Sexuality and the nude in the work of Gustav Klimt (1862–1918), Egon Schiele (1890–1918), and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) are taking center stage at the Metropolitan Museum of Art this summer. The Met Breuer is dedicating an exhibition to the collection of one Scofield Thayer (1889–1982), a pioneering magazine publisher with a voracious eye for erotic art.

“Thayer was a bundle of contradictions—a millionaire who voted socialist, a romantic with a penchant for prostitutes, and a collector who professed to ‘detest’ Modern art and yet who arguably did more than anyone to bring Modernism to the United States,” said James Dempsey, an instructor at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute and author of the 2014 biography The Tortured Life of Scofield Thayer, in an email to artnet News.

Thayer lived in Vienna between 1921 and 1923, where he was treated by Sigmund Freud. There, he was also exposed to artists utterly unfamiliar to American art collectors, purchasing a large group of Schiele and Klimt’s watercolors and drawings. In just a few short years, the eccentric amassed a world-class collection of some 600 representational works by American, Austrian, French, German, Norwegian, Russian, and Spanish artists.

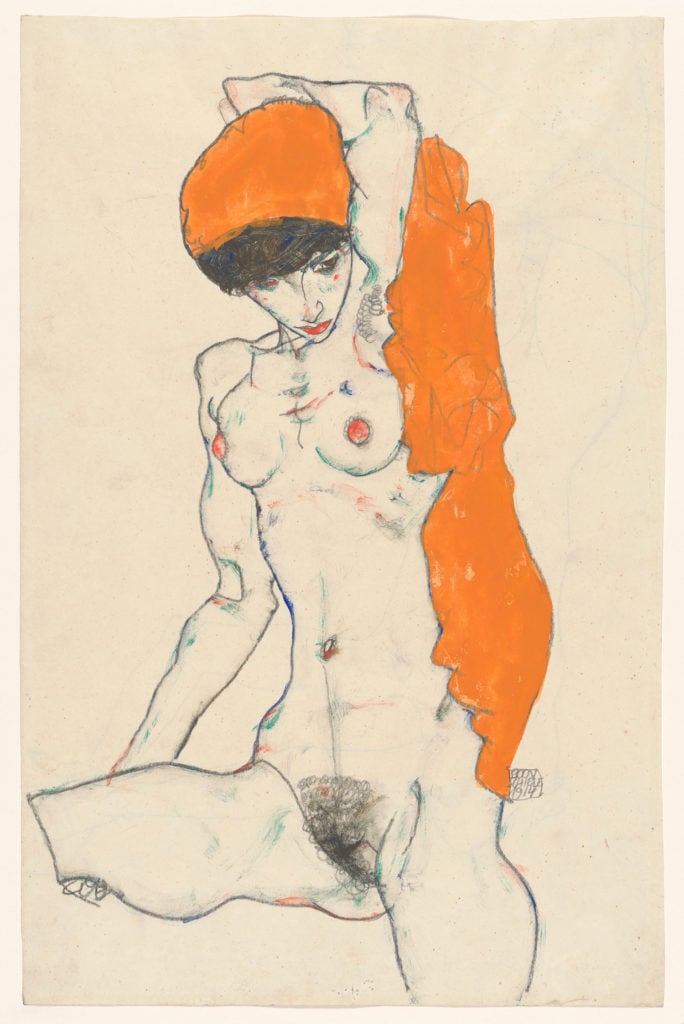

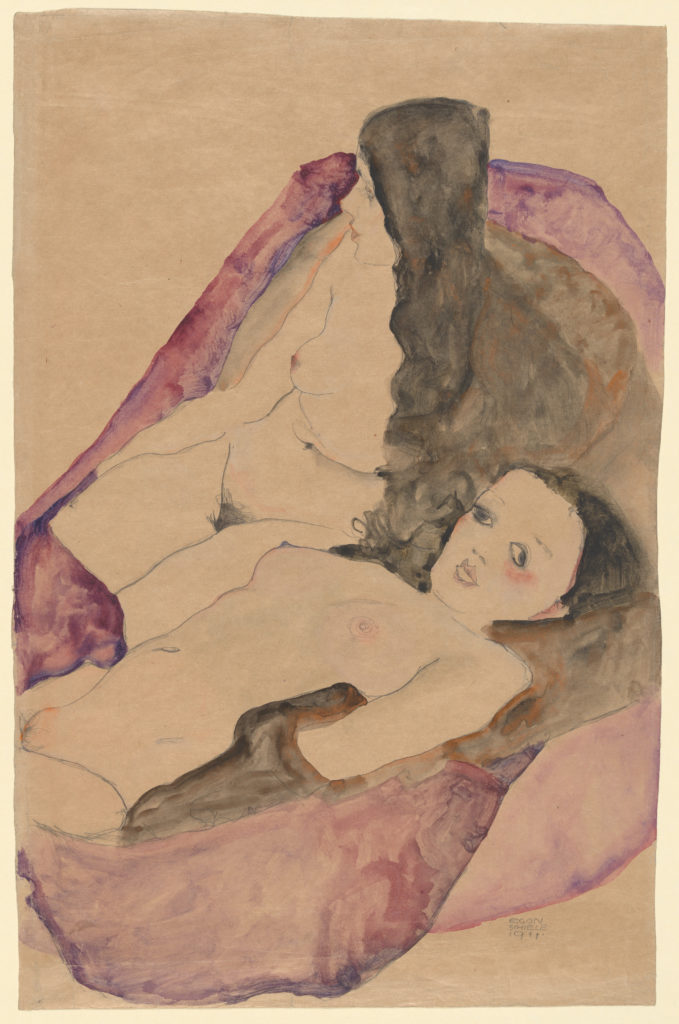

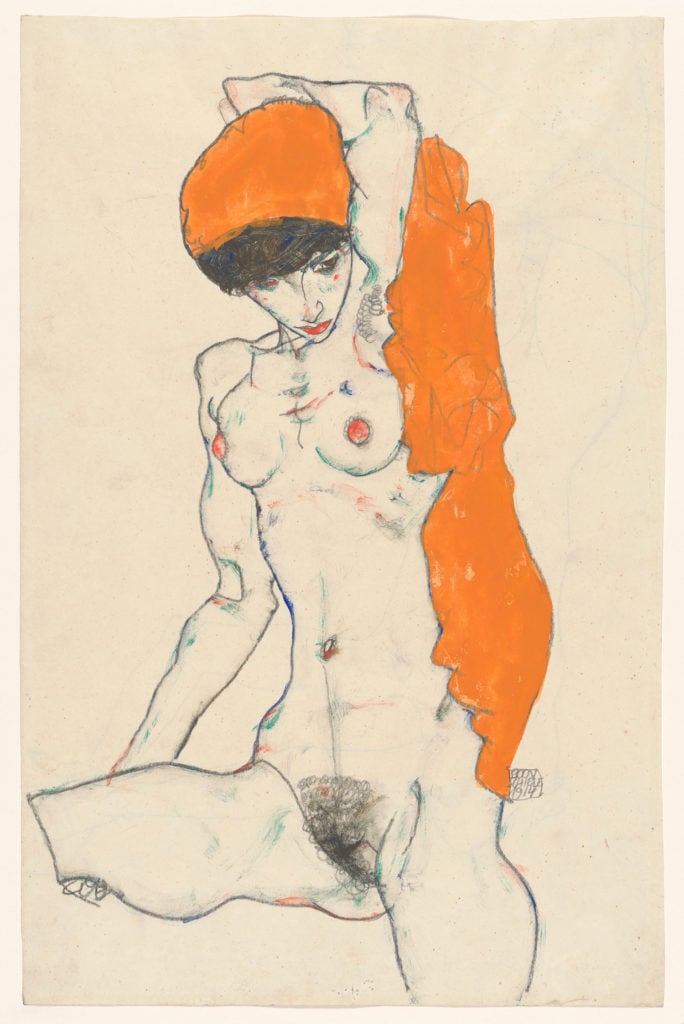

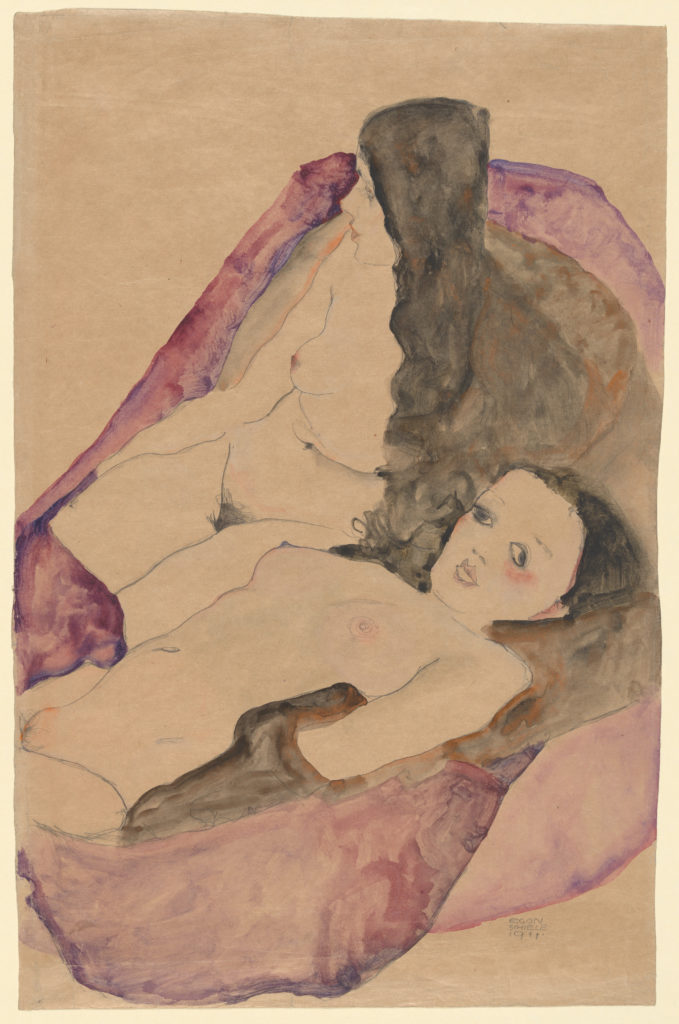

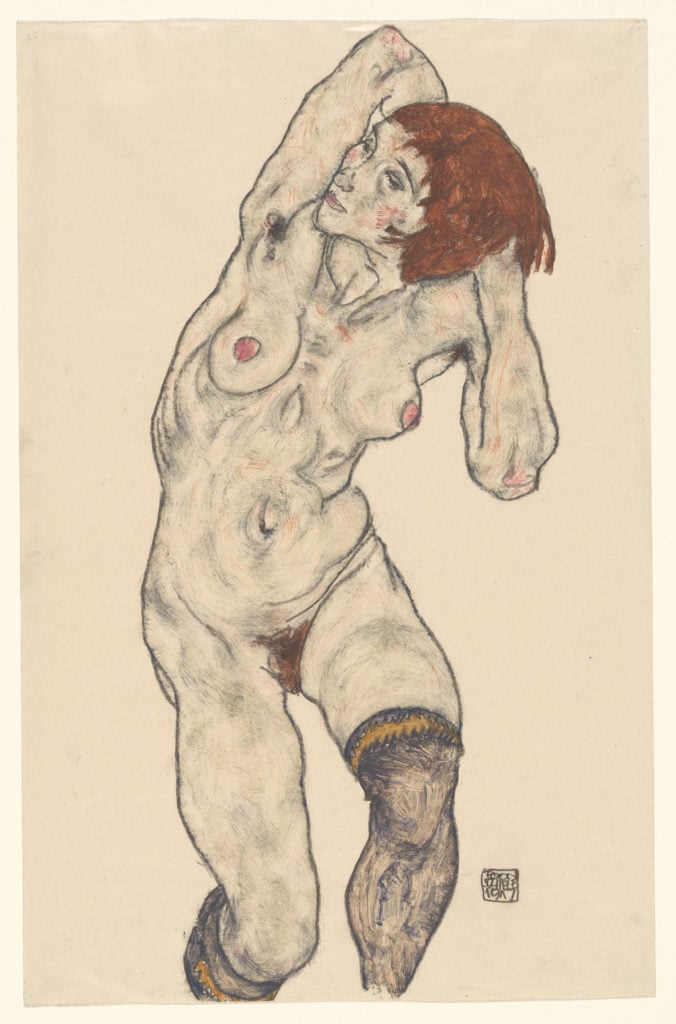

Egon Schiele, Standing Nude with Orange Drapery (1914). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, bequest of Scofield Thayer, 1982.

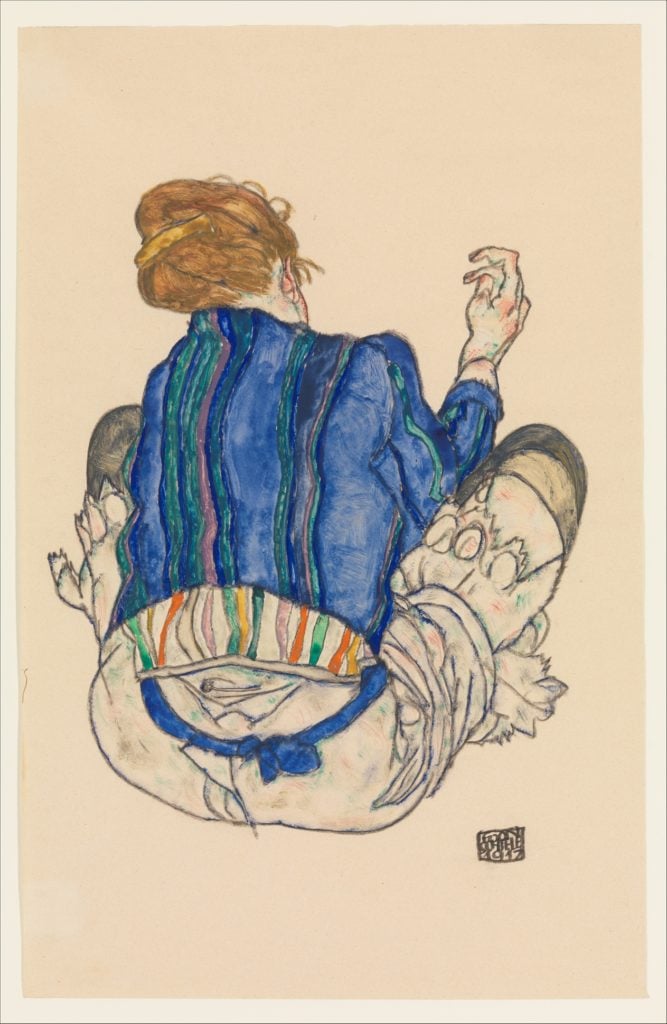

A poet, Thayer collected with an eye toward illustrating his art and literary magazine, the Dial, which paired the writings of the likes of E.E. Cummings, T.S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf, Ezra Pound, and D.H. Lawrence with reproductions of Modern art—which explains the preponderance in his holdings of line drawings that could be reproduced in black and white. Begun as a Transcendentalist periodical in 1840 before being reborn at Thayer’s hands as a Modernist publication in 1920, the magazine was a leading avant-garde journal until its folding in 1929.

