On View

Artist Dawoud Bey on Seven Photographs That Shape the Way He Thinks About Race, Landscape, and His Own Work

The photographs appear alongside Bey's own in his new show at the Art Institute of Chicago.

The photographs appear alongside Bey's own in his new show at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Taylor Dafoe

Dawoud Bey’s black-and-white photographs of northern Ohio at night look like ordinary landscapes at first glance: craftsman homes surrounded by picket fences, overgrown expanses of land, waves lurching on the shores of Lake Erie. But it turns out these photos, which Bey shot in and around Cleveland in 2017, depict parts of the Underground Railroad.

“The Underground Railroad is shrouded as much in myth as it is in fact,” the now 60-year-old artist said in a statement on the work. “Using both real and imagined sites these landscape photographs seek to recreate the spatial and sensory experience of those moving furtively through the darkness.”

Instead of documenting known stops, Bey looks at the settings around them to reimagine the look and feel of the route at twilight. The tone of the photographs is subdued, more black than white—a stylistic choice that symbolizes the darkness that fugitive slaves faced on the secret route north. It puts the artist in conversation with Roy DeCarava, one of Bey’s idols, who also employed a dark aesthetic to capture “a world shaped by blackness.”

Dawoud Bey, Untitled #1 (Picket Fence and Farmhouse) (2017). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The series debuted at the city’s Front Triennial in 2018 and now 25 of the photos appear in Bey’s show “Night Coming Tenderly, Black,” on view at the Art Institute of Chicago. The exhibition is just the latest in a recent spate of achievements for the artist. In 2017, Bey was named a recipient of the MacArthur “Genius Grant” and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, is currently hosting an an exhibition of his conceptual portraits titled “The Birmingham Project”, a new series that honors the six African Americans who were murdered in the Alabama town 55 years ago. In 2020, both the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney will show a traveling retrospective of Bey’s work.

In many ways, “Night Coming Tenderly, Black” is a spiritual complement to “The Birmingham Project”: an exercise in creating alternate historical narratives that emphasize the voices of the forgotten, overlooked, or silenced.

Dawoud Bey, Untitled #25 (Lake Erie and Sky) (2017). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

True to this spirit, for the Chicago show, Bey selected more than 30 photographs from the Art Institute’s permanent collection to accompany his own. Included are works by Danny Lyon, Carrie Mae Weems, and Joel Sternfeld, as well as archival images from unknown sources. They range in style and subject matter, from middle American landscapes to portraits of working African Americans. The relationship of these photographs to Bey’s own is unresolved; whether they are complementary, opposed, or otherwise in dialogue differs from image to image, and is often wholly unclear.

To offer some insight into this mystery, we spoke with Bey about the photographs he chose to include alongside his own and what they mean to him.

Joel Sternfeld, Domestic Workers Waiting for the Bus, Atlanta, Georgia (1983). Courtesy of the artist.

“This photograph, made in an attractive suburban subdivision, brings together two things: the constructed beauty of that landscape along with the presence of three black women in that beautiful sun-dappled place. The tension between the two becomes apparent on reading the title, wherein we learn that the women are not taking a late afternoon stroll or going home to one of these houses, but are in fact domestic workers whose place in the social landscape is one of service to the people who live in those houses.”

