Art & Exhibitions

Dallas Museum Gets $500,000 Grant for Rare Jackson Pollock Painting Show

This will be the show's last venue.

This will be the show's last venue.

Sarah Cascone

The Dallas Museum of Art (DMA) has received a $500,000 grant to support its current exhibition, “Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots,” which includes masterworks by the artist that have not been seen by the public for over half a century.

“It took many many grants and donations to pull this show off but this one is pretty spectacular,” DMA senior contemporary art curator Gavin Delahunty told artnet News in a phone interview.

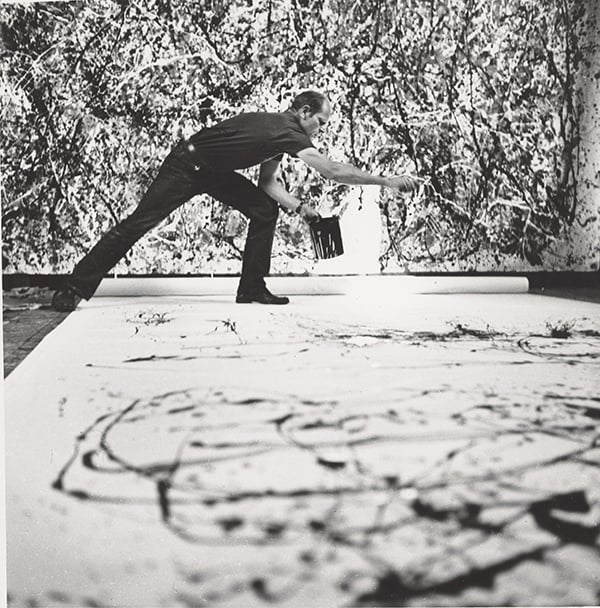

Hans Namuth, Jackson Pollock’s studio.

Photo: ©1991 Hans Namuth Estate

Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, the University of Arizona.

The money comes from the Texas Commission on the Arts as part of its 2016 Cultural District Project Grants, which will give out $1.5 million through the new Arts Respond Cultural District Project grants for Texas arts institutions promoting cultural tourism. The DMA received by far the largest grant among this year’s 20 recipients.

Noting that it was “highly unusual” for an institution to receive the full amount of funding requested in its grant application, Delahunty says the grant “signals a confidence in Dallas and a confidence in the museum.” Since opening November 20, the show has already had 10,000 visitors.

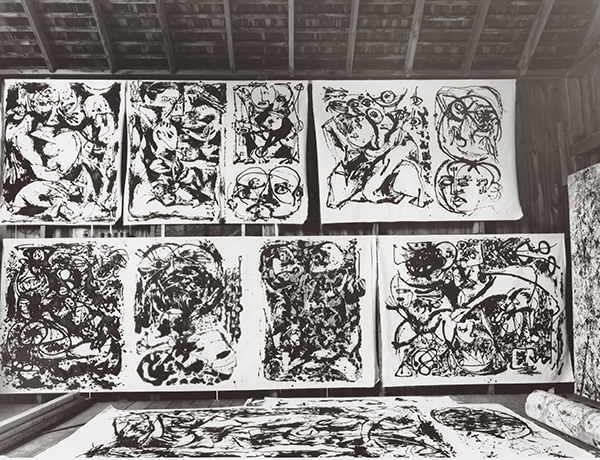

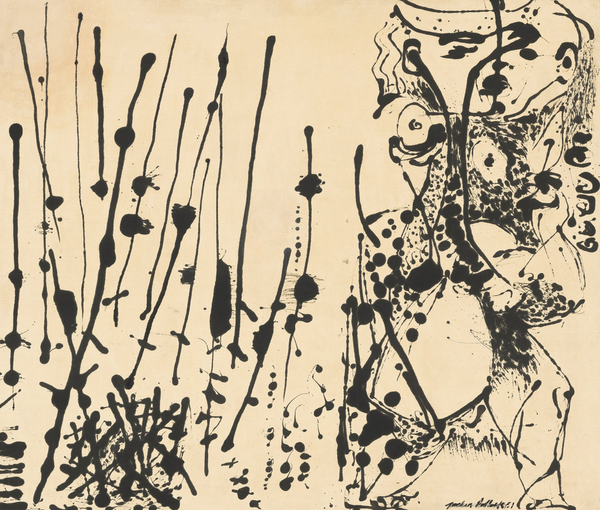

Jackson Pollock, untitled (1951).

Photo: courtesy the Dallas Museum of Art.

The exhibition contains plenty of Pollock’s iconic drip paintings, and 70 works overall, but is organized around his somewhat-overlooked black paintings (1951–1953), a series that Delahunty noticed was being shown in decreasing volume. “It was like a red rag to a bull,” joked the curator, who resolved to bring together the largest selection of such works (31) ever shown.

