On View

American Museums Ignored Him for Two Decades. Now, Julian Schnabel Is Back—and Bigger Than Ever

At least, his paintings are bigger than ever.

At least, his paintings are bigger than ever.

Sarah Cascone

Don’t call it a renaissance: ’80s art star Julian Schnabel, whose first West Coast museum exhibition in 30 years opened at the Legion of Honor at the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco late last month, wants you to know, film career notwithstanding, he’s been painting all along.

“When somebody says ‘are you still painting?’ obviously they don’t know what I’m doing,” Schnabel said during a visit to the Palazzo Chupi, the Pepto Bismol-pink Italianate mansion he designed and built in New York’s West Village. He’s garnered considerable attention for his films, such as 1996’s Basquiat and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (2007), but has tirelessly continued painting for some 40 years, deftly blurring the boundaries between abstraction and figuration.

“I like to make art,” Schnabel explained. “That’s how I mediate the world.”

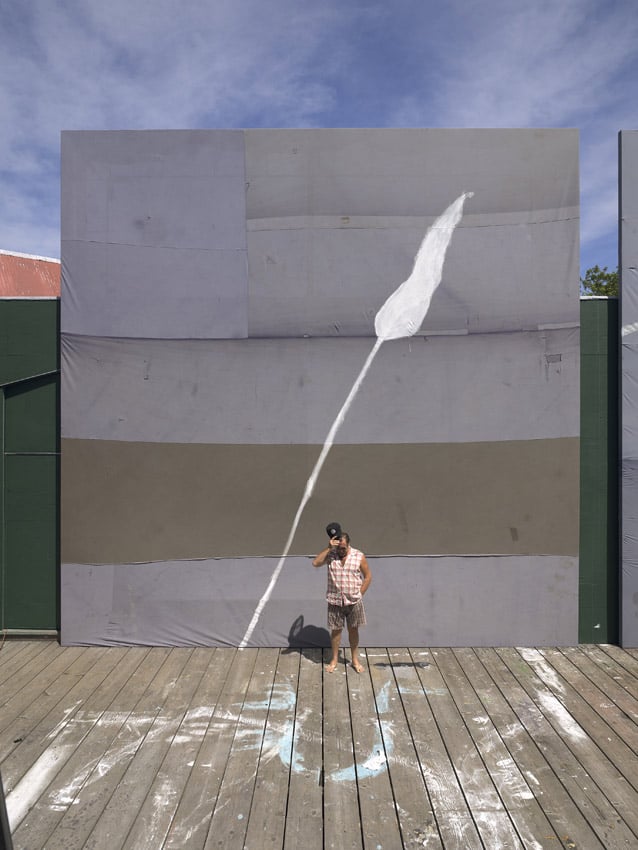

Julian Schnabel’s studio. Photo courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

The artist’s home is full of his artworks, a not-insubstantial number of which have never been shown publicly—some of the seemingly countless unseen paintings Schnabel has made over the decades. Holding back so much of his output understandably adds to the misconceptions about the recent state of his painting practice.

“I never thought about my work as a career,” said Schnabel, who is uninterested in entertaining what kind of narrative a film about his life might take, but secure in his legacy. “A generation of artists were inspired by what I did.”

Some critics agree. Schnabel’s “influence is widely visible but rarely cited,” wrote Roberta Smith in the New York Times in 2014, noting that it can be seen in the work of “all sorts of painters who emphasize chance or accident and like to work big, using unconventional materials.”