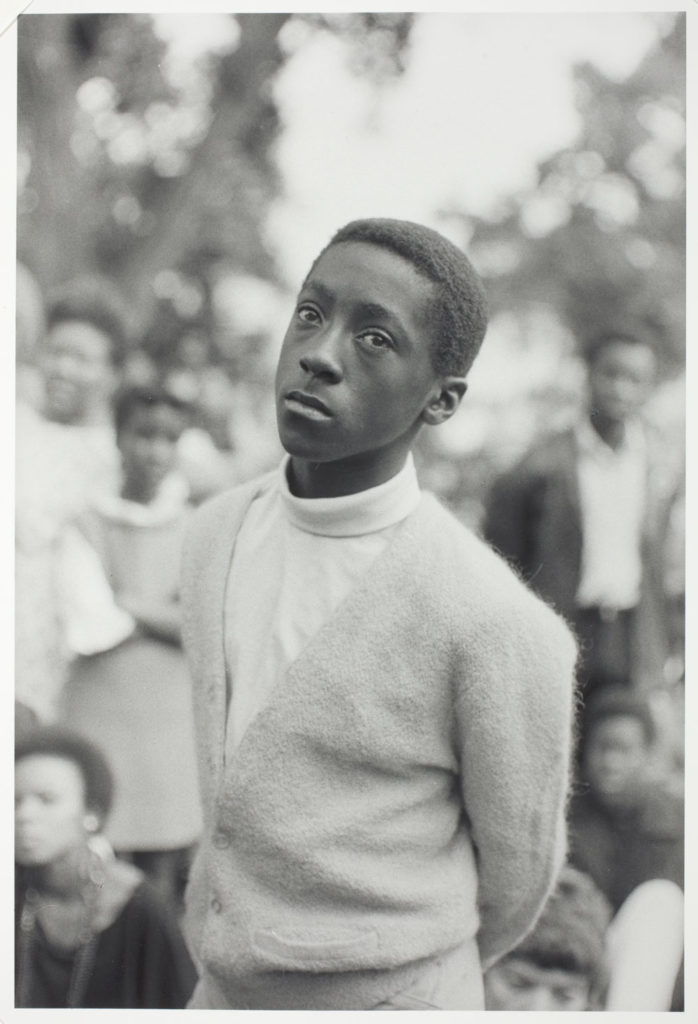

Ruth-Marion Baruch. Free Huey Rally, Bobby Hutton Memorial Park, Oakland, August 25 1968 (1996). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

“I love the relaxed disposition and gesture of the young black man in this photograph. While he seems momentarily in repose in the outdoor bucolic space of a park, he is also attending a rally to free then imprisoned Black Panther Party head Huey P. Newton. The way the relaxed black body, pastoral setting, and loaded social situation intersect make this a wonderfully complex photograph that embodies the tensions in the American physical and social landscape.”

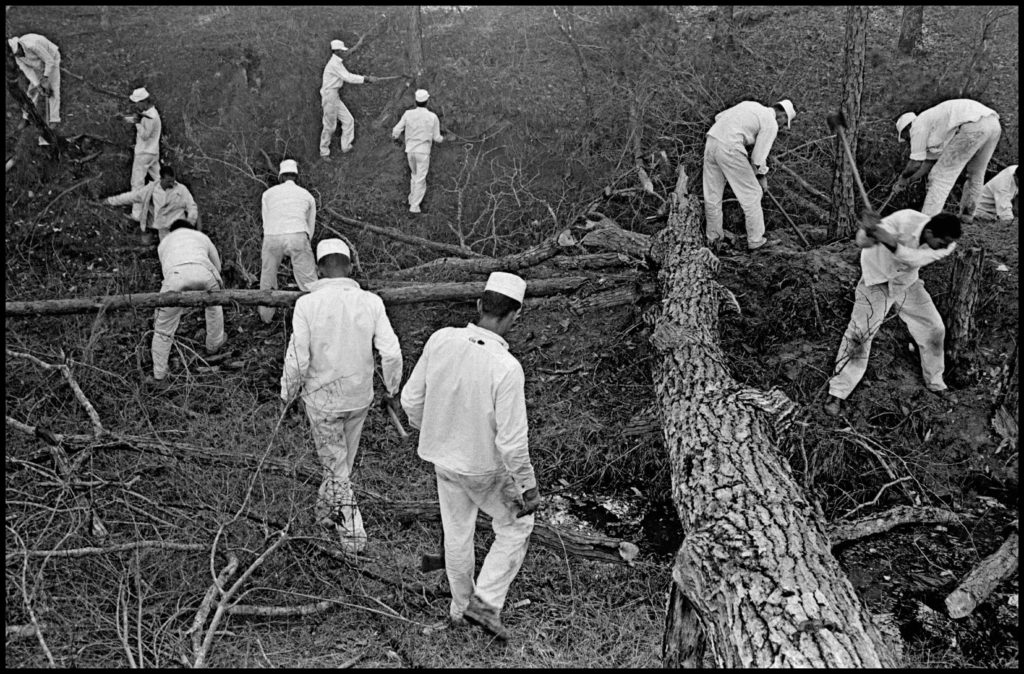

Danny Lyon. Clearing Land, Ellis Unit, 1967/69 (1979). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago and Magnum Photos.

“We often think of the wooded landscape as a place for escape and maybe reverie. The men tending those woods are not meant to experience it on those terms, but from a position of hard, imposed labor. The fact that this wooded landscape is tended by prisoners brings together two very different notions.”

Mike Smith, Carter County, Watauga, TN (2002). Courtesy of Lee Marks Fine Art, Indiana.

“This photograph to me is loaded with layers of ambiguity and tension. The eerie stillness of the scene, the greenness of the water, and what could be an item of clothing floating on the water’s surface suggests the presence of a disappeared person. It triggers the imagination for me in ways that point to the elegiac quality of the scene.”

