Art & Exhibitions

‘Researching It Was Unbearable’: Turning 80, Judy Chicago Is Taking on Mortality, Extinction, and the End Times in Her Latest Work

The artist, who turns 80 next month, has been thinking a lot about death.

The artist, who turns 80 next month, has been thinking a lot about death.

Sarah Cascone

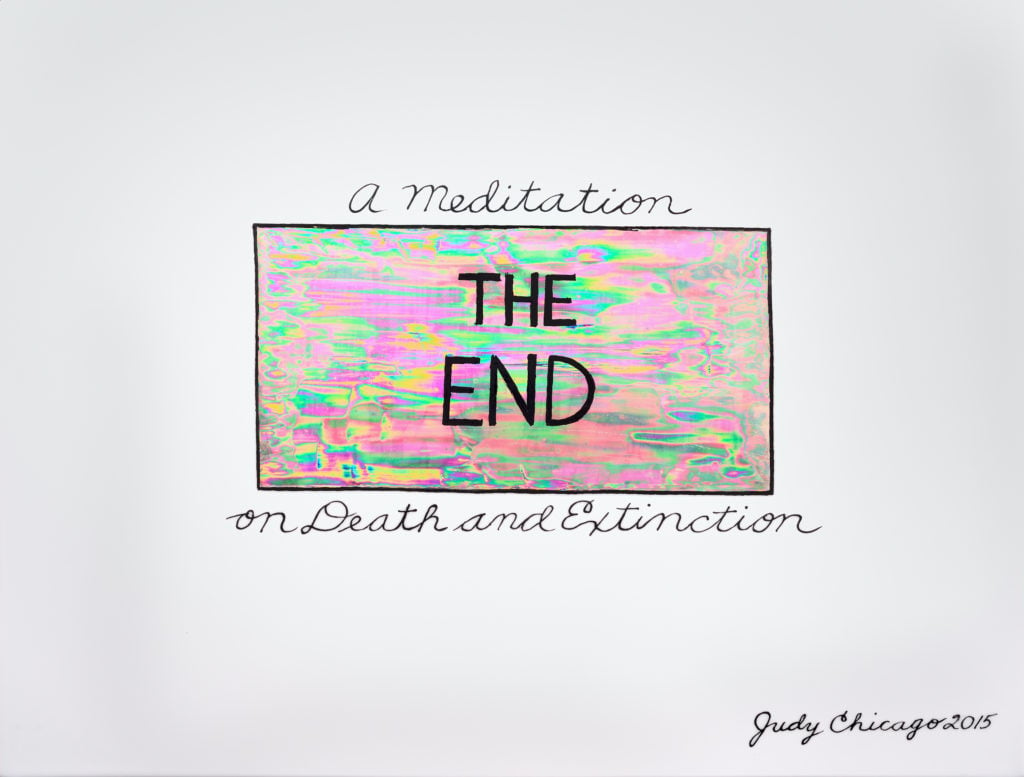

Next month, pioneering feminist artist Judy Chicago will turn 80. With that milestone fast approaching, Chicago, best known for her landmark installation The Dinner Party, has been making a new body of work confronting mortality and extinction, which will debut at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC, this fall.

“I’ve always been very conscious of my own mortality, and I can’t believe I’ve lived this long,” Chicago told artnet News. “I never expected to live out a full life.”

Chicago’s 80th birthday weekend will also mark the opening of her new Through the Flower Art Space in Belen, New Mexico, where she and her husband, photographer Donald Woodman, have lived for the past 27 years.

The small museum will be the centerpiece of Belen’s new Becker Avenue Art and Culture District. To celebrate the two-day opening, Chicago will debut a new fireworks piece, titled The Birthday Bouquet for Belen, on July 20, her actual birthday.

Judy Chicago. Photo by Carl Timpone courtesy of BFA.

“It’s a sophisticated oil painting technique except that you fire the layers onto the glass individually,” Chicago said. “Painting on glass is very exacting and challenging.” (Each painting starts with an underlying layer of white paint in order to make the image visible on the black glass.)

