Reviews

Paris Show Charts the Rise and Fall of Photography’s Love Affair With Cars

At Fondation Cartier, a survey of cars as a photographic subject matter honors a genre in decline.

At Fondation Cartier, a survey of cars as a photographic subject matter honors a genre in decline.

Sarah Hyde

Last week, on a rainy morning in Boulevard Raspail, the bleary-eyed intellectuals of Paris’s photography elite gathered at the Fondation Cartier to consider, and scrutinize, the latest long-anticipated offering, “Autophoto.” The exhibition is a selection of 500 images of cars, curated by Xavier Barral and Phillipe Seclier, and conceived as a response to the exhibition “Hommage a Ferrari” that the Fondation Cartier hosted some 30 years ago. Nowhere in the world do they take photography more seriously than in Paris’s Rive Gauche, and to this audience, the selection of each print, by artist, date, and method of production, has significant ramifications.

Works range from an Eve Arnold’s iconic 1961 images of Marilyn Monroe on the set of The Misfits, where the legendary star happens to be in a car, to the work of photographers who have made the subject matter their own, like William Eggleston, Lee Friedlander, and Robert Frank. And while the automobile motif is a cohesive force for selection, the diversity of images included is a testament to the ingenuity of photography and the various permutations that it can achieve.

Óscar Fernando Gómez, from the series Windows (2009) Courtesy Martin Parr Studio, Bristol ©Óscar Fernando Gómez

However, that also means that the curatorial direction is essentially inclusive and, thankfully, undidactic, but without an obvious powerful conceit: the entrance ticket for each image is that it must be orientated around the car but the spectator is left to draw their own conclusions. Indeed, there are many subtle threads that can be picked up on, giving plenty to satisfy the curious and knowledgeable.

One of these threads is changing the collective cultural memory of the car. While this is firmly rooted in American culture, the exhibition considers how this genre has been used and mirrored in other countries and contexts, for example, in the former Eastern Bloc, Japan, and Africa.

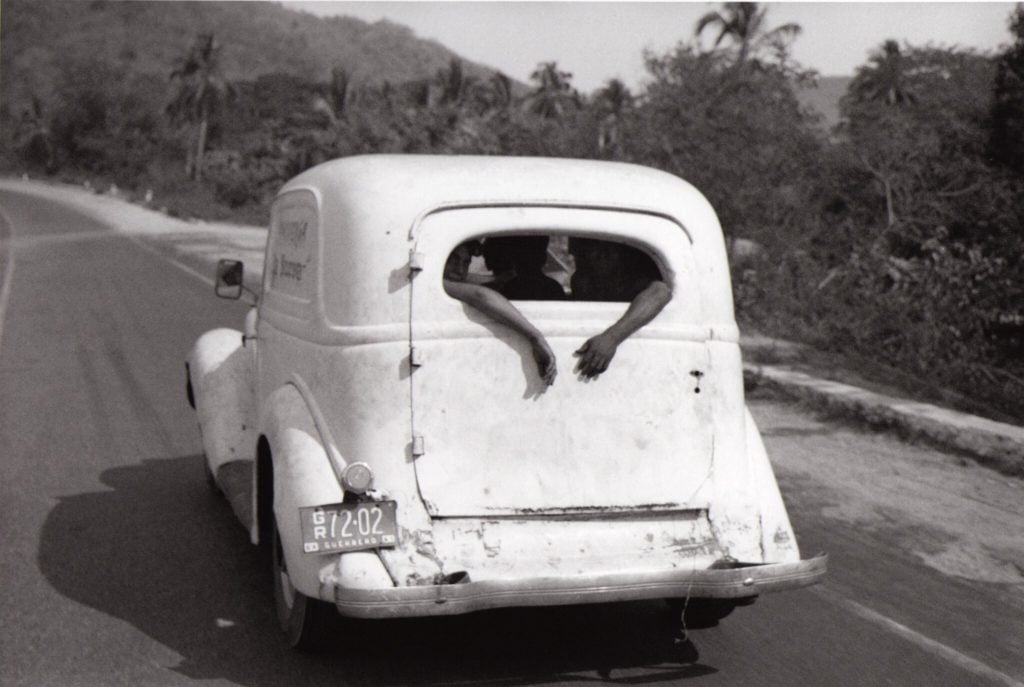

Bernard Plossu, On the Acapulco road, Mexico (1966). Courtesy Galerie Camera Obscura, Paris © Bernard Plossu

The use of photography for police evidence is established by the inclusion of two car crash images by Weegee, and then followed up by some incredible and thought-provoking images by Arwed Messmer, who captures the actual moment when East-German police arrested escapees hiding in cars on their way to the West. Both drivers and hidden passengers were photographed at the moment of their arrest; remarkably, in one of the images we see a mother and her son being forced to reenact their escape for documentation in the boot of a BMW, inside a customs house. The subjects’ eyes are blurred out. Perhaps it’s better that we cannot see their sadness and humiliation.

