On View

Zoë Buckman Sends Post-Harvey Hollywood a Message With Her Public Sculpture of a Boxing Uterus

This uterus packs a punch.

This uterus packs a punch.

Sarah Cascone

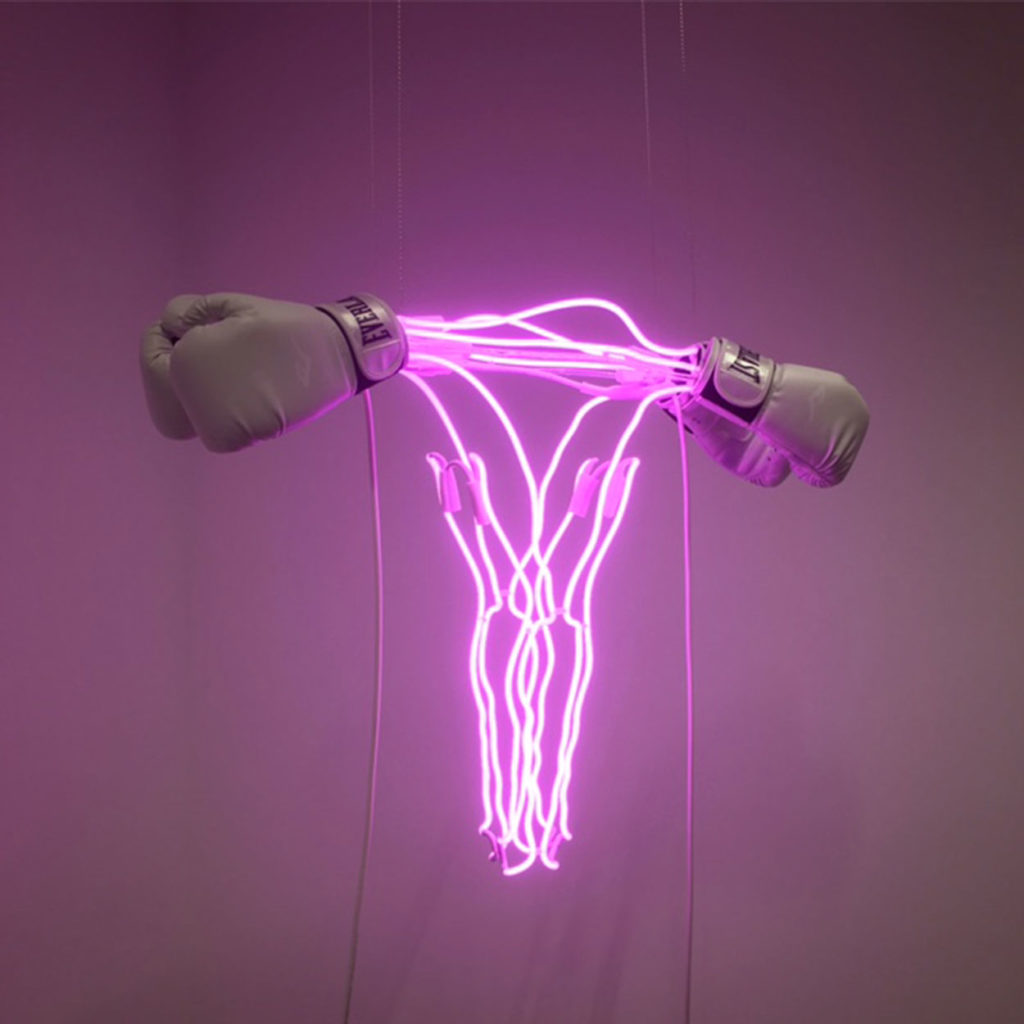

An in-your-face reminder of the women’s movement and its newfound ability to topple men in positions of power has risen in Los Angeles. Zoë Buckman’s Champ, a glowing neon pair of ovaries clad in boxing gloves, stands 43 feet tall outside of the Standard, Hollywood, overlooking Sunset Boulevard.

Organized by Art Production Fund, the British artist’s first public sculpture will debut today, just ahead of the Academy Awards, and will remain on view for a year.

