Art & Exhibitions

World’s Savagery Conjured at Doris Salcedo’s Compelling MCA Chicago Retrospective

Salcedo dedicates herself to a vow of remembrance. But of what?

Photo via Bizarrebeyondbelief.com.

Salcedo dedicates herself to a vow of remembrance. But of what?

James Yood

Doris Salcedo,

Installation view, Doris Salcedo Studio, Bogotá, (2013).

Photo: Oscar Monsalve Pino.

Reproduced courtesy of the artist; Alexander and Bonin, New York; and White Cube, London.

We don’t need a monthly video from ISIS to remind us that the world can be a site of ceaseless cruelty, sadism, and savagery. These phenomena are so rooted in our species as to be instantly recognizable as part of us, even as they shame and degrade us. We measure the numbers of civilians murdered in the thousands and millions, and they become seas of individuals seemingly effaced from the human record.

As is abundantly in evidence in a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Colombian artist Doris Salcedo is one of those artists who never forgets, who in fact dedicates herself to a vow of remembrance. But of what? In an ISIS video there is a perpetrator and a victim, someone to despise and someone with whom to empathize. Political murder at a large scale, though, is usually more covert than what you can find on YouTube. It is stealthy and effaces its tracks, usually leaving little behind but the bones of the dead.

Salcedo alludes regularly to the desaparecidos, those who have disappeared; no individuals are ever depicted in her work—not the thousands of victims in Colombia or elsewhere in Latin America, or, for that matter, the militias and police forces that carried out their murders. Everyone disappears in her somewhat evanescent works, which function as political and social memento mori, not as specific records of the wrongs of a certain place and time (except for a few site-specific public projects, documented here by video).

Doris Salcedo,

Installation view, SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1998–99.Photo: Herbert Lotz

Reproduced courtesy of the artist; Alexander and Bonin, New York; and White Cube, London.

In this, her first retrospective, Salcedo reveals herself as a kind of poetically political postminimalist. Perhaps her best known series, Atrabiliarios (1992-2004), usually encases paired women’s shoes into small niche-like recesses in a wall to evoke what often remains of a desaparecida. The sepia-toned animal fiber element that provides the covering over each niche obscures the specificity of the shoes, and the stitching attaching it has a kind of raw immersion in low-tech materiality reminiscent of artists such as Lynda Benglis, Eva Hesse, and Jackie Winsor.

But Salcedo always brings everything back to remembrance. If she has a fiber piece it is shroudlike; cribs suggest coffins; furniture disassembles into dysfunction; stacks of men’s white shirts are pierced through as if by a weapon. Everything alludes to the faint presence of an absence or to the trace of disappearance. The most suggestively ambiguous body of Salcedo’s work is her interventions with old furniture—chairs, armoires, bureaus, cabinets, tables, etc.—sometimes deconstructed and reassembled, or encased in or accompanied by concrete. While still about remnants and memory, pieces such as an untitled 2007 work, in which a chair, armoire and concrete come together in a form of permanent frozen embrace, are particularly intriguing.