However, American antecedence in the genre of car photography must be acknowledged and the real majesty is found in the works of the great American photographers.

In particular, there are many works from Robert Frank’s epic two-year road trip which began in 1955. Frank was sponsored by the Guggenheim Foundation to journey across the US and photograph how Americans live, work, and spend their leisure time. He created a broad picture-record of things American past and present. These images, which coincided with the literary works of the Beat Generation, helped shape our concept of the freedom associated with being on the road, and the American road trip.

Frank took over 20,000 photos during his journey, editing them down to 83 which were finally selected by him for publication. The Americans was initially published in France in 1958, and then a year later, with an introduction by Jack Kerouac, in America. The format of his book matched that of Walker Evans’s 1938 publication American Photographs. (Coincidentally, a Walker Evans retrospective is opening in Paris at the Centre Pompidou on April 26.)

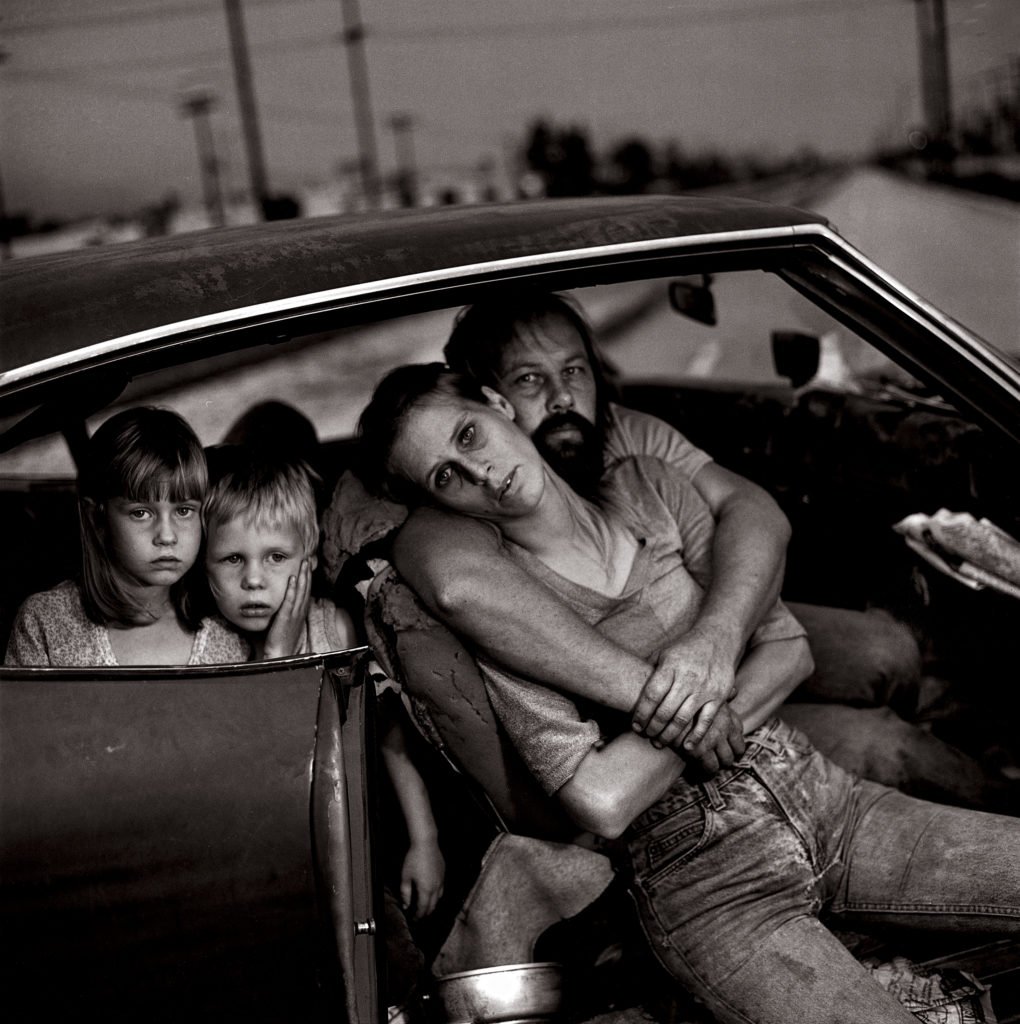

Mary Ellen Mark, The Damm Family, ( Los Angeles, 1987). ©Mary Ellen Mark, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Frank’s photographs are humbling and powerful; the images of the Ford River Rouge complex in Detroit in particular still have the power to shock. The photographer described the factory, saying “Ford is an absolutely fantastic place, every factory is really the same but this is God’s factory and if there is such a thing—I am sure that the devil gave him a helping hand to build what is called Ford’s River Rouge Plant.”

