When Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson died of heart disease in 2015, she bequeathed the entirety of her estate to her hometown museum, the Columbus Museum of Art.

Now, after five years of tirelessly sorting through the artist’s artworks, journals, and various personal possessions, curators Carole Genshaft and Deidre Hamlar are presenting the first posthumous exhibition dedicated to Robinson’s seven-decade career.

“I think she knew what she was doing and the enormity of this task,” Genshaft told Artnet News. “I like to describe it as, if you’ve had a parent or a grandparent who passed away and you went through their house and they lived in the same place for 40 years. That’s a daunting task, but multiply that by about 10 or 20 or 100.”

The resulting show, “Raggin’ On: The Art of Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson’s House and Journals,” isn’t confined to artworks. There are the homemade furnishings Robinson used to decorated her home; selections from her collections of thimbles, dolls, and buttons; and selections from her expansive library, which filled 75 boxes on its own, and her 150 journals, which include reflections on attending the 1963 March on Washington.

“Aminah was as much a literary artist as she was a visual artist, and those writings could have been done this summer, after the George Floyd protests. There is very similar language about how now it’s finally time for things to really change,” Genshaft said.

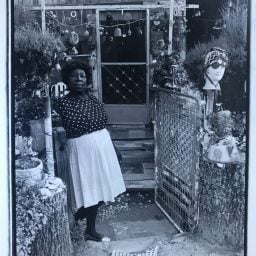

Aminah Robinson’s home was filled with artworks, books, and personal effects before it was turned into an artist residency by the Columbus Art Museum. Photo courtesy of the Columbus Museum of Art.

An advocate for social justice as well as women’s and African American history, Robinson was awarded a MacArthur genius grant in 2004. The foundation recognized her as a folk artist who excelled in “celebrating themes of family, ancestry, and the grandeur of simple objects in drawings, paintings, and large-scale, mixed-media assemblages.”

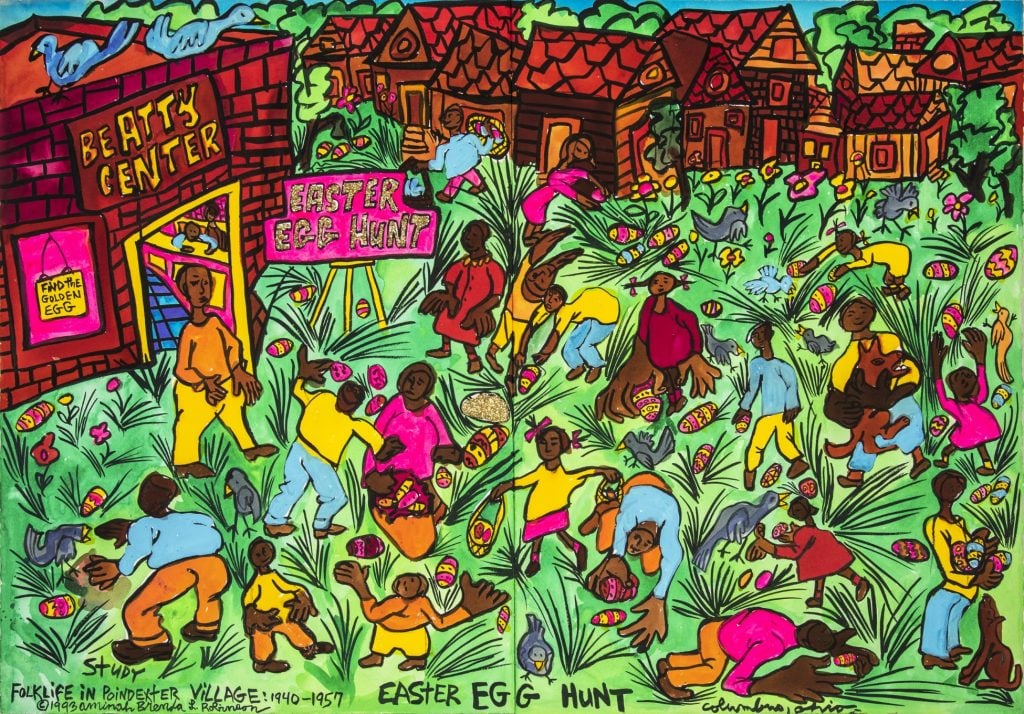

For Robinson, the boundaries between art practice and everyday life were porous: each moment was another opportunity to record African American culture and transform lived experiences into works of art. She called her art “the missing pages of American history.”