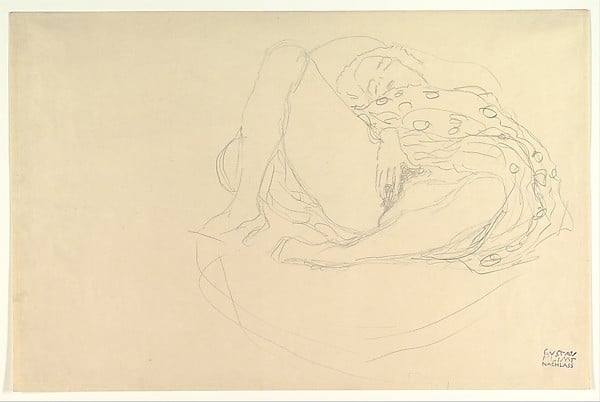

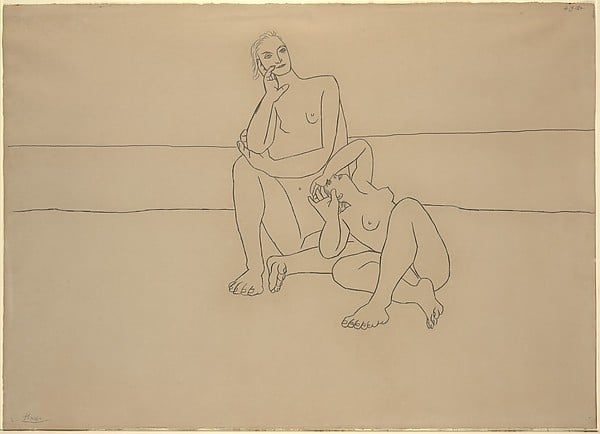

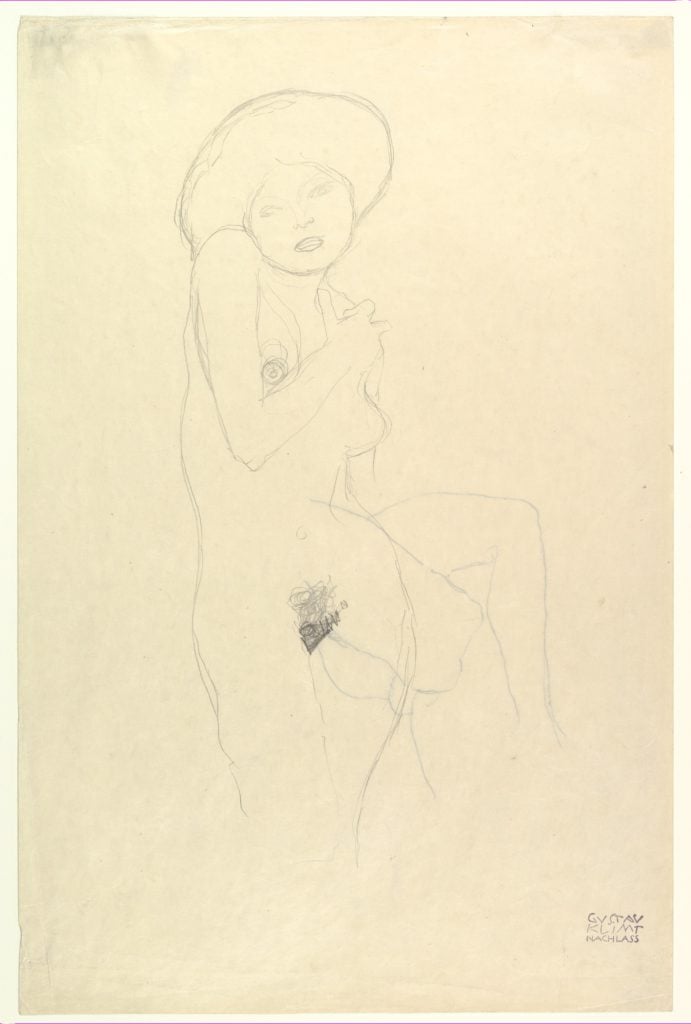

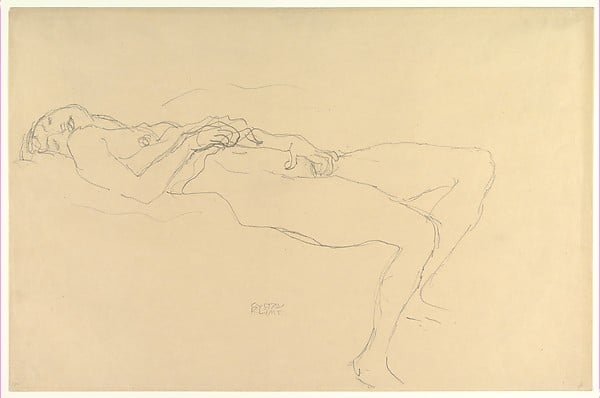

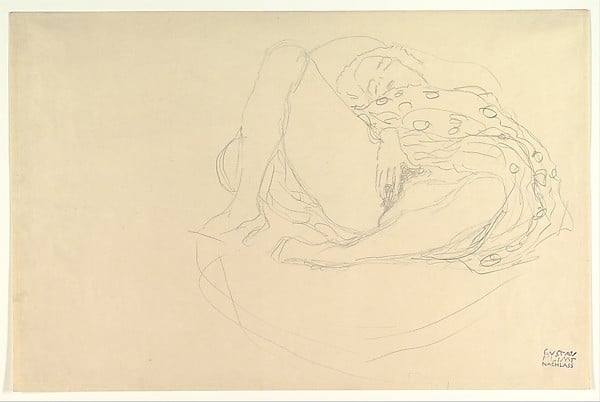

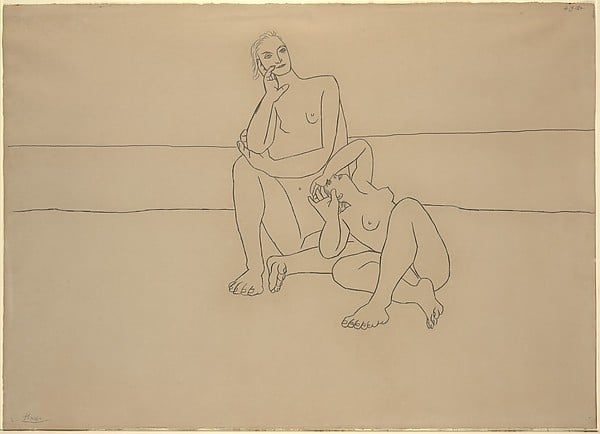

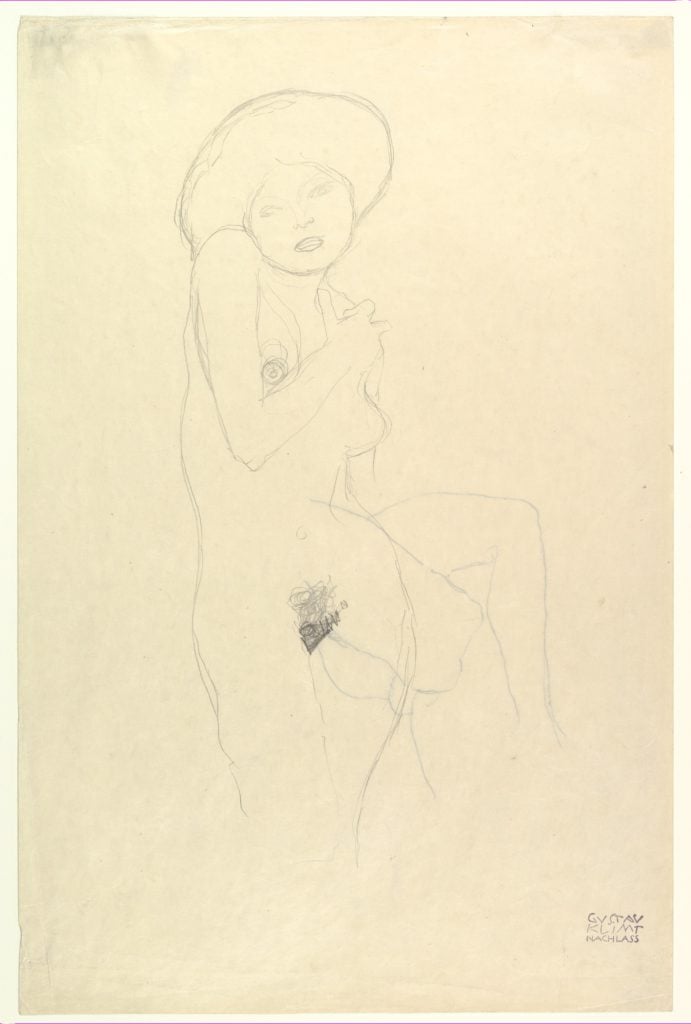

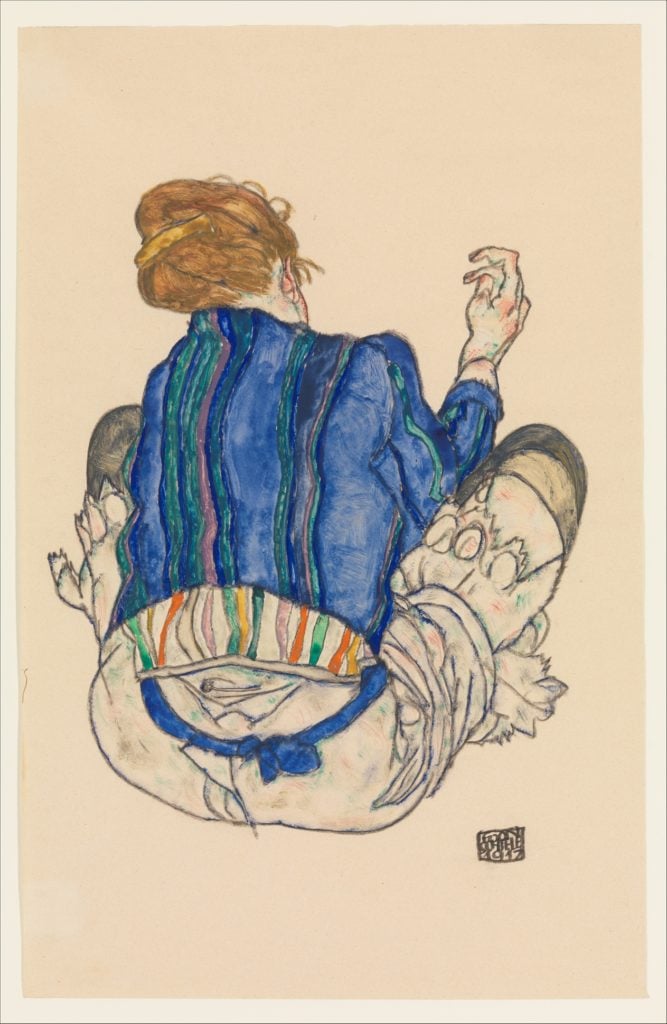

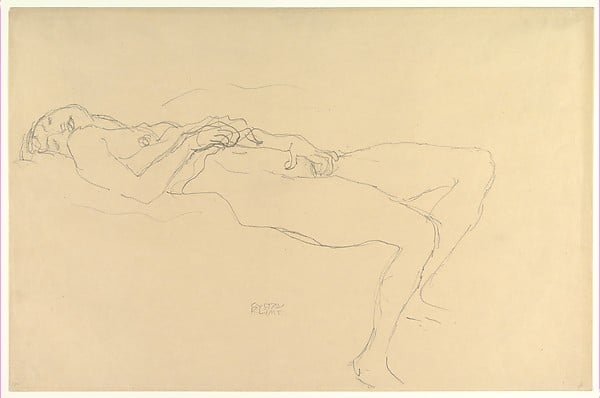

But while Thayer certainly bought art for the pages of the Dial, he also bought other art “for my private