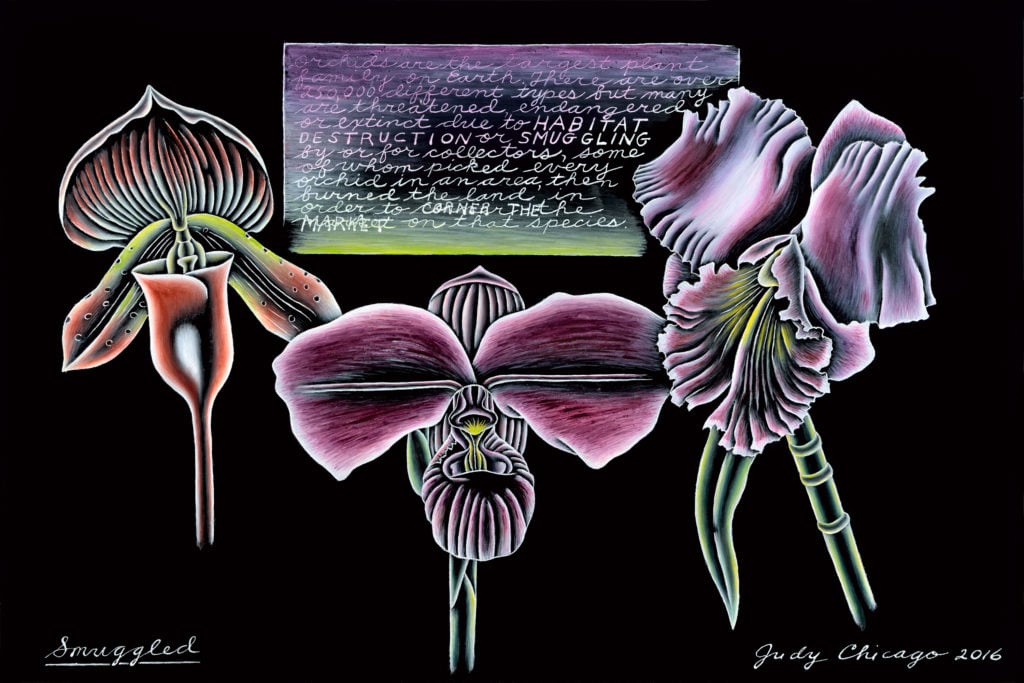

To prepare for the series, the artist did difficult research on subjects such as animal experimentation and the Holocaust. “Believe it or not, the section on mortality was easier to do than the section on extinction. When I really began researching, it was unbearable,” said Chicago. “We’re driving the human species and all other species to destruction.”