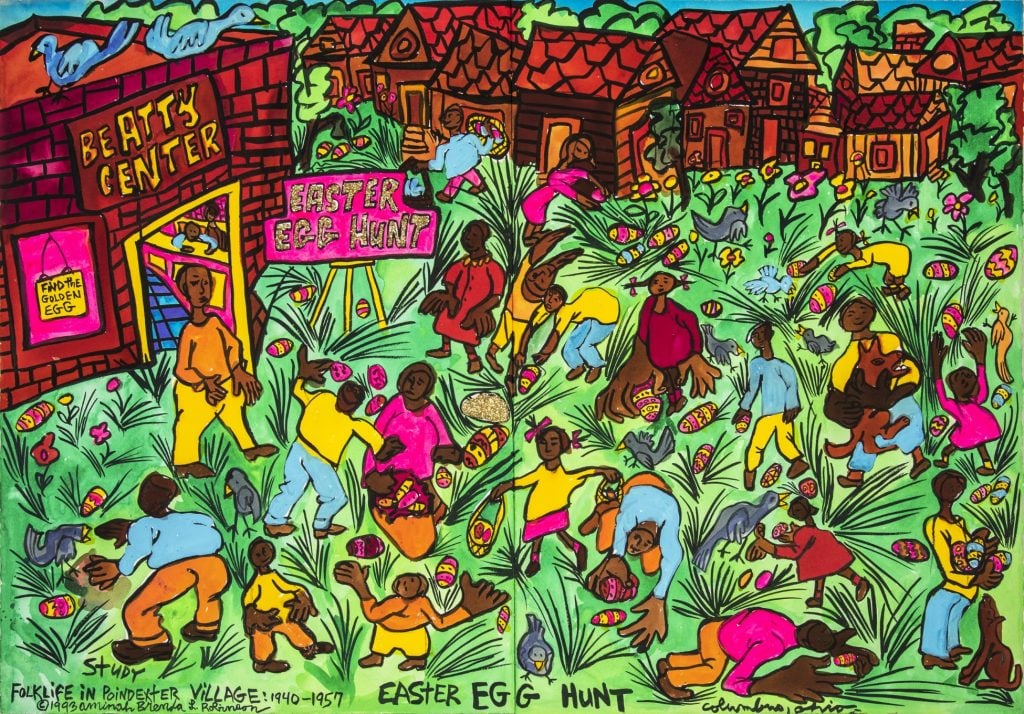

Much of Robinson’s work is specifically about Columbus—particularly Poindexter Village, the African American community where she grew up, and one of the nation’s first public housing projects. But it also “speaks universally to what happened to African American communities all over the country,” said Genshaft.

