana trees—plays a particularly central role. The species, which originated in Asia, was carried across to the artist’s native Comoros in waves of immigration of Bantu, Austronesians, Arabs, Somalis, and Indian peoples to the region. Much as the culture of Comoros changed with the introductions of these peoples, so did the Musa species undergo new mutations. For Ibrahim, the species has become indicative of diaspora and his own move from Comoros, then to France and the U.K.

Lisa Schiff, the founder of SFA Advisory, found herself particularly intrigued by these paintings in the wake of quarantine. Recently. we spoke with Ibrahim and Schiff about the new exhibition and what it’s been like working together.

Lisa Schiff, 2021.

Lisa, where did you first encounter Soimadou’s work, and what struck you about it?

LS: I bought a small painting by Soimadou from his show “My Thoughts Tell Me Tales” at ATM Gallery over the summer. That was his first solo exhibition in New York. It was the only work that was just a small plant and when I received it in person I was blown away by the surface and colors. I knew immediately I wanted to work with Soimadou and invited him to present a solo exhibition at my Tribeca outpost, SFA Advisory.

Soimadou, why did you shift toward more floral and vegetal imagery over the past year? How do these works relate to the exhibition title “For Life is Not Eternal”?

SI: To me, it’s not a shift at all. I’ve always been painting plants, I treat them the same way I would people. I give the artwork the same amount of time and the same respect—it’s very important. “For Life is Not Eternal” evokes the fragility and beauty that life can offer. It’s a metaphor; a plant grows and then eventually dies, like us. It’s also about changing the somber mood that is often associated with the loss of life. In Comoros, people deal with death very differently compared to in the West; life is celebrated and people rejoice as opposed to being sad.

Soimadou Ibrahim, Koko Mouniyati (2021). Courtesy of the artist and SFA Advisory.

What was the first work you made in this series? What was that process like?

SI: Koko Mouniyati. I like painting these big Musa leaves, almost floating in the emptiness—it’s figurative but in the meantime very abstract. These particular bananas trees are the ones from my grandmother’s garden. In reflection, painting them was almost a way of painting her. I will always remember seeing my grandmother weaving the banana leaves on her veranda, after having dried them, to make rugs.

Can you tell me about how the flora you have chosen to depict relates to your Comorian heritage?

SI: Most of the plants I paint are banana trees, or “Musa.” Musa is a very important part of Comoros culture; the bananas are a food source and the leaves can be used to make baskets, rugs, and other objects that can be sold at the market. The plant is also very abundant and does not discriminate—you can be rich or poor, but you’ll most likely have banana trees all over your garden. I’m just trying to pay homage to a plant that plays a significant role on such a small island.

In what ways are plants emblematic of diaspora?

SI: It’s part of your own culture, of what you know and what you’ve been taught. It’s the same thing for food or religion.

LS: I would imagine that whatever your memory is, either directly or through family members, you are drawn to certain things that carry the energy of place beyond its physical location. And I imagine that is different for everyone. Plants and Musa anchor Soimadou’s nostalgia for his ancestral homeland. Ironically, in this case, Musa is particularly interesting because they too in a way are members of their own diaspora—having been carried over from ancient Asia.

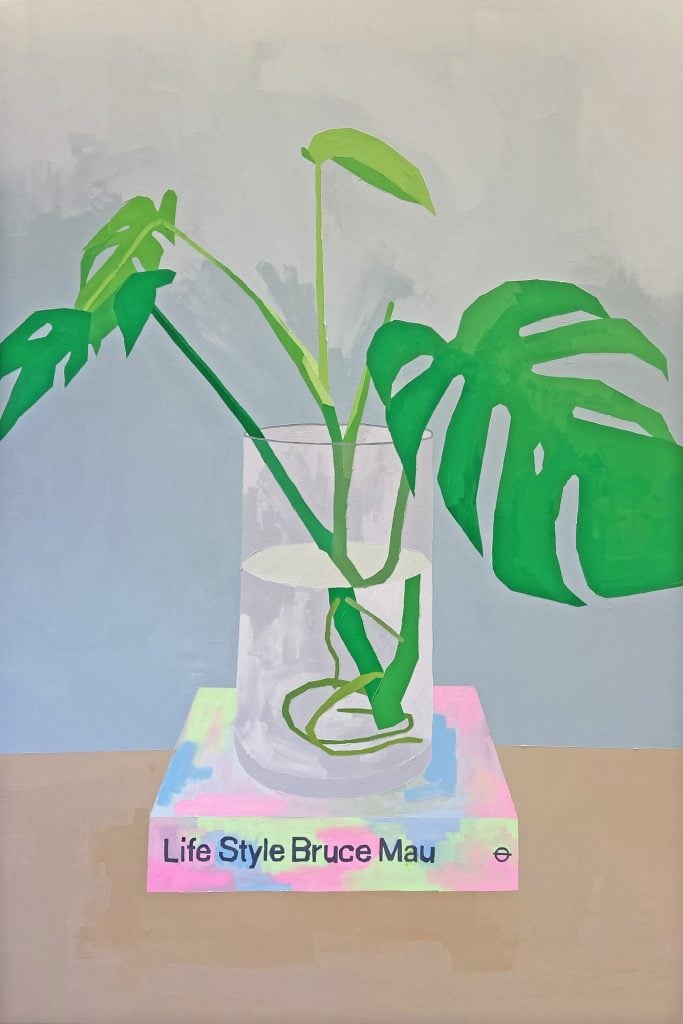

Soimadou Ibrahim, Bruce Mau (2021). Courtesy of the artist and SFA Advisory.

Lisa, why do you think this work is important? Why did you decide to organize this exhibition?

LS: I am having a nature situation thing as of late. As a city girl, nature is almost like something I would see at a zoo; I prefer it through the car window, slightly reified I guess. I am not proud of this, but am honest. Still, I am dedicated to bringing more nature to the zoo of the city. I was taken by Soimadou’s plants because I am surrounding myself with my own nostalgic world—like Soimadou. And I loved that most people gravitate towards his paintings with human figures whereas I found the fringes of lonely plants to be more interesting to me personally. While this is a personal description, I do think there is a general craving for nature the further we drift from it.

Do each of you have a favorite work in the exhibition?

LS: I do. I love Bruce Mau, not just for its reference to the famed designer, innovator, and educator, but for its graphic stillness, bold brushstrokes, and soft hues. I’m also very drawn to Cornish Colors for its matte, flat palette—a still life for a rainy day.

SI: The Butler. It represents the small joys in life with a young man holding a generous plate of rice to enjoy with family. In the meantime, the abundant banana leaves behind him are almost shaped like wings, which gives this sort of angelic-like impression and I like that.

“Soimadou Ibrahim: For Life is Not Eternal” is on view at SFA Advisory through December 17, 2021