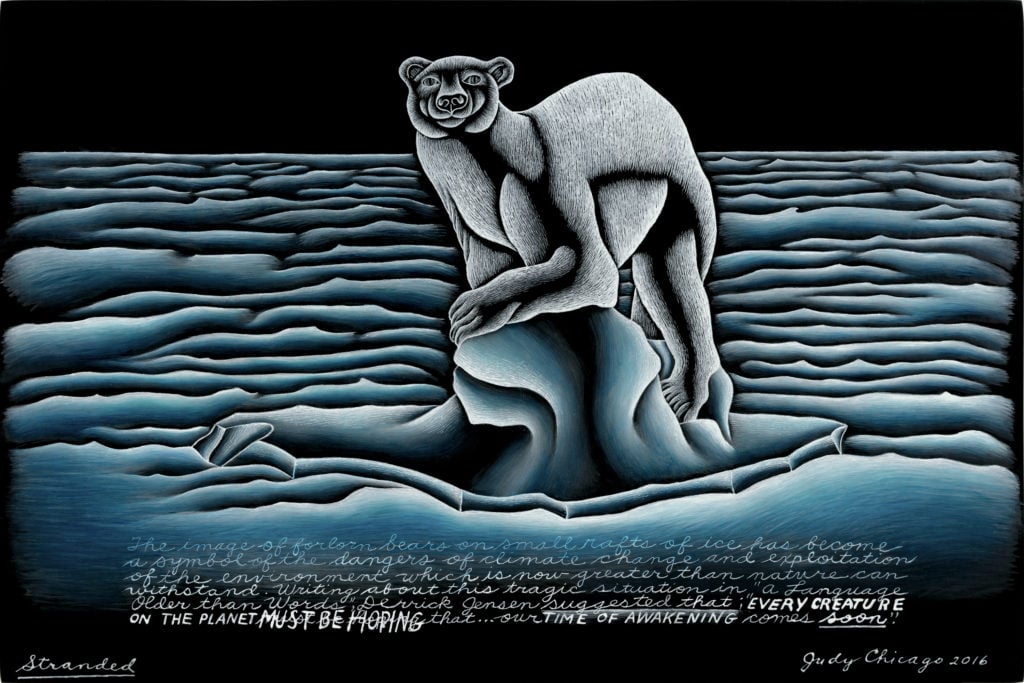

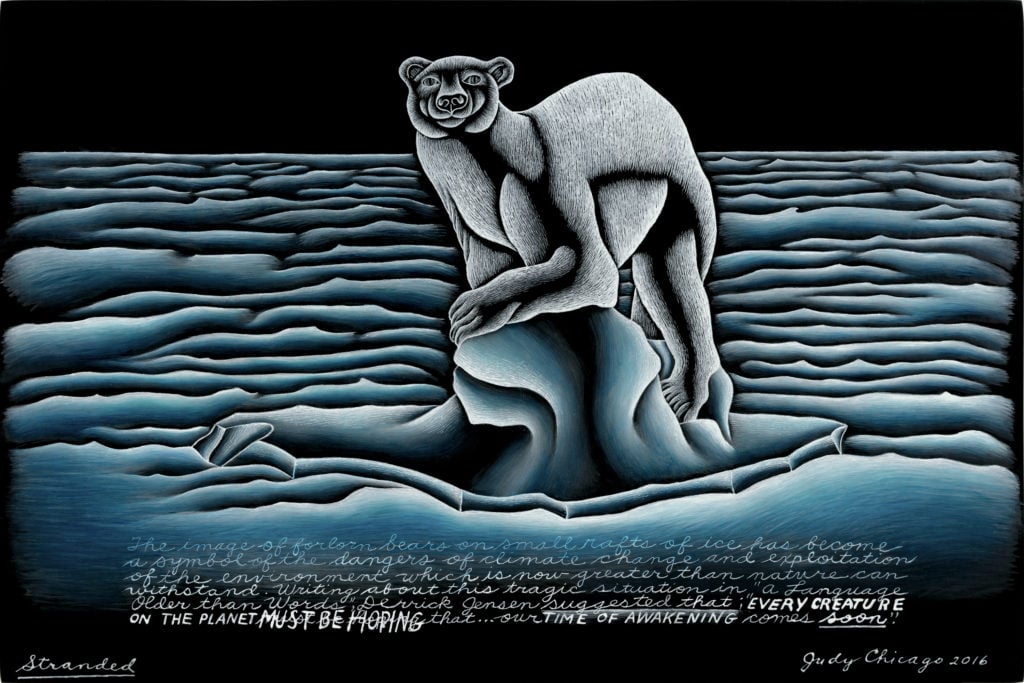

Judy Chicago, Smothered from “The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction” (2016). Photo by ©Donald Woodman/ARS, New York, courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco; ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS).

Chicago was three years in when she was inspired by a visit to the Museum of Modern Art in New York to see Jacob Lawrence’s “The Migration Series,” 60 panels inspired by the migration of African Americans from the south to the north beginning in the 1910s. “Although they were small, they were unbelievably powerful,” Chicago said. It reinforced her decision to work on a small scale for her new pieces.

“I deliberately wanted to go the opposite way of the art world: bigger, more impersonal work created by [other] people,” she said. “Because the subject matter was so personal and intimate, I wanted it to be in my own hand. I wanted it to go from my hand into other people’s hearts.”