The message is clear: The shiny, utopian manifestations of the American dream—one that every household could have—were being created in human hell holes. Although as photography expert Nancy W. Barr describes in her excellent essay in the show’s catalogue, the financial stability that these factories temporarily provided was the financial engine that drove the dream that the ubiquitous cars symbolized.

Mary Ellen Mark’s iconic image of the Damm family in Los Angeles, from 1987, is remarkable, and despite the dreadful nature of their circumstance, something, perhaps love or the photographer’s incredible skill, gives this family their powerful dignity.

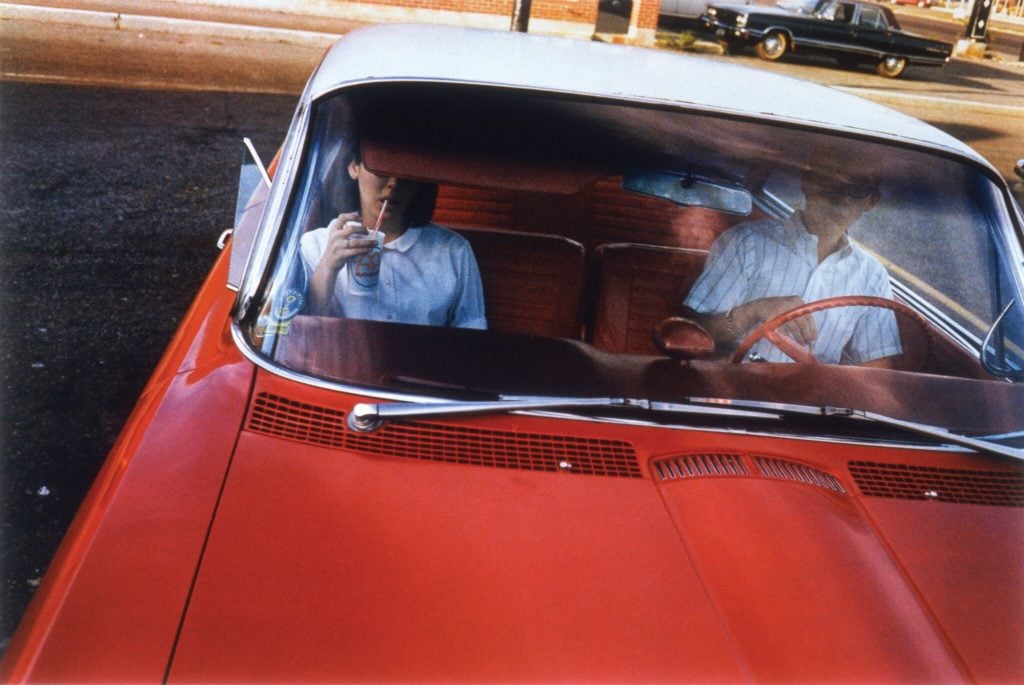

William Eggleston, Los Alamos series (1965-1968). Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London © Eggleston Artistic Trust, Memphis

Like Frank and Evans before him, Eggleston’s contribution to this genre is the stuff of visual legends. Through his brightly colored images, we gain a sense that we have actually visited these supermarkets, drive-in cinemas, and diners, and heard the courteous southern drawl of their various attendants.

The words of Allen Ginsberg’s My green automobile spring to mind in front of his image of the three brilliantly colored, long, low American green rides. The images are powerful—is it the dye transfer method that saturates them with color or the way the artist brilliantly balances the tension between the abstraction and composition? By engaging with one slightly weary but otherwise perfect housewife, and by capturing the look in her eyes, a moment is crystallized forever.

Eggleston, along with Juergen Teller, is one of the photographers who has had an enduring relation with the Foundation: his first solo show in France was held at the Fondation Cartier in 2001. The photographer’s elegant twinkly presence at the opening establishes his sovereign role in this field, although, tragically, looking at the birth dates of these great defining figures of the genre, you realize that nothing stays the same. Like the car, and perhaps the American dream itself, these great photographers which once felt so solid will soon also pass into the annals of history and become dust.

Autophoto is on view at Foundation Cartier, Paris from April 20 – September 24, 2017