It wasn’t Columbus Day for everyone in the US this week. Many eschewed the national holiday to celebrate Indigenous Peoples Day, choosing instead to honor the histories of Native Americans and other indigenous peoples around the world. Similarly, the artist Hew Locke has found a new way to reveal overlooked or marginalized histories—by re-imagining the statues of dead white males who benefited from colonialism or the slave trade.

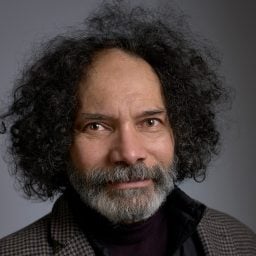

For Locke’s new series, which was unveiled today in New York, he has focused on the city’s increasingly polarizing public monuments. Through his photo-based work, memorials to George Washington, Christopher Columbus, and Peter Stuyvesant, and others become strange, fetish-like figures that seem burdened by their flawed reputations.

Rather than knocking the controversial sculptures off their pedestals, or banishing them from their prominent locations, the London-based artist’s creative response involves smothering images of the statues in layers of cheaply sourced, often garish or gruesome regalia. In so doing, he hopes to illuminate a past that is all too often glossed over.

His new show “Patriots,” which is his first at New York’s PPOW gallery, includes an image of a particularly repellant memorial that until recently stood in Central Park. The 19th-century surgeon, J. Marion Sims, is a Josef Mengele-like figure for many African Americans. The “father of modern gynecology,” Sims advanced surgery by experimenting on enslaved black women without an anesthetic.

“All of sudden the statue thing has become a hot topic,” Locke tells artnet News. “It is interesting because I used to pass these statues and wonder what people thought of them. Are they as benign as they appear?” Locke explains that in “Patriots” he is trying to draw attention to “the stories behind these guys.”

He developed the new series in the wake of the controversy surrounding Confederate statues in the South. He is familiar with the kind of memorials erected long after the Civil War in order to express white supremacy. Locke knows Atlanta, where his father lived, and he remembers seeing General E. Lee on a column in New Orleans when he took part in the city’s Prospect.3 Biennial in 2014.

Hew Locke, Columbus, Central Park (2018). Copyright the artist, courtesy of P.P.O.W.

Columbus’s and Sims’s statues have been in the firing line of late, but the inclusion of Peter Stuyvesant, the last Dutch director-general of the colony of New Netherlands, might surprise those unfamiliar with his biography. Locke, who says he would have been a historian if he had not become an artist, was interested in Stuyvesant because his anti-Semitism has been whitewashed.

“Unfortunately for him, when he got his job there were already Jewish people in New York,” Locke says wryly. Stuyvesant did his best to prevent synagogues being built in New York, and he made a major effort to stop Jewish further immigrants, he explains. “He didn’t like Catholics as well, and it is taken for granted that he didn’t like black people,” Locke says.

“I give them costumes made of plastic, metal, and glass beads that loosely refer to the slave trade. There are loads of skulls, particularly on Peter Stuyvesant’s statue, which are memento mori,” he says. Dressed in a suit of armor, which is sprayed in gold, the Dutch colonialist becomes “a baroque, very dark knight.” Locke enjoys the irony that Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s statue of Peter Stuyvesant is in Greenwich Village. Stuyvesant must be spinning in his grave.

Locke’s interest in the power of statues and empire builders goes back to his childhood in Guyana. “There was a Queen Victoria statue that I passed every day to get to school,” he recalls. “It had bits knocked off it and was lying on its side at the back of the Botanical Gardens, essentially dumped. That was a complete shock.” The statue was blown up during Guyana’s struggle for independence, but when Locke returned after relations with Britain had improved, he found that the statue had been restored and returned to its place.

The various ways bits of history are celebrated, dumped, and then reappraised has been central to his work. Since the 1980s, Locke has been re-imagining public sculptures of colonial-era heroes by embellishing large-format photographs of them. They have included generals, philanthropists, slave traders, and Queen Victoria. (He also creates elaborate sculptures, sometimes of fantastical boats. One such installation, The Wine Dark Sea, H, 2016, was acquired by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art last year.)

Next spring, the artist’s major survey opens at the Ikon Gallery in the English city of Birmingham. It could be the first time Locke decorates an actual public sculpture rather than an image of one. The director of the Ikon Gallery, Jonathan Watkins, tells artnet news that it has secured planning permission for Locke to temporarily turn the statue of Queen Victoria in Queen’s Square into a “Voodoo Queen.” Watkins says that there has been a generally positive response to the proposal. Now, he hopes funders will step forward to help make it a reality.

“Hew Locke: Patriots,” PPOW, October 11 through November 10, New York.

“Hew Locke: Here’s the Thing” (working title), Ikon Gallery, March 8, 2019, through June 2, 2019, Birmingham, England.