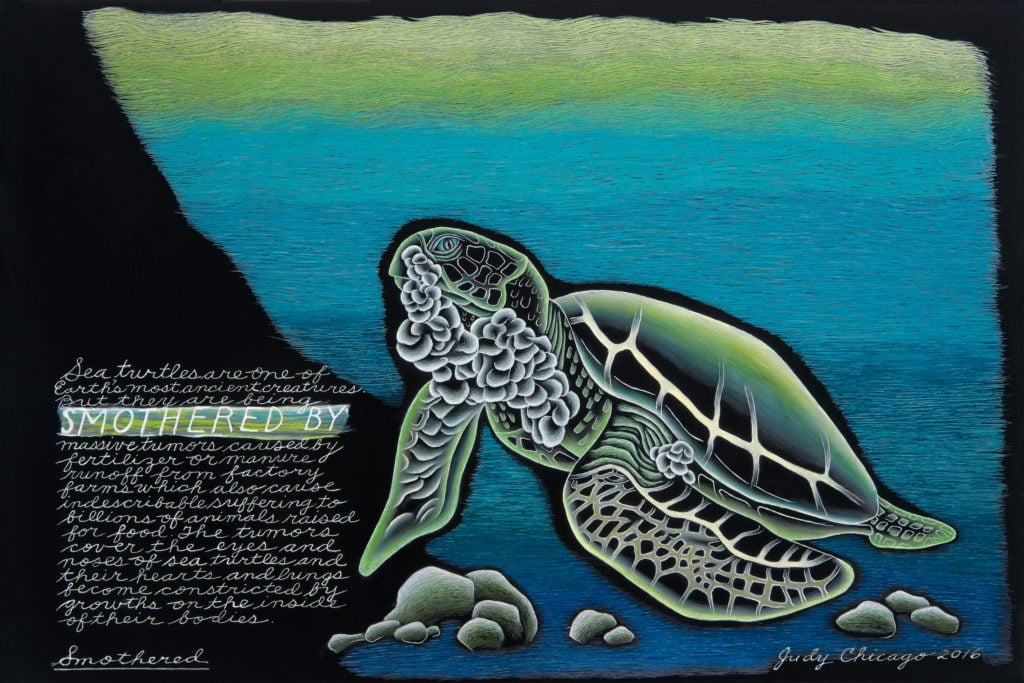

Judy Chicago, Title Panel from “The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction” (2015). Photo by ©Donald Woodman/ARS, New York, courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco; ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS).

Chicago sees her Through the Flower Art Space as another way of opening up. “I’m particularly interested in reconnecting art and community as a kind of alternative to the money-driven art world,” she said. “I lived here in order to have a certain amount of psychic privacy and space, but that’s going to change with the opening of the art space. Even though that’s difficult for me, I have to live my values.”

After an initial uproar among conservative members of the community who objected to the sexual themes in Chicago’s work, the project saw a groundswell of support. The mayor pledged to donate his annual salary to the space, and the town of 7,000 people raised $50,000 to help renovate the building.

Even the pastor who had been the most vocal opponent of the space had a change of heart, saying at a city council meeting that since the project was going forward it must be God’s will and perhaps “the opposition that was mounted helped people learn about the Through the Flower Art Space and was going to help it become a success,” Chicago said.

