As a result of the space race in the 1960s, NASA created some of the most iconic artworks of the 20th century in their quest to reach the moon. These ubiquitous images were printed on the covers of magazines and newspapers, featured on television, and even illustrated on postage stamps.

Now, “The Final Frontier: NASA Photographs From the 1960s,” live on Artnet Auctions through January 12, presents images that continue to spark curiosity and ignite our universal desire to explore the unknown. These rare to market, awe-inspiring photographs of space allude to scientific breakthroughs, the vastness of the universe, and the fragility of our own planet, while cementing their place in the history of both art and science.

It is impossible to view vintage NASA photography without acknowledging the intense political rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union that spurred the impressive technical innovation during the mid 20th century. The use of photography was crucial to NASA’s missions into space and the U.S.’s competition with the USSR. The technology for 70-millimeter film cameras, equivalent to the size of modern IMAX filming, was used by the department of defense to spy on the Soviet Union. For preparatory voyages into space, NASA eventually borrowed this technology to produce images of space.

In the early days of NASA, photography was minimally explored and underutilized. Given the weight requirements of traveling to and from Earth, camera equipment was viewed as unnecessary baggage, as the successful completion of a mission was prioritized over documentation or artistry. However, in the early 1960s, after the astronauts themselves advocated to allow cameras to accompany them into space, NASA appointed Richard Underwood as chief of photography. He became a staunch proponent of thoroughly photographing the lunar missions. Underwood taught the astronaut-turned-photographers how to frame their photographs and set exposures.

“Your key to immortality is in the quality of your photographs and nothing else,” he once told them.

Once NASA embraced the power of photography, the iconic Hasselblad camera became one of the most important tools onboard the lunar missions. In 1965, James McDivitt photographed fellow astronaut Ed White during the first spacewalk, with his camera at center stage in one of the most iconic images from the Gemini IV mission. The rigorous tests to become an astronaut, and to even be in the running for a spacewalk like White’s, are widely known, but few consider the benchmarks set for their cameras.

Ordinary cameras from the 1960s would have been ill-equipped to photograph in the extreme conditions of space with temperatures reaching 120°C in the sun and plummeting to negative 65°C in the shaded vacuum of outer space. NASA worked closely with the Swedish manufacturer Hasselblad to develop the lightest possible camera to accompany the astronauts into space. With no room for error or time to reshoot images, the Hasselblad Data Camera, fitted with a Zeiss lens specifically designed for NASA, traveled to the moon on Neil Armstrong’s chest to capture some of the most well-known images of the Apollo missions. For the journey home, the film was removed from the camera, while its body was left behind to meet the strict weight requirements for travel back to Earth. In total, 12 abandoned camera bodies accumulated on the lunar surface after missions Apollo 11 to Apollo 17.

The images are much more than their impressive technical feats, though. Their carefully crafted compositions and technical skill cement their status as true works of art. The market for vintage NASA photography differs from the traditional fine art photography market due to the finite number of printed photographs. These works were not made to be sold to collectors or galleries: They weren’t always printed in standard sizes, nor were they editioned. Rather, the photographs were printed for specific purposes as individual works, meaning variations in print date led to variations in color.

Most were printed on eight-by-10-inch fiber paper bearing the “A Kodak Paper” watermark on the reverse. In 1972, around the same time as the final Apollo 17 mission, Kodak altered its watermarks to read “This Paper Manufactured by Kodak.” In the margins of vintage NASA photographs, red NASA numbers correspond to the image and are coded to indicate the mission.