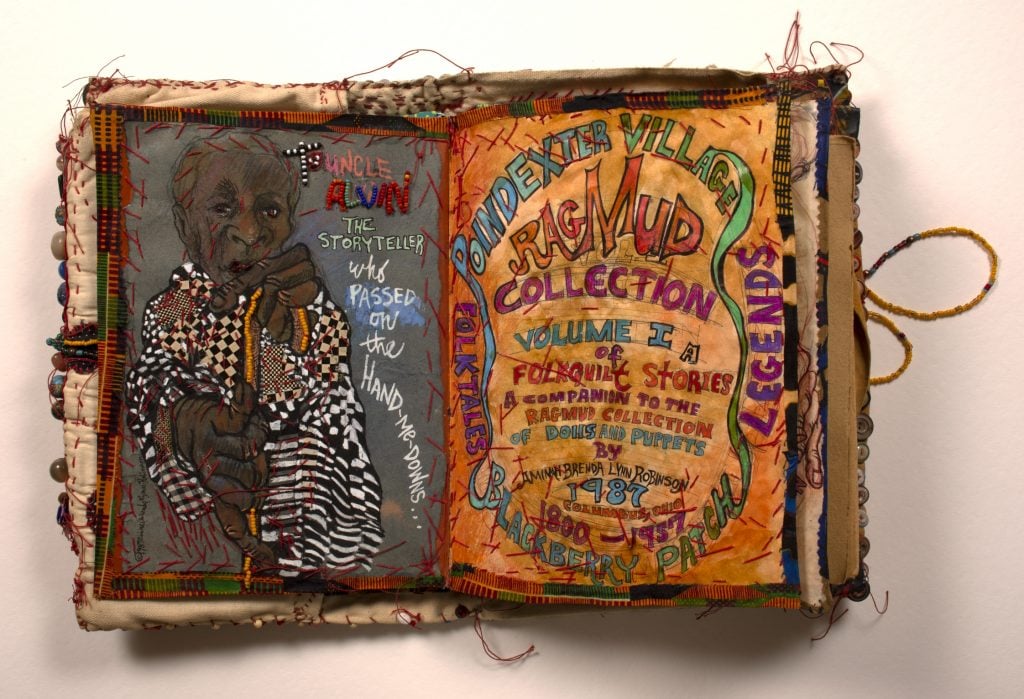

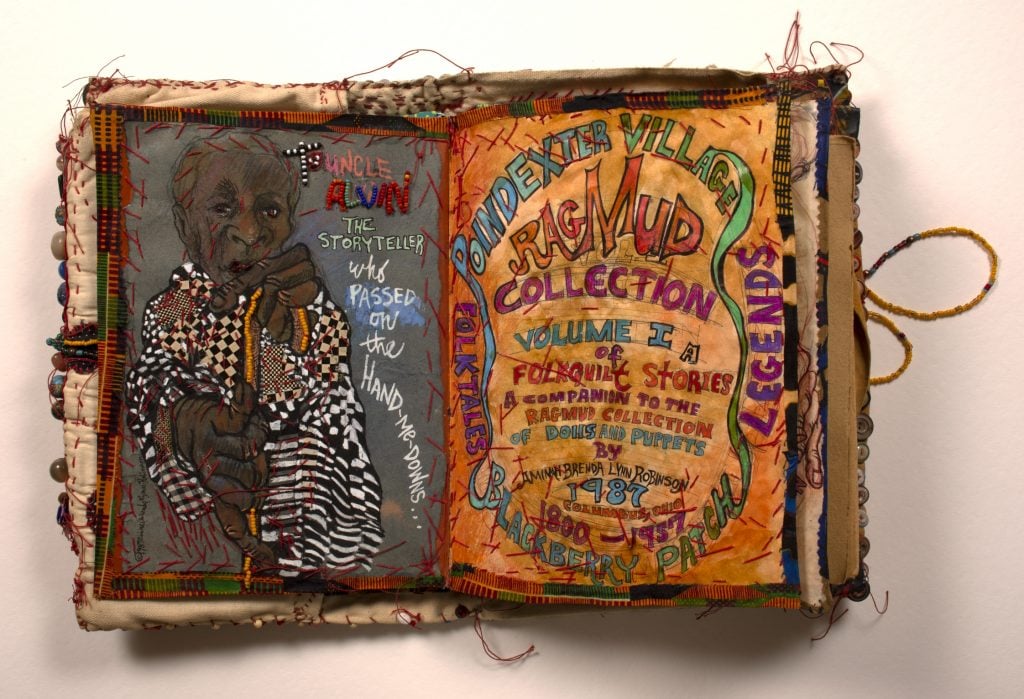

Drawing was the artist’s first form of communication, until she learned to talk at around age five. Before that, Robinson would sketch in notebooks that her father made from hogmawg, a homemade paper mixed from mud, glue, twigs, leaves, animal grease, and lime that remained a staple of her work throughout her life.

Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, Poindexter Village Ragmud Collection (1987). Photo courtesy of Columbus Museum of Art, estate of the artist.

