Art & Exhibitions

Child’s Play: How Exhibitions Have Increasingly Become Playgrounds For Adults

Art exhibitions increasingly cater to the under 18 set.

Photo: Courtesy of Public Art Fund.

Art exhibitions increasingly cater to the under 18 set.

Yevgeniya Traps

Hungry Castle’s latest Nicolas Cage themed bouncy castle.

Photo: Courtesy of Hungry Castle.

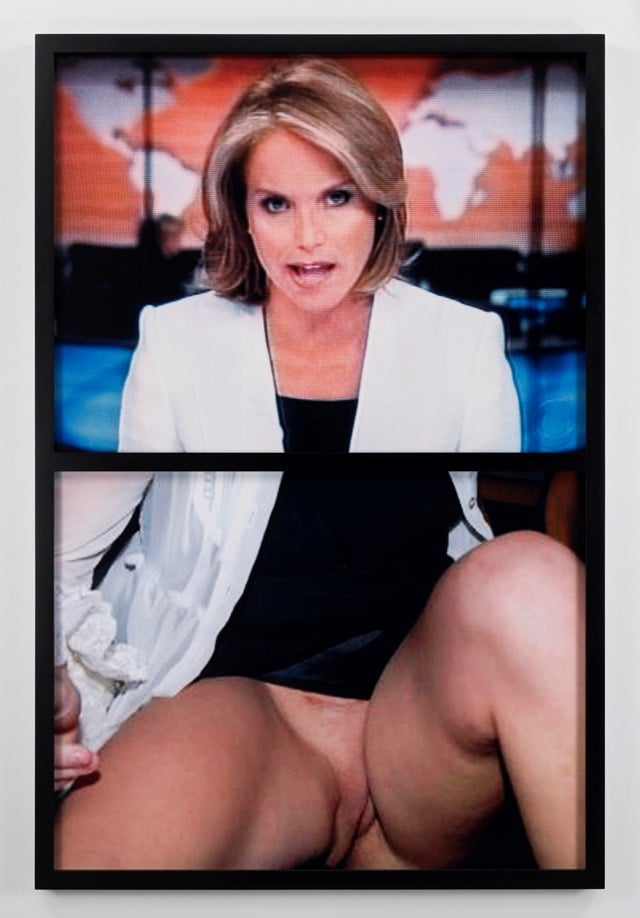

One of my most anecdotable museum visits happened a few years back at PS1: standing in front of Jonathan Horowitz’s CBS Evening News/www.Britneycrotch.org (2008), an aggressively hip uncle type was awkwardly explaining to his eight- or nine-year-old charge why it was he could see, in rather intimate detail, Britney Spears’s crotch.

The paparazzi came up, naturally, as did the fact that women occasionally choose to forego undergarments and how this might become problematic when exiting a vehicle. There may have been mention of Britney’s mental state around that time, perhaps by way of explanation for her not wearing underpants.

The museum had posted a notice at the entrance to the exhibit, entitled “And/Or,” which showcased the artist’s examination of “the cultures of politics, celebrity, cinema, war, and consumerism”: a small white card duly noted that “These galleries contain graphic imagery. Parent/adult discretion is advised.” In practice, however, adult discretion was difficult to manage, and not just for hip uncle types.

Jonathan Horowitz, CBS Evening News/www.britneycrotch.org (2008), two digital c-prints framed together. Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York.

In a New York Times op-ed, Fred A. Bernstein railed against the museum’s subtlety. Having failed to notice the “discretion” admonishment, Bernstein had very nearly exposed his seven-year-old twin sons to Britney’s privates, and he was incensed. Although he acknowledged and lauded the museum’s right to “show vulvas in extreme close-up” and disavowed censorship, he felt no less strongly that parents must receive adequate warning regarding an exhibition’s contents.

Leandro Erlich, Swimming Pool (2008).

Photo: Courtesy of MOMA PS1.

Bernstein noted that what made the whole thing more galling was the fact that, even as PS1 was blithely displaying gynecological-grade images, it was luring unsuspecting kids and their credulous parents with Leandro Erlich‘s installation Swimming Pool, a nifty bit of illusion in the museum’s Duplex gallery that allowed visitors to act out underwater scenes in what appeared to be the deep end of an indoor pool.