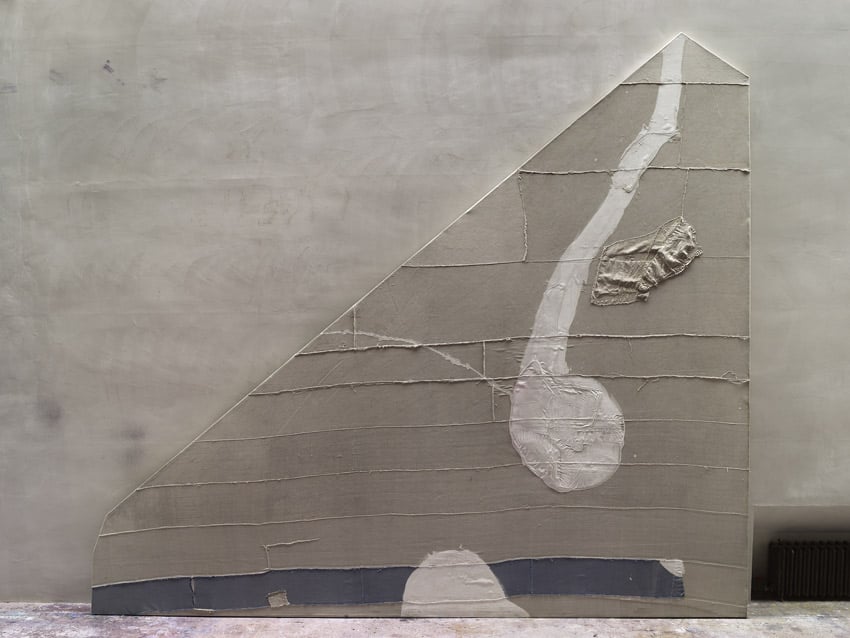

Julian Schnabel, Untitled (2017). ©Julian Schnabel Studio, photo by Tom Powel Imaging, courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

That description is spot on when it comes to his current exhibition, which includes a number of monumental works on found materials. On a trip to the Mexican jungle, Schnabel stumbled across a fruit market and was captivated by the sheets of fabric hanging over the stalls, bleached by the sun and studded with imperfections where the vendors had set down rocks to keep the cloth from blowing away.

“I didn’t paint these colors, I selected them,” said Schnabel, who adds marks of his own to the fabric, which has been stretched out between the palm trees over time into irregular shapes, and is now hung on custom-built stretchers. “A painting brings a time and place with it… all of these little nuances come with the history of the object.”

Schnabel then writes the next chapter of that history, working on his paintings outside in his Montauk studio, where they can remain exposed to the elements for months a time. “I like to work on dirty things,” he said. At the Legion of Honor, a group of the works will be displayed outside, in the museum’s open-air courtyard, modeled after the original Palais de la Légion d’Honneur in Paris—the perfect environment for these 24-foot square paintings.

“Julian Schnabel: Symbols of Actual Life” Installation view at the Legion of Honor. Photo by Moanalani Jeffrey, courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

“Julian likes the changing effect, the interpretation that architecture can give to a painting and vice versa, the marriage between the painting and the location,” wrote Max Hollein, director and CEO of the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco and the recently appointed director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in an email. “Placed around the Neoclassical-style colonnade, they are paintings as well as architectural objects. They transform the space that surrounds them and create an emotionally charged and poetic environment for the viewers.”

Inside, another series, titled “The Sky of Illimitableness,” is based on antique French Dufour wallpaper that Schnabel has digitally altered. The artist has replaced an army of soldiers in the original landscape scene with a photograph of a stuffed goat sculpture that he purchased at the old Billy’s Antiques tent on Houston Street, and then painted on top of the image with large, colorful slashes.

The paintings are shown alongside sculpture by Auguste Rodin. Since taking up his post in June 2016, Hollein has prioritized building up the institution’s contemporary art program. He launched a series of exhibitions juxtaposing historic works with that of today’s artists, a single gallery spanning the centuries. Schnabel and Hollein have known each other for some 25 years, working together on a 2004 exhibition at the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, so the artist was a natural choice for the series.

“Julian Schnabel: Symbols of Actual Life” Installation view at the Legion of Honor. Photo courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Schnabel doesn’t necessarily see himself as having been directly inspired by Rodin in any way, but has included in the show a 1982 sculpture of his own, titled Balzac, the same as one of the French artist’s most famous works. “I think artists always speak to each other beyond the grave,” Schnabel said.

He also has noticed similarities between some of shapes that recur in his work with some of Rodin’s smaller works, sculptures of details of feet and other parts of the body that appear more abstract. “I didn’t do that intentionally. It’s sort of osmosis or something,” Schnabel added.