Although Champ has been in the works for nearly two years, it feels custom-made for the current moment. “The pay gap is very obvious and apparent in Hollywood, and it’s no secret that there’s been systemic sexual harassment and assault in the industry, so we knew all that going in,” Buckman told artnet News ahead of the project’s unveiling. “I just didn’t know that the rest of the country would be thinking those things as well.”

Bethanie Brady, who runs an artist management firm, first put Art Production Fund and Buckman in touch back in 2016, after a smaller version of Champ appeared at New York’s Jack Shainman Gallery. It was part of “For Freedoms,” a group exhibition curated by Hank Willis Thomas and Eric Gottesman’s artist-run superpac. (That December, Champ became something of an Instagram sensation at PULSE Miami Beach, and it is now on view through September in “The Future Is Female” at Cincinnati’s 21c.)

“Over the past few years, as we have worked through production and fundraising for the project, this incredible work has become relevant for even more reasons,” said Casey Fremont, Art Production Fund’s executive director, in an email. “It’s an undeniably powerful and empowering symbol that can’t be ignored.”

Zoë Buckman, Champ. Photo courtesy of the artist.

“Everything I’ve made has always been speaking to the female experience, whether that’s personal or political,” said Buckman. “It’s really encouraging and rewarding to see these ideas so widely discussed.”

Buckman first began working in neon following the birth of her daughter in 2011. Her “Present Life” series was inspired by her own placenta, which she had plastinated and turned into a sculpture, and included a series of placenta-themed works, with some in neon. A graduate of New York’s International Center of Photography, Buckman saw the medium as a natural extension of her work with the camera. “In photo school, they teach you that light is your paintbrush,” she said. “In that body of work, I wanted to create a neon placenta. I don’t think I realized until just now that that was a building block to Champ.”

Champ is Buckman’s largest sculpture to date, but the biggest challenge was fundraising, which included an ongoing sale of $1,500 embroidered works. “It’s incredibly difficult to get political, feminist-driven art supported,” said Buckman. “Lots of people want to create the illusion that they are supporting feminist messaging, but when it comes to spending money, most brands and companies were afraid of the criticism they could face by putting their names to this piece.”

Zoë Buckman with work from her “Let It Rave” series. Photo courtesy of Art Production Fund/BFA.

While she’s out on the West Coast, Buckman will also celebrate the first full exhibition of her sculpture series “Let Her Rave” at Gavlak Gallery. Featuring boxing gloves—Buckman has boxed since 2015—made from scraps of lacy, bedazzled wedding dresses, the works are inspired in part by a stanza from “Ode on Melancholy” by poet John Keats: “Or if thy mistress some rich anger shows / Imprison her soft hand, and let her rave.”

“It’s my favorite poem, but I’ve always had a problem with that line and its implied imprisonment of a woman and allowing her to rave, giving her permission to do something that’s instinctual and natural to the human experience,” said Buckman, who estimates that she used about 30 wedding dresses in the work.

The intricately sewn sculptures—delicate, feminine details surrounding the masculine form of the boxing glove—speaks to this idea of being hemmed in or held back. “It does give this impression of a cloying sense of perfection, purity, and chastity,” Buckman said. “It’s looking at marriage as a social contract to keep women adhering to certain patriarchal ideas.”

Zoë Buckman, Champ (2018). Photo by Veli-Matti Hoikka, courtesy of Art Production Fund.

Champ, on the other hand, eschews frilly embellishment. The unadorned boxing gloves suggest a woman who’s unafraid to fight back and embrace power. Unlike the smaller piece of the same name, which glowed a bright pink, the new sculpture is all white, with additional neon tracing of the outside of the boxing gloves to make the work more visible at night.

“The white light has a gender-neutral quality,” Buckman said. “I do hope it will draw men into these conversations”

An undeniable celebration of the strength and resilience of women, Champ is also confrontational. “I want it to disrupt the space and the moment we’re in,” Buckman said, “and remind us of the stakes—what we have to fight for and what’s under threat: women’s access to sexual health, and their right of choice.”

“Zoë Buckman: Champ” will be presented by Art Production Fund with support from alice + olivia by Stacey Bendet at the Standard, Hollywood, 8300 Sunset Blvd, West Hollywood, February 27, 2018–February 27, 2019.

“Zoë Buckman: Let Her Rave” is on view at Gavlak Gallery, 1034 N. Highland Avenue, Los Angeles, March 3–April 7, 2018.