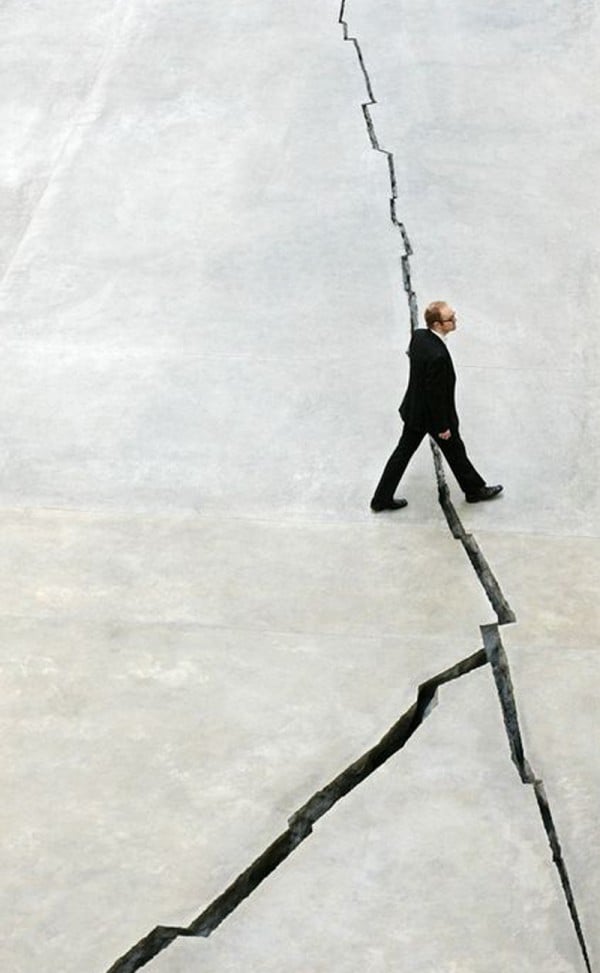

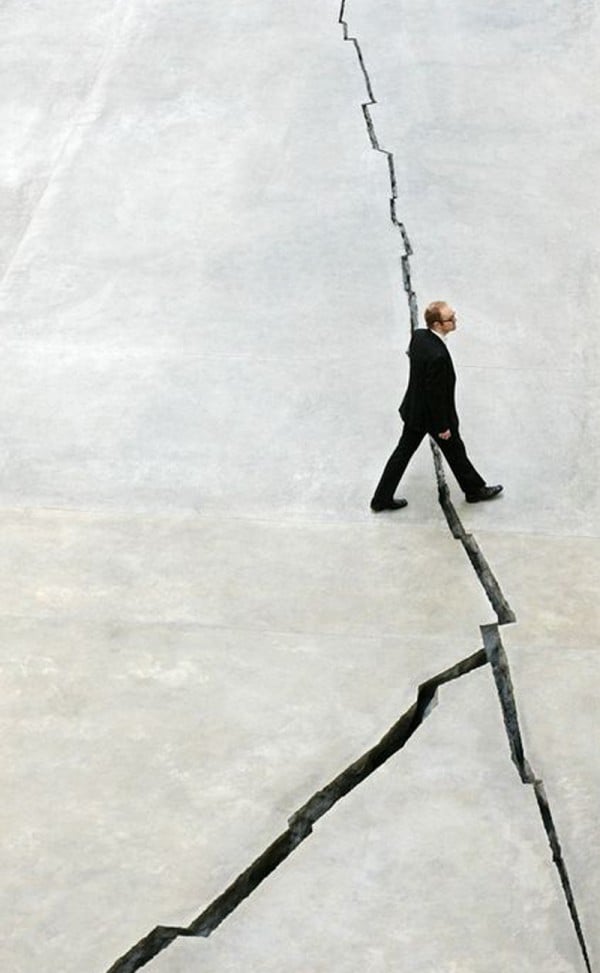

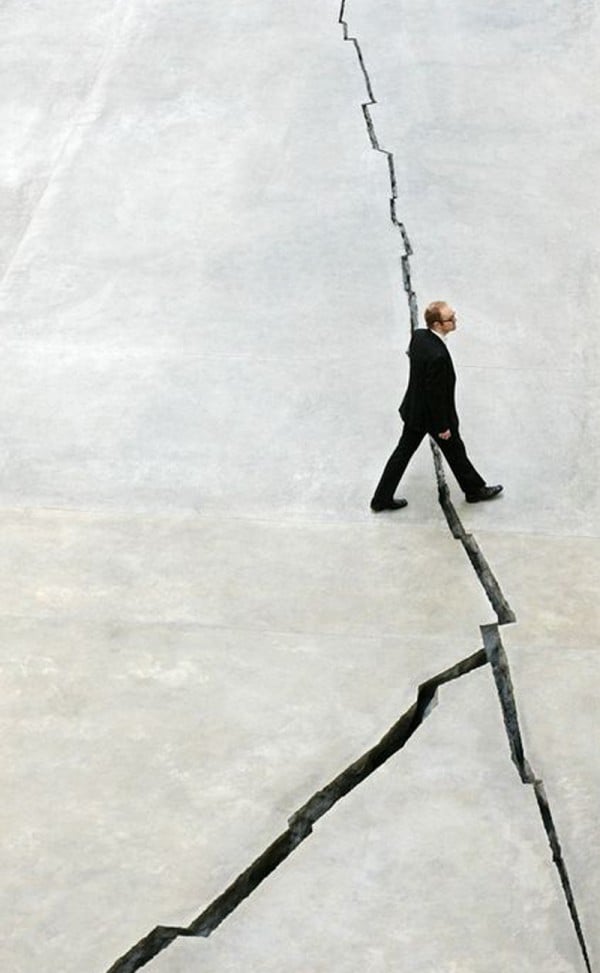

Installation view of Doris Salcedo’s Shibboleth at the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in 2007.

Photo via Bizarrebeyondbelief.com.

This is all pretty sober stuff, and there is a rarely relieved sense of dourness here. But it is an authentic dourness, and the serious and elegiac quality of Salcedo’s work was immediately and successfully communicated to the visitors around me on my visit to this exhibition, most of whom consumed the exhibition in reverent silence. They got it—while her work is rooted in the experiences of her part of the world, and while the desaparecidos she has in mind are likely Chilean or Colombian or Nicaraguan, the tragedy she expresses is global, and the victims could just as well have been Bosnian or Cambodian or Rwandan.

The exhibition concludes with A Flor di Piel, a piece she has created before, in 2011–12 and in 2014. In it, thousands of rose petals are stitched together, creating a kind of carpet or shroud on the floor, measuring some 20 by 40 feet. The petals now are a lustrous brown, and though they are transitioning from life to another state, they will not disappear altogether.

“Doris Salcedo” is at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, February 21–May 24, 2015. It will travel to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, June 26-October 7, 2015, and to the Perez Art Museum in Miami, May 6-October 23, 2016.