Robinson began attending Columbus Art School (then part of the museum, now the Columbus College of Art and Design) when she was still in high school, before studying art history and philosophy at Ohio State University. Her drive to understand her roots led her to travel through Africa beginning in 1979. It was there that Robinson took her first name, adding it to her birth name, Brenda Lynn, during a religious ceremony.

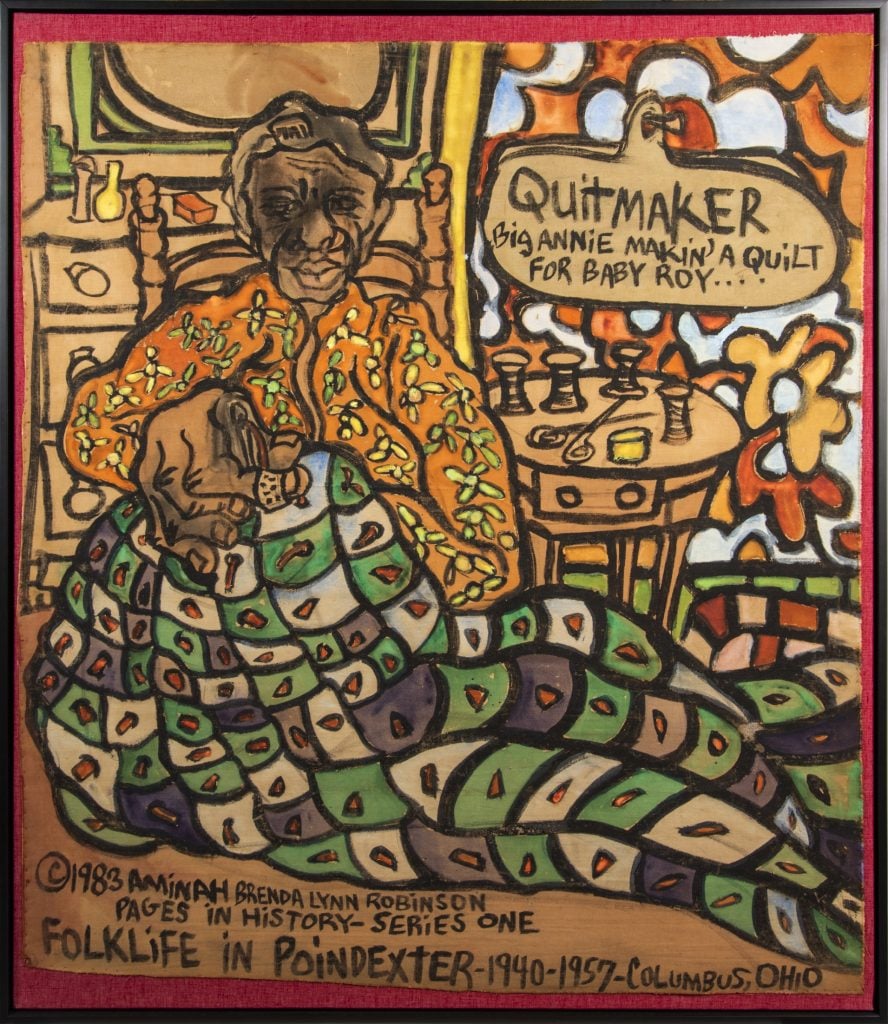

In her work, Robinson wasn’t restricted to traditional fine-art materials: the artist regularly incorporated found objects, twigs, shells, scraps of cloth, and other non-conventional materials into her painting and sculptures.

Her inspiration was the African concept of Sankofa, which stresses the importance of understanding the past to make progress.

“It’s about the necessity of knowing where you come from and understanding that before you act in the present or go on into the future,” Genshaft explained. “That guided her whole process.”

Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, Easter Egg Hunt (1993). Photo courtesy of the Columbus Museum of Art, estate of the artist.

It also meant that art-making was a never-ending activity, and the artist continually revisited and reworked old works. Robinson dubbed her series of quilted mixed-media works, which she was constantly adding to, “RagGonNons.”

“The idea is that it rags on and on,” Genshaft said. “Aminah worked on these for years, sometimes decades, and she would have them all rolled up on a table in her living room. Once in a while she would roll it out on her driveway.”