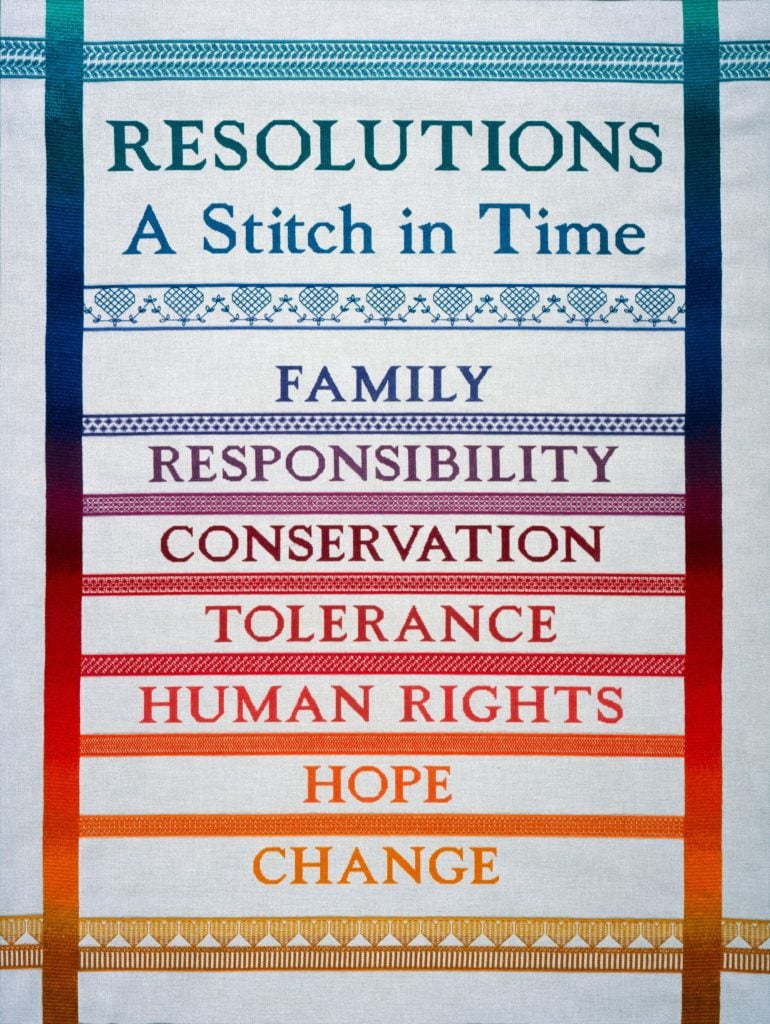

Judy Chicago, Needlework Sampler (2000), needlework by Pat Rudy-Baese, Jane Thompson, and Joyce Gilbert. Photo courtesy of Through the Flower.

It’s a small space, just 1,700 square feet, but it will include both a gallery and a research library. The opening exhibition includes photos by Woodman as well as works from Chicago’s last collaborative project, the needlework-based series “Resolutions: A Stitch in Time” (1994–2000). There will be monthly Flower Fridays with community programming, starting on August 23 with a talk with writer Jori Finkel, who featured Chicago in her new book It Speaks to Me.

On October 17, the Through the Flower Art Space will also offer access to the Judy Chicago Portal, which launches that day, offering public access to her archives, split between Schlesinger Library for the History of Women in America at Harvard, Penn State, and the National Museum for Women in the Arts. (A gift shop will feature select vintage projects as well as Chicago’s new line of limited edition art objects from Prospect NY. And just across the street, Jaramillo Winery will launch its line of Judy Chicago wines, with labels designed by the artist.)

The Prospect NY has released a new limited-edition collection of plates based on Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party. Photo courtesy of the Prospect NY.

Chicago has other major projects in the pipeline as well, including an exhibition in September with Jeffrey Deitch in Los Angeles of her early sculptural work. In October, New York’s Salon 94 will show Chicago’s preparatory drawings for “The End.”

And this past weekend, an exhibition of “The Birth Project,” Chicago’s series celebrating women giving birth—a subject rarely depicted in art history—opened at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, New Mexico. Showing this work again just as several states have passed restrictive abortion laws made Chicago reflect on how the issues she was tackling as a young feminist artist remain all too relevant today.

Judy Chicago, Birth from the Birth Project (1984), executed by Dolly Kaminski. Collection of the Albuquerque Museum, New Mexico. ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photo ©Donald Woodman/ARS, New York.

“Young women are going to have to fight the exact same battle women of my generation fought for: the right to control their own body,” Chicago said. “The celebration of birth, the investigation of birth, and the acknowledgment of the power of the female to create life that is in ‘The Birth Project’ has suddenly come up against this effort to control that power, to deny that power, [and] to punish that power.”

For Chicago, it’s gratifying to have so much renewed interest in her career. But there’s a certain amount of wariness to showing her new work. “The art world is only now getting up to my first three decades,” she said. “I have no idea what kind of reaction there will be—but I brought all of my skill, and my knowledge, and my aesthetic together on this work.”

See more works from “The End” show below.

