Art & Exhibitions

Andrea Fraser Brings the Sounds of Sing Sing to the Whitney Museum

She breaths new life into an old provocation.

Photograph by Nic Lehoux 2015.

She breaths new life into an old provocation.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

Whitney Museum “Open Plan.”

“More African American adults are under correctional control today—in prison or jail, on probation or parole—than were enslaved in 1850, a decade before the Civil War began,” according to Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, a fact that has led to a forty-six year spike in prison construction. Ask artist Andrea Fraser to account for this disturbing social phenomenon and she’ll link it to another unprecedented building boom: the recent explosion of museums in the US.

A pioneer of institutional critique, Fraser has breathed new life into an old provocation—thanks largely to her trenchant performances, videos, and writing. In 2005, aware that institutional critique had itself become institutionalized, Fraser boiled the trope down to a disparaging neologism: “ICK.” In 2011, she published a widely disseminated essay, “L’1% C’est Moi,” that impugned contemporary art’s complicity in the world’s unequal distribution of wealth. In 2014, Fraser took on big city racial politics with Not Just A few of Us, a mesmerizing performance that kicked off New Orleans’s Prospect 2.0.

Now, the artist has turned her attention to aurally capturing the interrelatedness of American poverty and privilege through a cavernous sound installation—it’s titled “Down the River”—inside the city’s newest architectural showpiece, the Renzo Piano-designed Whitney Museum of American Art.

As she told one interviewer recently “I am bringing the sounds of Sing Sing to the Whitney’s fifth floor to link art museums and prisons; they are two sides of the same coin of inequality.”

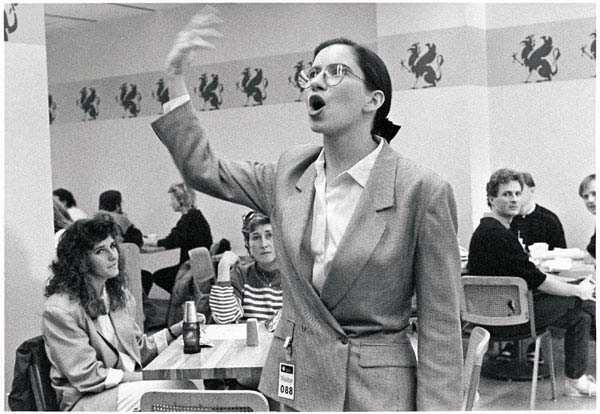

Andrea Fraser, “Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk” (1989).

Image: Courtesy UCLA.

The first of five experimental exhibitions the Whitney has baptized as “Open Plan,” Fraser’s site-specific project uses audio she recorded at the legendary Sing Sing Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison that storehouses inmates in six-by-nine foot cells and which is surrounded by guard towers, high walls and razor wire. Reproduced inside the museum’s 18,200 square foot fifth floor space—the aerie is reportedly the largest column-free gallery in New York—Fraser’s bare bones installation covers miles of geographical and moral ground. Like Alexander’s barnburner of a book, the artist’s relocated recordings bridge a massive social divide.

Located thirty-two miles north of the Whitney, Sing Sing is typical of similar correctional institutions that contain populations that have crossed America’s criminal justice system (the US leads the world in total number of people incarcerated by a wide margin) but have also been economically excluded from the nation’s labor market. The Whitney, in its turn, is emblematic of the function that today’s art museums retain as vast warehouses of wealth that serve mostly an upper middle-class museum-going public (the Whitney’s $22 general admission buys two adult movie tickets in NYC), while immortalizing the status, taste and tax advantages of the global 1%.

Polarized economies, like coins, also have two faces.

Visually, there is nothing to see in “Down the River” because the artist has chosen to leave the Whitney’s fifth floor empty. Rather than draw attention to physical objects or her excellent videos—two of these, Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk and Welcome to the Wadsworth: a Museum Tour are being screened in a side gallery—Fraser’s straightforward presentation lets the viewer concentrate on the ambient reality of life in the pen. Among the sounds piped into the vast space from discreetly installed overhead speakers are footsteps, the voices of inmates, cell doors sliding open and closed, and instructions being called out over an intercom. All these noises constitute the acoustics of confinement—at least as they are experienced inside a $422 million mega-museum.

The Whitney Museum’s new Renzo Piano-designed downtown location, opening May 1, 2015.

Photo: Timothy Schenck courtesy the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Equally jarring when considering the sounds of Sing Sing are the museum’s floor-to-ceiling windows. If the XL-sized portholes on the museum’s eastern wing look out over the expensive new condominiums and developments that followed the arrival of the High Line, those on its western flank soar over the concrete and asphalt of New Jersey, as well as a large swath of the brimming Hudson River below. Birds hover and swoop over the water with the Statue of Liberty as a backdrop. If you follow the same riverbank upstream, you will eventually arrive at the gates of Sing Sing.

According to the wall text Fraser authored, the US has experienced a joint boom in museum and prison expansion since the 1970s that has tripled the numbers of both kinds of institutions. In the artist’s view, bringing together these parallel trends into a single artwork materializes some of their massive contradictions. In practice, her installation also makes for a humongous, largely wordless noise poem that occupies the space where our understanding of these inarticulate social forces should be. Kudos to the artist and the museum for giving them a voice.