The biggest one curators found at her home, Themba, measures 118 feet long and weighs 200 pounds. The tapestry, densely encrusted with buttons, beads, and other objects, was inspired by Robinson’s father’s aunt, Cornelia Johnson, who told her young niece stories about how their ancestors had survived slavery in Georgia.

“The driving force behind creating this work was to create a record for what had been lost through the oppression of slavery,” Genshaft explained. “Amina really felt compelled to tell the story of Africa before slavery, of the kidnapping of Africans, the Middle Passage, forcing them into bondage, and the whole gamut of African-American history, the emancipation, the migration North.”

Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, Dad’s Journey (1972–2006). Photo courtesy of the Columbus Museum of Art, estate of the artist.

In the piece, the titular figure represents a kind of mythic person, at once Robinson’s aunt and an African everywoman. The unfinished work is so massive curators weren’t able to include it in the exhibition, but a smaller, 20-foot long “RagGonNon,” Dad’s Journey, is among the works on view.

The exhibition also showcases Robinson’s home as a work of art in its own right, with carved murals on the front doors (now replaced with weather-safe vinyl copies), handmade tile mosaic floors, and a bottle tree garden—a Southern folk art tradition that originated in the Congo—in the front yard.

The Aminah Robinson Artist Residency. Photo by Ira Graham, courtesy of the Columbus Museum of Art.

It was a natural fit when, in honor of what would have been Robinson’s 80th birthday this past February, the museum announced plans to convert it to a residency for Black artists.

The ribbon cutting for the Aminah Robinson Residency took place in July, after a renovation project supported by a $200,000 Columbus Foundation grant. (The first resident, Johnathan Payne, will move in next summer.)

It’s all part of a bigger initiative called the Aminah Robinson Legacy project, which Genshaft hopes will help raise the artist’s profile outside the central Ohio region, where she is well-known.

“We’re trying to get her name out there—I know that’s what Aminah would want. She really believed this work could talk to a lot of people,” Genshaft said. “”It is such important work. Aminah really was ahead of her time.”

See more works from the show below.

