Analysis

Is Camille Claudel Finally Out from Under Rodin’s Shadow?

The 19th-century French sculptor is a top seller. Who knew?

The 19th-century French sculptor is a top seller. Who knew?

Eileen Kinsella

Camille Claudel The Waltz (executed 1892, cast 1893), sold for a record $8 million at Sotheby’s London in June 2013. Photo: Courtesy Sotheby’s

On reviewing the list of the most expensive women at auction, alongside the more predictable names like Georgia O’Keeffe, Joan Mitchell, and Cindy Sherman (artists who have long dominated the field), we were somewhat surprised to see the name of a lesser known 19th-century French sculptor, Camille Claudel.

Claudel has long been best known for her connection to her teacher Auguste Rodin, with whom she endured a stormy decade-long love affair before finally leaving him around the turn of the century to work on her own. While she never achieved the recognition that he did, or received major commissions, like Rodin’s Gates of Hell, she was a respected artist during her lifetime. While she fell into relative obscurity following her death in 1943, there was a resurgence of interest in her work in the late 1980s and 90s. And her market has only grown stronger.

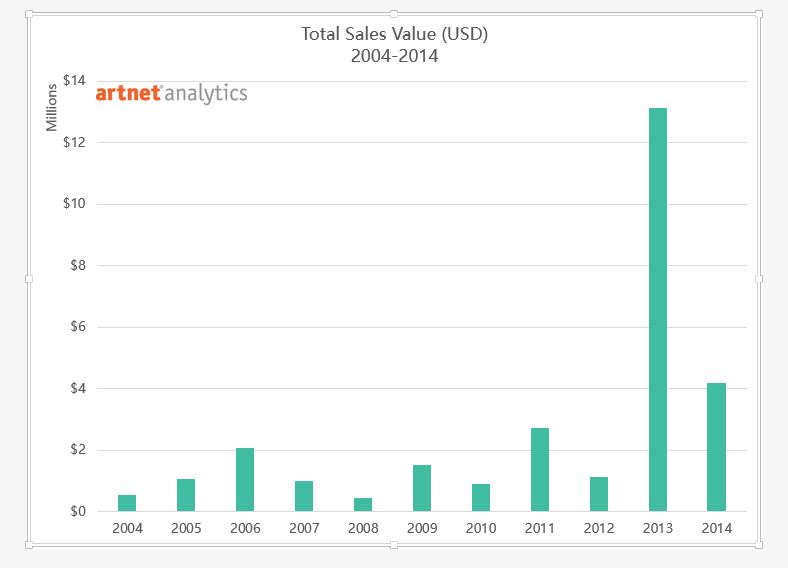

In June 2013 a new record at auction was set for Claudel at Sotheby’s London when The Waltz (executed in 1892 and cast in 1893) sold for $8 million (£5 million), more than double the high £2 million estimate. Just a month before, in May 2013, another version Waltz, conceived in 1895 and cast in 1905, had sold at the evening Impressionist sale at Sotheby’s New York for $1.9 million, well above its $800,000–1.2 million estimate.

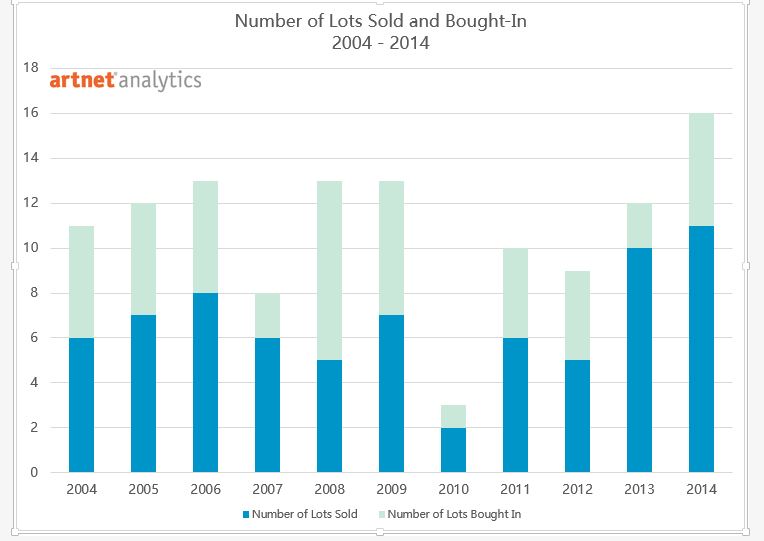

That year Claudel’s auction volume leapt to $13.1 million, compared with $1 million in 2012. Furthermore, the number of works on offer grew to 12 in 2013 (of which 10 were sold). In 2012, nine were on offer, of which five were sold.