The show’s title, “Blind Spots,” is a reference to the little-studied black paintings, as the exhibition looks to examine Pollock’s career from a broader angle, beyond the classic works that made him a household name.

Jackson Pollock, Echo Number 25 (1951).

Photo: courtesy the Dallas Museum of Art.

First shown at New York’s Betty Parsons gallery, the 31 black paintings on view mark a dramatic departure from Pollock’s iconic drip paintings made between 1947 and 1950. Abandoning the excruciating detail of the earlier paintings, Pollock executed the new works using just enamel on raw canvas, which absorbs the paint like a sponge.

“That gesture was a revelation to many many artists,” including Helen Frankenthaler and Robert Rauschenberg, said Delahunty, but “critically and commercially they were unsuccessful. Ultimately the market wanted more of the same, more of the classic drip paintings.”

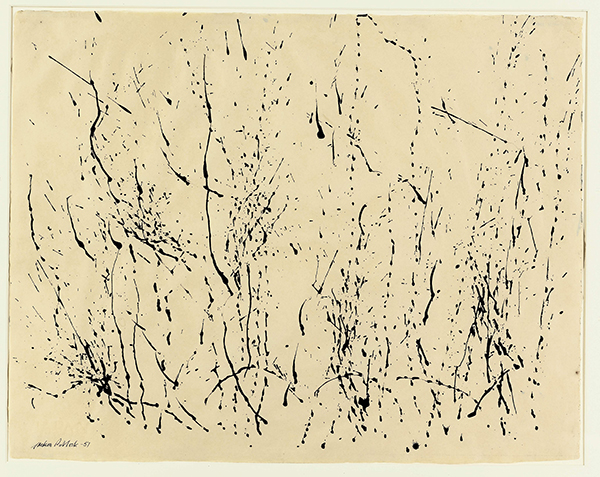

Jackson Pollock, untitled (circa 1949–50).

Photo: courtesy the Dallas Museum of Art.

Pollock’s willingness to defy expectations, even after the fame and success that landed him on the cover of LIFE magazine in 1949, is “a testament to his ambition as an artist and his continual pursuit to push himself forward,” Delahunty said. Though it may not be written in the art history books, the black paintings “opened an entire new chapter of picture making.”

Delahunty originally organized the exhibition for Tate Liverpool, where he was head of exhibitions and displays from 2010 to early 2014. The Dallas edition, which marks only the third major Pollock museum show held in the US (the first two being held in 1967 and 1998), is even larger than the original incarnation, which attracted nearly 50,000 visitors.

Jackson Pollock, Number 7 (1951).

Photo: courtesy the Dallas Museum of Art.

The DMA will be the show’s last venue. “I could have sent this exhibition to every major museum in the world,” said Delahunty, were it not so difficult to secure loans of the works. “You have to wait another fifty years to see this exhibition again.”

“Anyone who has the good fortune to be a custodian of a Jackson Pollock are incredibly protective of that work,” he explained. “It literally takes years of negotiations and conversations to accumulate works for a project of this scale.”

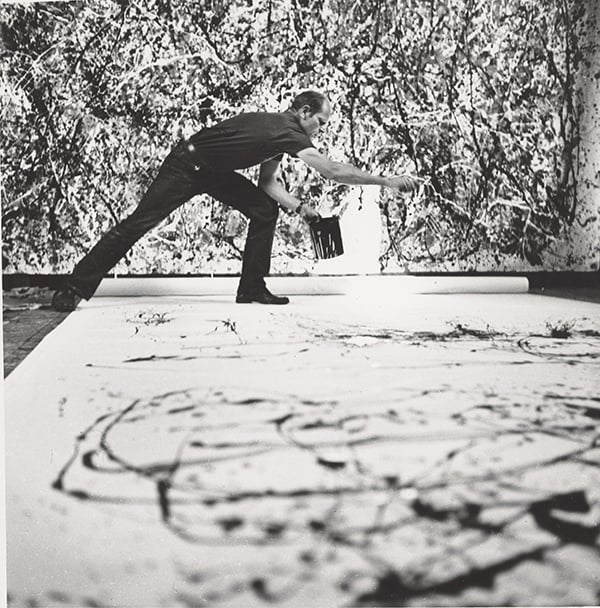

Hans Namuth, Jackson Pollock at work.

Photo: ©1991 Hans Namuth Estate

Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, the University of Arizona.

The Cultural District grant will help cover the ongoing costs of operations for the show. “It’s an incredible valuable body of artworks and that needs very careful attention” and heightened security, noted Delahunty, citing the “cast of literally hundreds of people” involved.

Receiving funding after an exhibition is on view may be slightly unorthodox, but the grant, he says, “couldn’t come at a better time.”

Jackson Pollock, Number 3 (1952).

Photo: courtesy the Dallas Museum of Art.

“Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots” is on view at the Dallas Museum of Art November 20, 2015–March 20, 2016.