Reviews

Museo Jumex Surveys ‘Fake News’ Pioneers General Idea

Their genius was to pinpoint culture’s endless feedback loop.

Their genius was to pinpoint culture’s endless feedback loop.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

A set of screen-prints from the first Latin American retrospective of the legendary Canadian art collective General Idea, currently at Mexico City’s Museo Jumex, perfectly illustrates how a well-turned sign can tame real-life inequities. Titled “Fear Management,” it consists of eight sarcastic escutcheons that feature pizzle-shaped penises, cartoon skulls and lesion-like stains invoking the 1980s AIDS crisis.

Their lesson couldn’t be more timely: if you can picture it, name it, or, better yet, draw it funny on a placard, the act turns even the greatest injustices into a rallying cry.

Finding humor in the darkest situations was one of the hallmarks of General Idea, a pioneering group of Canadian conceptualists and media-based artists that transformed the viral inanities of late twentieth century popular culture into a playground for razor-sharp ironies. Formed in Toronto in 1969 by AA Bronson (born Michael Tims), Felix Partz (born Ronald Gabe) and Jorge Zontal (born Slobodan Saia-Levy), the group lived and worked together for 25 years, dividing their time between Toronto and New York.

The trio officially ceased joint art activities in 1994; that was the year Partz and Zontal died from AIDS-related illnesses, a scourge they worked hard to help destigmatize.

Inspired by late ‘60s psychedelia, free love, student revolts and the medium-is-the-message credo of Canadian theorist Marshall McLuhan, General Idea cribbed both its collective and individual identities from materials they had closest at hand—art and mass culture. Their use of personal monikers, for one, was lifted from pseudonyms widely employed by artists active in the conceptual global mail-art networks of the 1970s.

Similarly, the group’s artistic handle echoed the trade names of giant corporate entities, like General Mills and General Electric. Viewed sardonically, their faux-commercial alias fit the collective’s culture-baiting, piss-taking spirit like a snug “Bull Shirt” T.

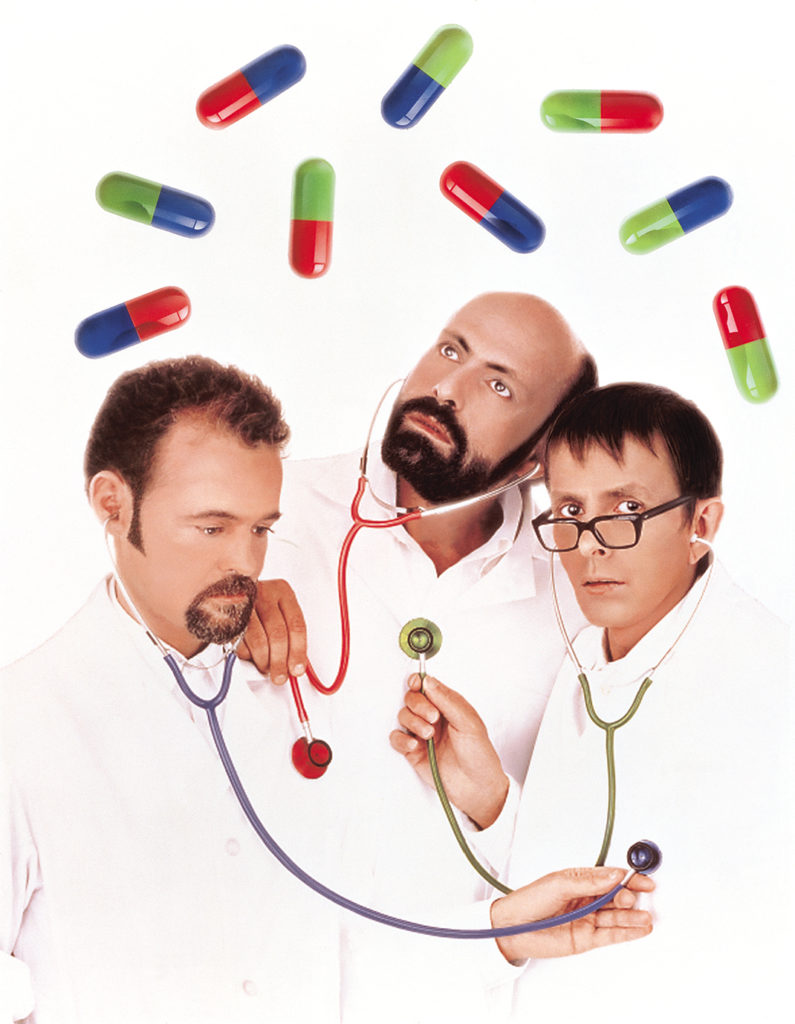

Playing Doctor, 1992 Cromogenic print, Estate of General Idea, Toronto

Because General Idea’s artworks participated in rather than directly opposed mass culture, the trio became pioneers in the field of what we call “fake news” today. In 1972, for example, General Idea launched File Magazine, a publication that served as a global bridge for Toronto’s burgeoning arts scene (collaborators included the novelist William S. Burroughs, the art collective Art & Language, and the rock group the Talking Heads) while also mimicking the breathless celebrity twaddle of print media. The publication looked remarkably like Life Magazine—“file” is an anagram of “life”—so much so, in fact, that Life’s publisher threatened to sue.

As General Idea’s members explain in “Pilot,” a 1977 mockumentary-style video that introduces their survey at the Museo Jumex, the cease and desist letter they received accused the artists of “simulation of Life”—nothing more and nothing less.