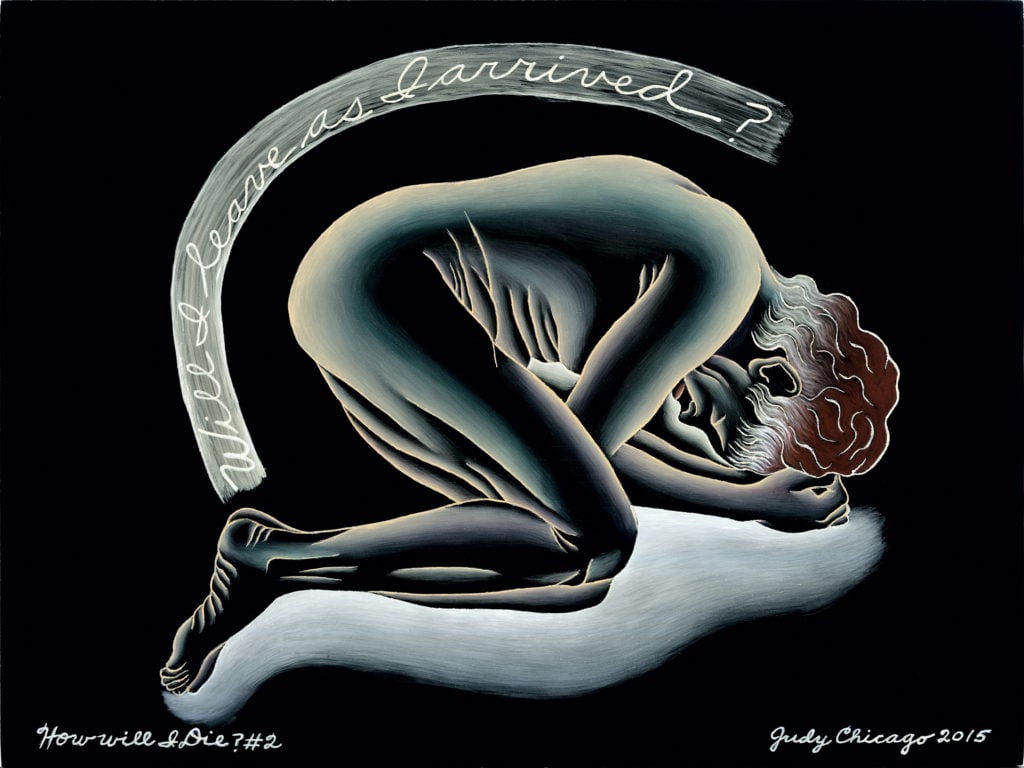

Judy Chicago, How Will I Die? #2 from “The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction” (2015). Photo by ©Donald Woodman/ARS, New York, courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco; ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Judy Chicago, Mortality Relief from “The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction” (2018). Photo by ©Donald Woodman/ARS, New York, courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco; ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Judy Chicago, Smuggled from “The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction” (2015). Photo by ©Donald Woodman/ARS, New York, courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco; ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