“Julian uses all sorts of different influences, motives and elements for his paintings. They can be informed by using age-old techniques, such as painting with wax, have references to Old Masters or incorporate historical elements,” said Hollein. “It has been extremely interesting to follow his work over a long time. Julian has from the beginning of his career also been a traveler, an extremely alert and curious artist who has gone to other significant places to find inspiration and authenticity, whether through an encounter with a Renaissance master in Italy, a trip to India, Mexico, or a visit to the restaurant next door.”

Julian Schnabel, Untitled (2017). ©Julian Schnabel Studio, photo by Tom Powel Imaging, courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

In recent years, Schnabel has enjoyed renewed attention, stemming perhaps to art critic Raphael Rubinstein’s 2011 Art in America article, “The Big Picture: Reconsidering Julian Schnabel,” which decried the fact that “for more than 20 years his paintings have been passed over in silence by most critics and largely ignored by curators.” While he had significant international museum shows and regular gallery exhibitions in New York, Paris, and Berlin during this period, the films, perhaps, had eclipsed the paintings.

Indeed, US museums did not mount a single exhibition of Schnabel’s work between 1987 and 2013, when the Brant Foundation, a private institution in Greenwich, Connecticut, dedicated its spring show to the artist. The Dallas Contemporary, the NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale, the Aspen Art Museum, and now the Legion of Honor, among other US institutions, have since followed suit.

In May 2016, Schnabel closed a major chapter in his career, returning to Pace Gallery after 14 years with Gagosian, celebrating with a New York exhibition of new works from the well-known plate painting series that launched his career back in 1979.

Julian Schnabel’s studio. Photo courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

In addition to his once-again busy US exhibition schedule, Schnabel is also making his first film since 2010, a movie about Vincent van Gogh, starring Willem Dafoe. But that too involves his work on canvas—because who better than Schnabel, who has painted in many different styles throughout his career, to create a series of faux Van Goghs, self portraits where the face has been slightly tweaked to more closely resemble the movie’s lead actor?

Schnabel admits that his film career may have caused some backlash against his art. “When I first starting making movies, people didn’t want to like them,” he said. “People don’t want people to be good at more than one thing.”

Julian Schnabel, Jane Birkin (Egypt), 2017. ©Julian Schnabel Studio, photo by Tom Powel Imaging, courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Recently, much of the critical writing about the artist has embraced the idea that the artist is back in vogue. “The Great Julian Schnabel Reboot Continues,” artnet News’s editor-in-chief Andrew Goldstein proclaimed in October, citing the booth of Los Angeles’s Blum & Poe gallery at Frieze Masters in London as the latest sign of “the Julian Schnabel comeback machine.”

“It’s funny when they say you’re having a renaissance,” said Schnabel. “It’s better than saying you’re forgotten!”

“Maybe the reason that there’s the supposed renaissance,” he added, “is that this stuff never really went away.”

See more photos of the Legion of Honor exhibition below.

“Julian Schnabel: Symbols of Actual Life” Installation view at the Legion of Honor. Photo by Moanalani Jeffrey, courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Julian Schnabel, Untitled (2017). ©Julian Schnabel Studio, photo by Tom Powel Imaging, courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Julian Schnabel, Untitled (2017). ©Julian Schnabel Studio, photo by Tom Powel Imaging, courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

“Julian Schnabel: Symbols of Actual Life” Installation view at the Legion of Honor. Photo courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

“Julian Schnabel: Symbols of Actual Life” Installation view at the Legion of Honor. Photo by Moanalani Jeffrey, courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

This article originally appeared in ArtMag by Deutsche Bank under the title “‘Julian Schnabel: Symbols of Actual Life’ at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco.”

“Julian Schnabel: Symbols of Actual Life” is on view at the Legion of Honor, Lincoln Park,100 34th Avenue, San Francisco, April 21–August 5, 2018.

“Julian Schnabel: The re-use of 2017 by 2018. The re-use of Christmas, birthdays. The re-use of a joke. The re-use of air and water” is on view at Pace, 6 Burlington Gardens, London W1S 3ET, May 17–June 22, 2018.