Auction experts point out that Claudel has been held in high esteem as a sculptor for decades, and interest in her work has been steadily rising. However, her market and oeuvre are inextricably linked to Rodin. Also integral to understanding some of the ups and downs in her market is the fact that she spent the last 30 years of her life in an insane asylum in France against her will, and at the behest of her brother, the poet Paul Claudel. She stopped working altogether during that time, which was, by all accounts, miserable and harrowing.

“I think in looking at Claudel, one has to look at her through the prism of Rodin, because of their relationship, and her sad fate confined to an asylum” said Simon Stock, senior international specialist in Sotheby’s Impressionist and modern art department in London. “Whether that’s fair or unfair, one would look at the context of the fact that she was a very accomplished sculptor but has been overshadowed by Rodin, even though she has always had a strong following.”

In terms of highest lots sold, Rodin’s market, in comparison, isn’t exceedingly that far off. The record for Rodin is just under $19 million, which was achieved for the bronze Eve, grand modele-version sans rocher (1881-cast in 1897) at Christie’s New York in May 2008 (with an estimate of $9-12 million). But it was just a year before that Rodin hit a price above $8 million, when Iris, messagère des dieux (ca. 1890, casting 1902-1905) sold at Sotheby’s London for $9 million (£4.6 million). Of course, their output was vastly different. About 3800 works by Rodin have come up for auction compared to Claudel’s roughly 250.

To that end, when interest in Rodin rises, Claudel’s career and market usually benefit as well, he notes. Last year, the Eifman Ballet “Rodin” came to London and toured Europe. The show explored Claudel’s connection with Rodin as well as the sometimes disputed notion that he was dependent on her ideas. It caused “quite a bit of focus on Claudel,” said Stock.

Camille Claudel, La sirène ou La joueuse de flûte (ca. 1900–1905).

Photo: artnet

Claudel garners a fair share of attention on her own; including a current solo show (through February 8) at La Piscine (the museum of art and industry) in Roubaix, France. Juliette Binoche played the beleaguered artist in the critically-acclaimed film Camille Claudel 1915 (2013), which chronicles just three—albeit extremely bleak—days during the artist’s confinement at the asylum as she waits for her brother to arrive for a visit. An earlier 1998 film, Camille Claudel starring Gérard Depardieu and Isabelle Adjani as the artist, also explored their tormented relationship.

“I think there has been a bit of a trend for some time now and certainly an improving market including the huge price in 2013 for the the monumental Waltz,” said David Kleiweg de Zwaan, vice president and specialist in Impressionist and modern art at Christie’s. “A lot of her most commercial, or desirable works were produced in the the very late 19th century. One could say that is when she achieved real maturity,” he said, adding that her last known work dates to about 1905, before she was committed and stopped making art altogether.

“All of the top prices have been achieved in the last ten years,” said Kleiweg de Zwann, noting that her market “continues to become strong.” The highest Claudel lot sold by Christie’s to date is L’abandon, which went for $1.7 million (£1.1 million) on an estimate of $1.1–1.4 million at its Impressionist and modern evening sale in London in February 2013. Conceived in 1886, the bronze version was cast circa 1905, and was the second in an edition of 25, of which only 18 were cast.

Camille Claudel L’abandon. Photo: Courtesy Christie’s

Stock pointed to another strong price achieved just this past summer when Torse de femme acroupie (conceived in 1885 and cast in an edition of two, likely in 1913 at a foundry under the instruction of Philippe Berthelot), sold for $930,739 (£542,500) at Sotheby’s London (its estimate was $424,000–594,000). “The price of the torso was quite remarkable as there wasn’t anything easily or traditionally recognizable as Claudel. But it was a beautiful rare casting with a good provenance,” said Stock.

The artnet Price Database lists more than 200 auction results for Claudel, all of which are sculpture, with prices starting at $5,000 for a later cast of a work. The number of buy-ins seems significantly high, with roughly half of the works labeled as “bought in” or unsold.

As for the renewed interest in Claudel’s work, Kleiweg de Zwaan said, “People were really revisiting the work and starting to understand it. We’re delighted to see that it’s continuing and doing everything that we can to sustain interest.”