Curated by Agustín Pérez Rubio, artistic director of Argentina’s Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA), “General Idea: Broken Time” represents a south of the border version of an alternative museum universe. Organized by both the Museo Jumex and MALBA, the show presents an influential group of North American artists whose oeuvre—while widely recognized and exhibited in Europe—has largely been ignored in the US. Inexplicably, the exhibition is not scheduled to travel northwards, much like the critical blockbuster “Andrea Fraser: Le 1%, c’est moi,” currently on view across town at the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporaneo.

After Donald Trump’s recent executive orders limiting human and cultural traffic to the US from seven predominantly Muslim countries—as well as his threat to build a wall along the border with Mexico—provocative art exhibitions like these face mounting challenges. In the future, it’s possible North American art lovers will be increasingly obliged to travel south to see important exhibitions by controversial artists from Canada and the US. Cue the theme from “the Twilight Zone.”

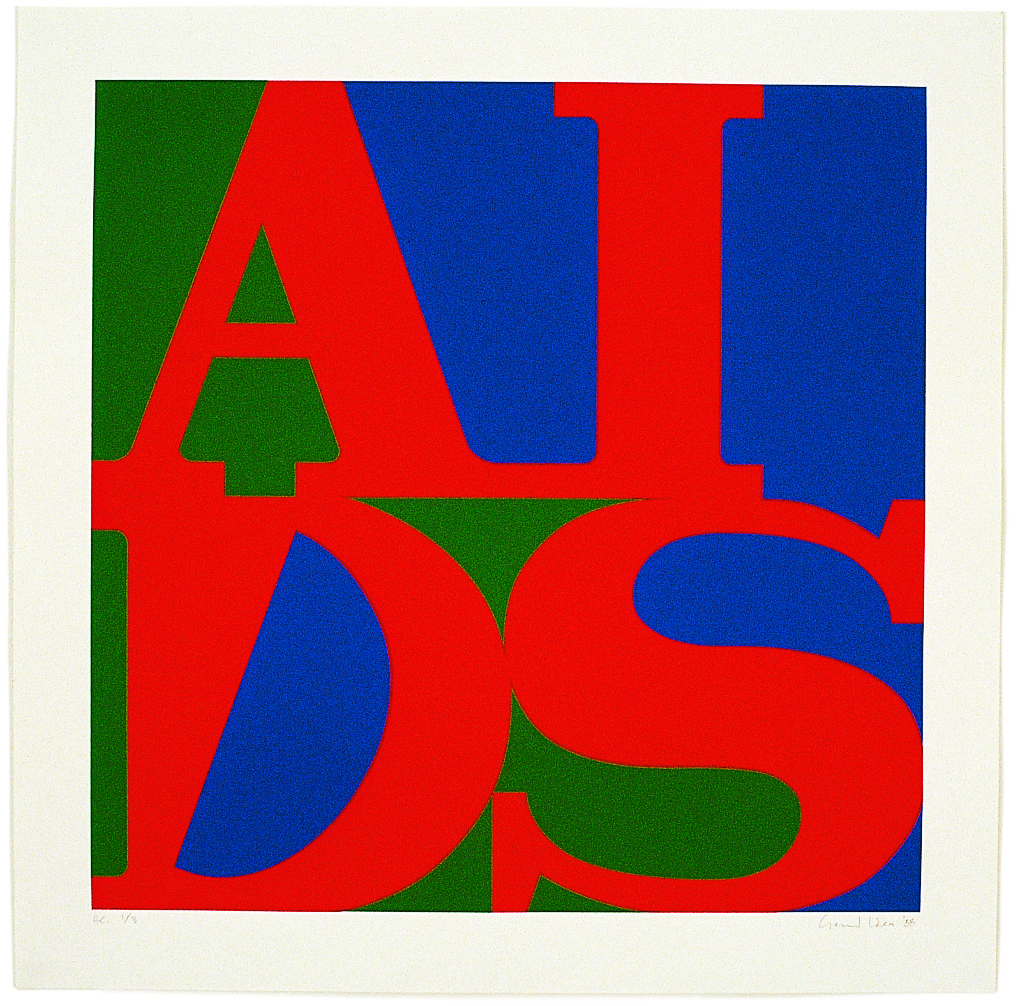

AIDS, 1987, Screenprint on paper, Estate of General Idea, Toronto

Featuring more than 120 pieces covering every possible kind of media, including stamps, men’s skivvies, giant inflatables resembling antiviral capsules, painting, photography, video, installations and a vast quantity of editions generated through Art Metropole, the group’s multiples publisher, General Idea’s Latin-America-only survey can best be described as a topsy-turvy plunge into fin de siècle US cultural politics. If the title of the exhibition, “Broken Time,” alludes to what the late Joseph Campbell would have called “mythical time”—the curator refers to the group’s ability “to create something that already existed but had not yet been created”—the show itself points to these artists’ evolving attempt to turn art into a high-powered communications weapon.

Despite their self-identification as artists, the group’s activities often look like those of wacky public relations company or advertising firm. Take the trio’s pivotal 1970 beauty-contest project Miss General Idea—a stripped down allegory of how to get ahead in the art world—which they reprised in a set of ongoing audience-participatory performances that upped the ante on both the pageant’s absurdity and mass appeal. Later, in 1987, the group took the acronym for acquired immune deficiency syndrome and turned it into a logo by retooling artist Robert Indiana’s famous 1966 piece LOVE. In no time, their re-creation became a wearable rallying cry emblazoned on millions of activist surfaces (the show includes wallpaper, t-shirts and a poster campaign that targeted major US cities).

General Idea’s genius, as demonstrated in these and other works animating Museo Jumex’s excellent retrospective, was to pinpoint culture’s endless feedback loop—wherein art imitates life in the same way that life imitates art. This exhibition contains many takeaways, but the best for our other-planetary present is this: besides furnishing “fake news,” cultural ingenuity can do the impossible. Don’t believe me? It once turned AIDS into LOVE, and vice versa.