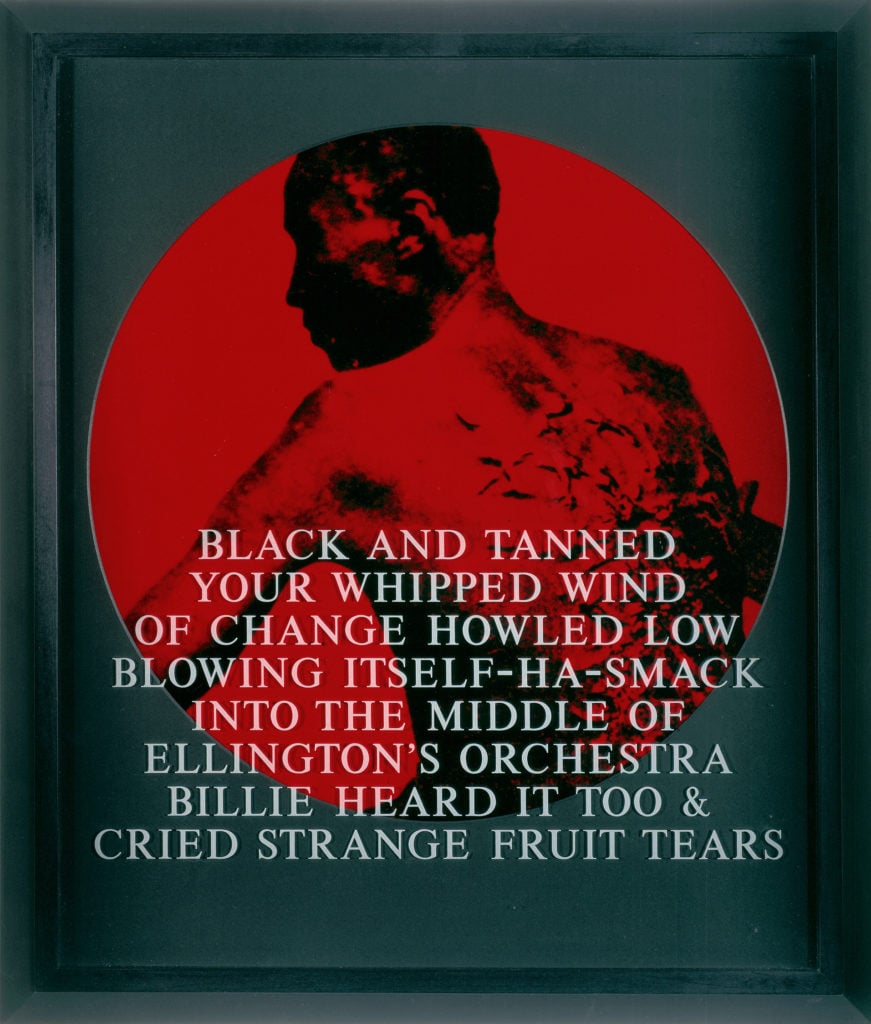

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Black and Tanned) (1995). © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

“By appropriating photographs from the African American past and inserting her own textual voice into the narrative of those pictures, Carrie Mae Weems brings an active black presence and agency to the description of an otherwise passive subject—a former slave with a horrendously whipped back—and restores to him some of his lost power, while offering a damning contemporary commentary on this sordid moment in American social history. The horror of his circumstances also suggests what made those enslaved seek their freedom via the Underground Railroad.”

Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

“Throughout our nation’s history, there has always existed an unseen parallel visual narrative, one quite different from the early narrative of docile and demeaning stereotypes of African Americans that dominated popular culture. African Americans have always pictured themselves in their own social spaces, constructing a narrative of self-authorship that confirmed their true presence in ways that were invisible to white society. These photographs populated the mantels and photo albums of black homes, private affirmations of who they knew themselves to be in the social landscape of their own lives. This photograph of a black man proudly holding a just caught fish would have been one such picture.”

John Reekie, Dutch Gap Canal, James River, Virginia (1864). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

“This 19th-century landscape photograph was one of many that began to construct a formal and photographic language for picturing the American landscape. Taking a hint from landscape paintings, photographers made pictures of a vast and seemingly unpopulated landscape that was only beginning to reveal the ways in which it would be reshaped by the human presence. There was, of course, a population of native peoples living in that landscape, but they, by and large, were not the subjects of most of the survey photographs made in the 19th century. For me, these early photographs begin to fix in the public imagination an enduring myth about the American landscape.”