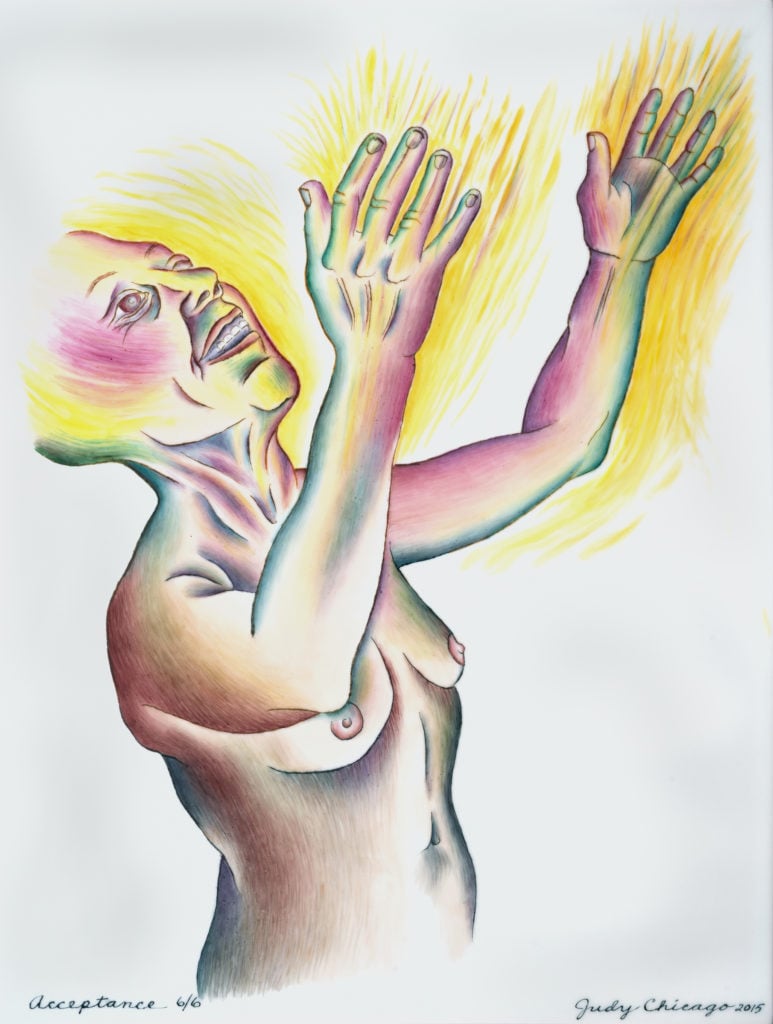

Judy Chicago, Stages of Dying 6/6: Acceptance from “The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction” (2015). Photo by ©Donald Woodman/ARS, NY, courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco; ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

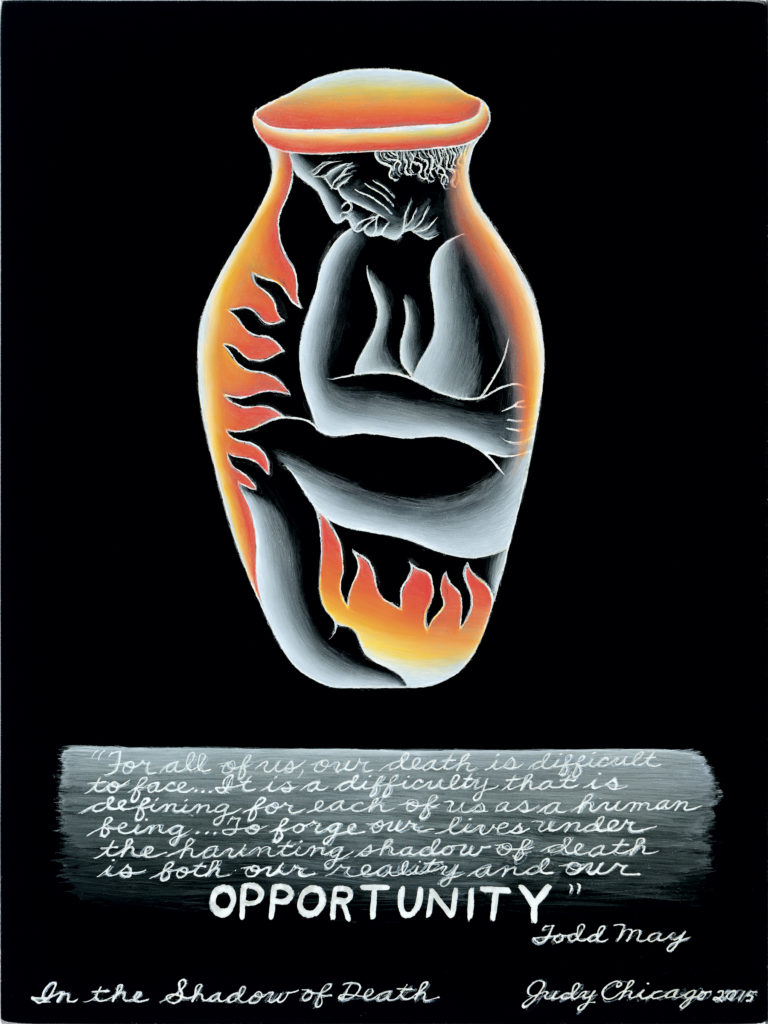

Judy Chicago, In the Shadow of Death from “The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction” (2015). Photo by ©Donald Woodman/ARS, New York, courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco; ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS).

Judy Chicago’s “The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction” will be on view at the National Museum of Women in the Arts September 19, 2019–January 20, 2020.

“Judy Chicago: The Birth Project From New Mexico Collections” is on view at the Harwood Museum of Art, 238 Ledoux Street, Taos, New Mexico, June 2–November 10, 2019.