Bernstein’s article was called “Adult Art,” which in retrospect seems elegiac. If, in 2009, a parent could bemoan the likelihood of a museum trip ending in impromptu explicitness, in 2015, things are decidedly more anodyne.

Art institutions around New York are posting warnings galore, even when it is unclear what content might be inappropriate for some viewers, all the while increasingly offering exhibitions seemingly tailor made for toddlers, both actual and at-heart.

Installation view of Yayoi Kusama, Give Me Love (2015).

Photo: Courtesy of David Zwirner Gallery, New York.

At David Zwirner’s space on West 19th Street this spring, Yayoi Kusama’s show Give Me Love included The Obliteration Room (2002), an all-white domestic environment that would be, during the course of the show’s run, covered in colorful stickers. The long line to get into the gallery revealed a stampede of children, all waiting for the chance to be obliterated.

They also waited for the chance to have the experience captured for Instagram posterity, too. There are currently 4,485 posts (and counting) on Instagram tagged #obliterationroom.

Or take this summer’s Please Touch the Art, Jeppe Hein‘s interactive installation at Brooklyn Bridge Park, which most prominently features a water-based work called Appearing Rooms, where visitors can experience “walls of water that create rooms which appear and disappear,” as it states on the Public Art Fund’s website. This is arguably an even more child-friendly descendant of the Rain Room, which was shown at MoMA two summers ago. (Hashtagged Instagram posts: 20,677.)

Don’t get me wrong: I like Kusama. And I wanted to take my own toddler to see The Obliteration Room, though not badly enough to make her stand in a line that reminded me of trying to buy sugar during the late-Soviet sugar shortage. And I will probably take her to Please Touch the Art and marvel at the mechanics that allow you to enter a fountain and remain dry. This is not an “Against YA“-type of manifesto.

And yet: something is lost when art becomes touchable—amenable to pleasure and pleasure alone.

Quality and difficulty need not—do not—go hand in hand. But there is something oddly inaccessible in works that are pure whimsy, pure sweetness, and pure delight. Throughout her career, Kusama has been interested in the ways in which the artist might obliterate herself, and some of her work has made it possible for the viewer to experience some of this obliteration, to feel herself a tiny part of a vast universe, to simultaneously marvel and shudder.

The Obliteration Room, however, made it possible to paste colorful circles on walls and tables and other people and then to post pictures of the pasting for everyone to see. Which is a fun thing to do on a summer afternoon, but it is little more than that.

The paradox of so much interactive art, the sort of art that seems at least half deliberately designed to make children of us all, is that it forecloses engagement. You can touch the art, but it doesn’t touch you.

Jeppe Hein, Modified Social Bench NY #06 (2015).

Photo: Courtesy of Public Art Fund.

There is joy to be had, surely, in sticking an explosion of pinks and blues and oranges on white walls, of running headlong into curious fountains. But there is joy too in confusion, disorientation, the aesthetic silence of a work that cannot be easily posted online or explained in words.

Susan Sontag famously called for an erotics of art in place of hermeneutics: she wanted feelings, sensations—a sort of profoundly felt connection with art. But Sontag wanted rigor, too. Look at what you are looking at, she implored. See it as it really is.

On view at MoMA right now as part of Scenes for a New Heritage: Contemporary Art from the Collection is Nalini Malani’s Gamepieces, a shadow play/video piece that has the charm of a childhood summer evening coupled with the impact of lived history. Projecting drawings of various creatures and Hindu gods and goddesses onto found footage of atomic bomb testing, Malani’s work is at once full of magic and grace and vigor, a lullaby that wakes us up and then keeps us going.

Be a child, by all means. But be an adult, too. What we need right now is to be able to be both at once.

Nalini Malani, Gamepieces (2003-2009).

Gift of the Richard J. Massey Foundation for Arts and Sciences.

Photo: Courtesy of MoMA PS1/ © 2015 Nalini Malani.