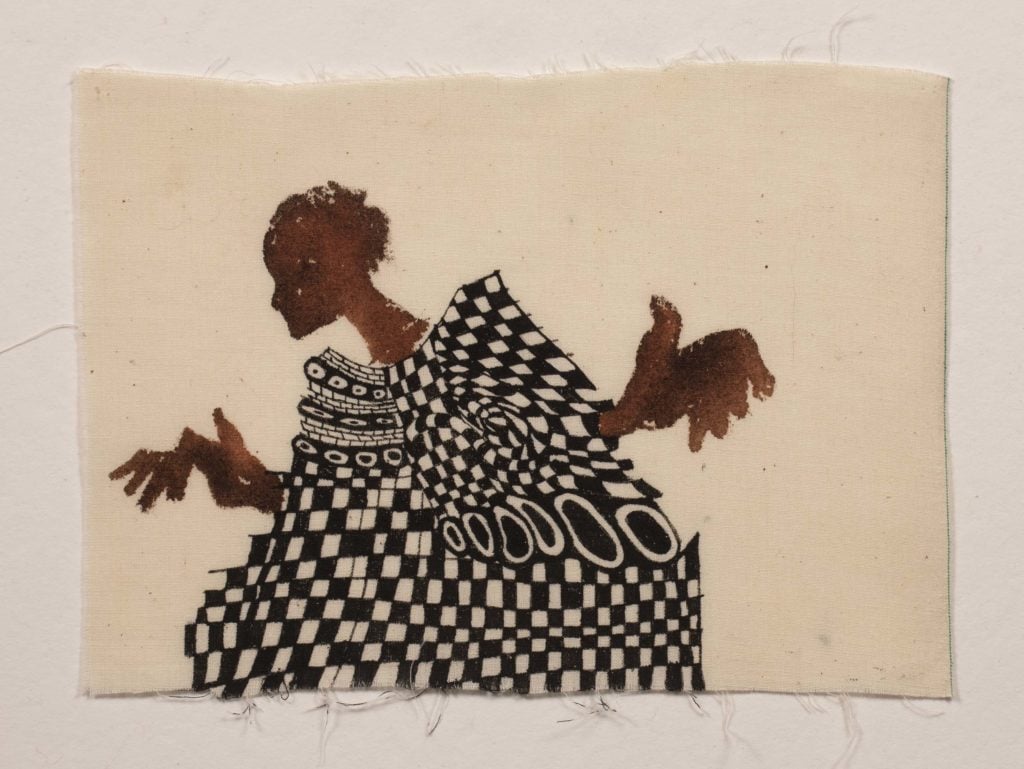

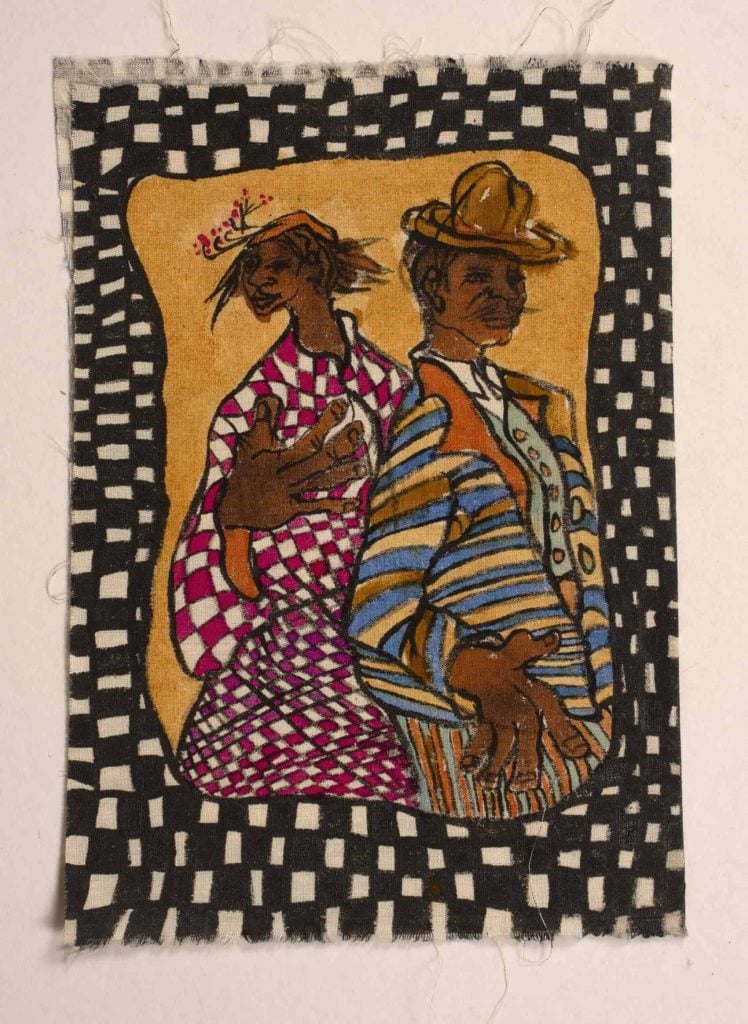

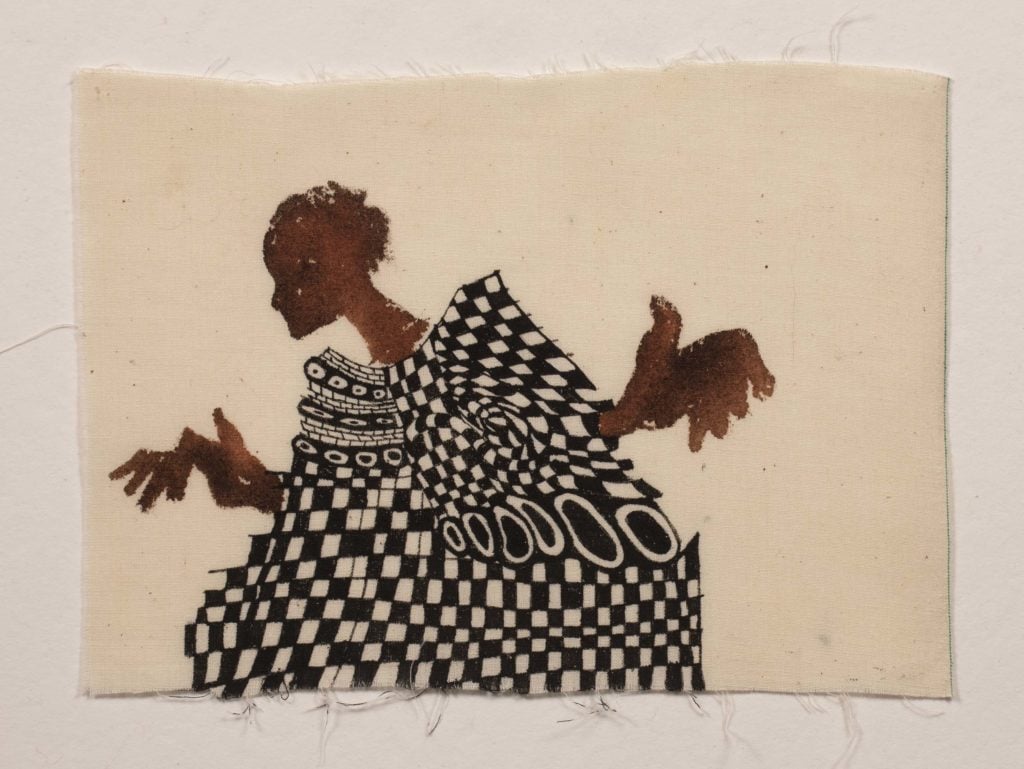

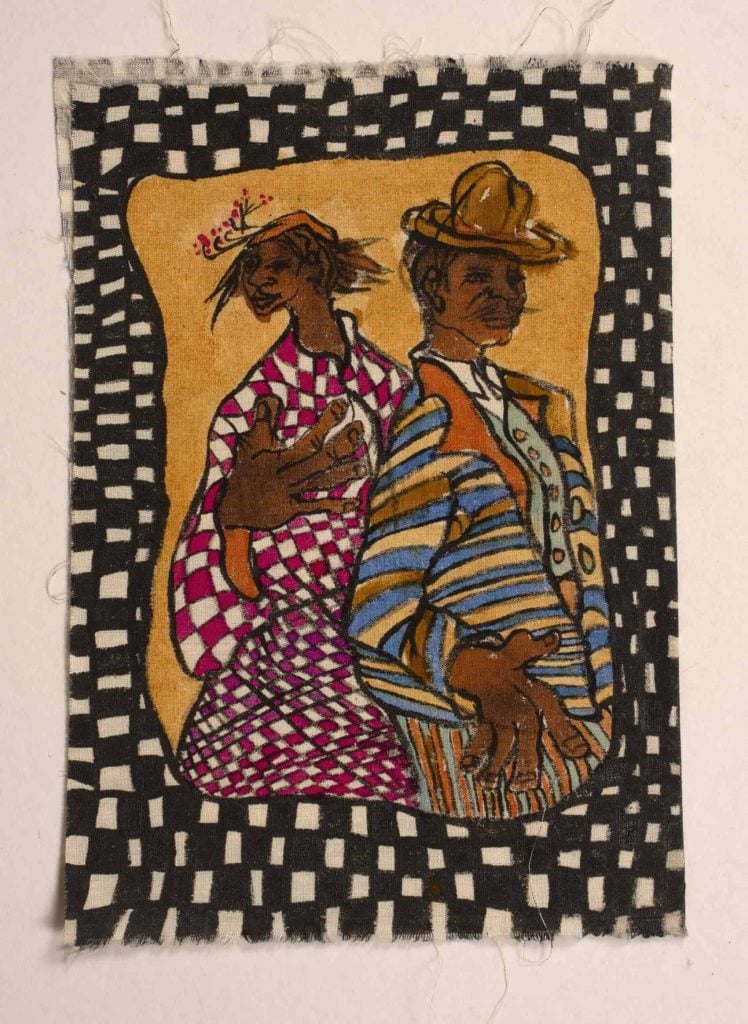

Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, from the series “Folk Costumes From the Blackberry Patch.” Photo courtesy of the Columbus Museum of Art.

Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, Untitled (table), Sapelo (box), Sacred Pages (box), 1998–2002. Photo courtesy of Columbus Museum of Art, estate of the artist.

Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, Untitled (migration), undated. Photo courtesy of Columbus Museum of Art, estate of the artist.

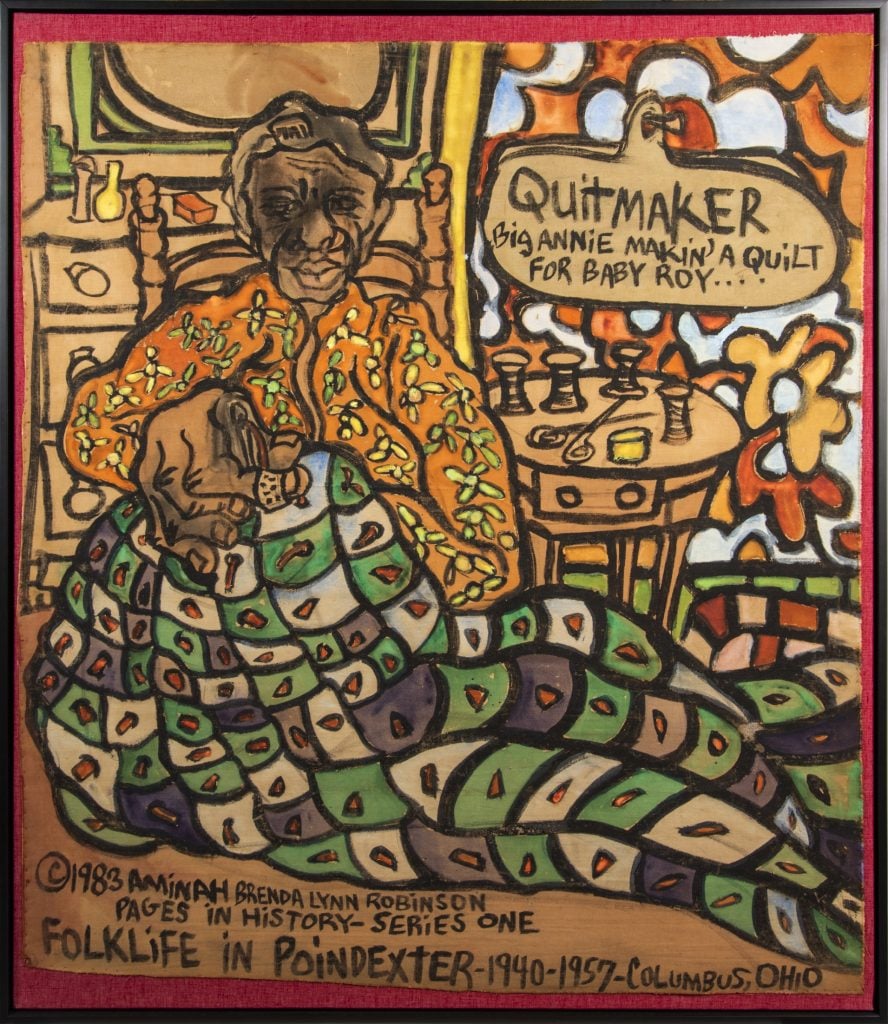

Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, Big Annie Makin’ a Quilt for Baby Roy (1983). Photo courtesy of Columbus Museum of Art, estate of the artist.

Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, Incantations (2003–07). Photo courtesy of Columbus Museum of Art, estate of the artist.

Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, Studies into the Folk Costume of the Blackberry Patch/Poindexter Village, early 1800–1957 (1980–86). Photo courtesy of the Columbus Museum of Art, estate of the artist.

“Raggin’ On: The Art of Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson’s House and Journals” is on view at the Columbus Museum of Art, 480 East Broad Street, Columbus, Ohio, November 21, 2020–October 3, 2021.