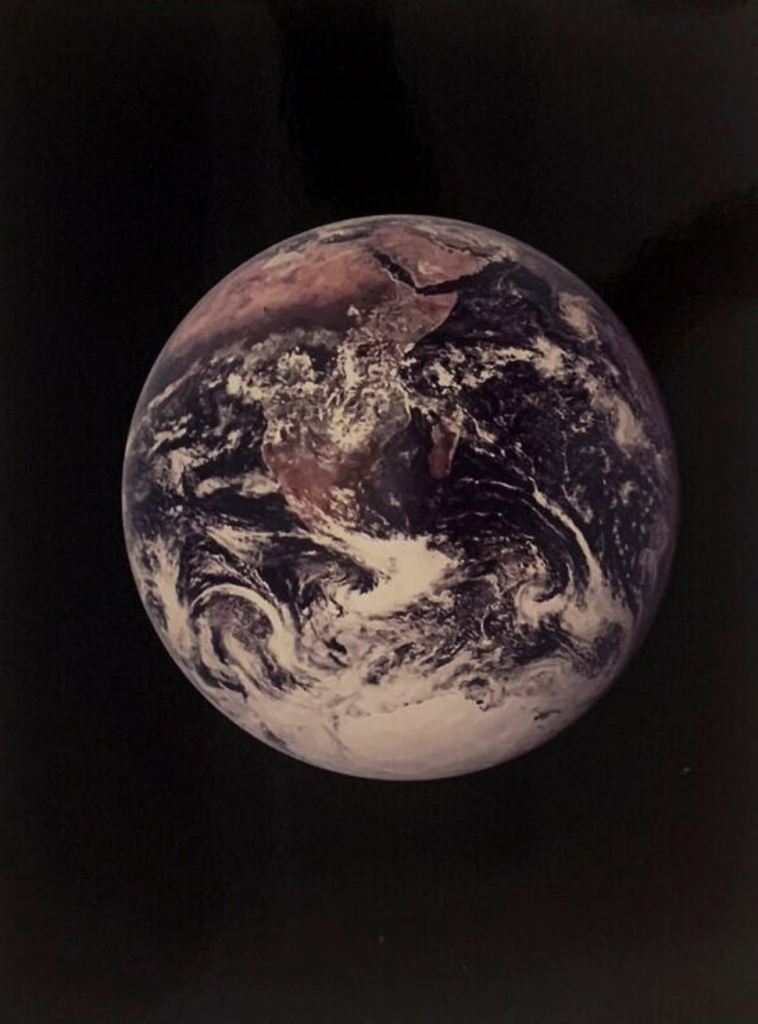

In this auction, some of the lots also have purple NASA stamps on the reverse of the image with a description of the scene and NASA identification numbers. Larger versions of images were typically used for scientific presentations or political gifts and are much rarer to come to market. Artnet Auctions’s sale “The Final Frontier: NASA Photographs from the 1960s” includes several notable examples of this presentation size image, including the Blue Marble, as viewed from the Apollo 17 mission, and James Irwin saluting the American flag, taken by Apollo 15 Commander David R. Scott.

NASA’s images of the Earth seen from the moon dramatically altered the way society viewed our planet and our relationship with the environment. When viewed from a distance, such as in the iconic Earthrise image from the Apollo 8 mission, our small blue planet appears beautiful in solitude. The desolation of the lunar surface in the foreground contrasts with the vibrancy of the Earth’s oceans and the energy of its swirling clouds, starkly represented against the unending blackness of space.

Recognizing the importance of this type of imagery, NASA released this Earthrise photograph after cropping the image and rotating it 90 degrees, making the Earth appear larger at a more recognizable angle.

Images like the Blue Marble from the Apollo 17 mission and the Earthrise shot, taken by Astronaut Bill Anders during the Apollo 8 mission, spurred environmentalist feelings across the globe as the fragility of our planet was affirmed through photography.

“To me it was strange that we had worked and had come all the way to the moon to study the moon,” Anders said during the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 8 mission, “and what we really discovered was the Earth.”

At the time of the Apollo missions in the 1960s and 1970s, as the U.S. was shaken by assassinations, civil rights protests, and the Vietnam War, the successes of these trips fulfilled the long-held hopes that man could reach the stars, uniting the nation toward a common goal. Looking at today’s America and its deep divisions, our circumstances are not so different—our quest for understanding the world beyond our planet continues.

With this cultural backdrop and the renewed media spectacle surrounding space tourism by billionaire thrill seekers, the images presented in “The Final Frontier: NASA Photographs from the 1960s” are particularly relevant to today’s collectors.