pleasure,” as he admitted in a letter to his mother. Klimt, with his affinity for the female nude and occasional forays into masturbation and lesbianism, was a logical choice. His pupil, Schiele, made even more erotic work. Picasso, too, shared their love for the naked female form.

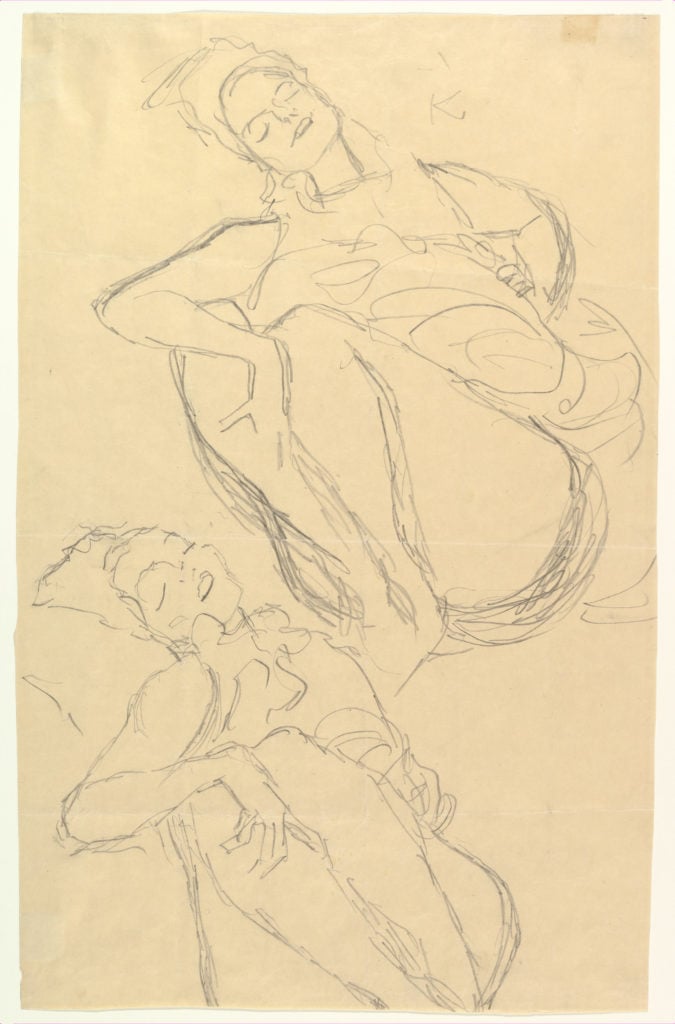

Gustav Klimt, Reclining Nude With Drapery (c. 1913), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“Most of the works in the exhibition never appeared in the Dial, probably because of the erotic nature of many of them, which even a progressive magazine such as the Dial would hesitate to print at the time, fearing obscenity charges,” noted Dempsey, who co-authored the exhibition catalogue along with Met Modern art curator Sabine Rewald. Dempsey is also working on a documentary about Thayer.

Thayer suffered a mental breakdown in 1926 and left Europe. (Dempsey believes he likely suffered from paranoid schizophrenia.) Upon his return to the States, Thayer showed his collection to great acclaim at the Montross Gallery in New York before settling into a reclusive existence until his death in 1982.

For the intervening 50 years, the collection was stored free of charge in his hometown, at the Worcester Art Museum, where Thayer was generally expected to bequeath the works. Instead, he left most of his collection to the Met. “This was heartbreaking for many in Worcester and left a great hole in Worcester museum’s holdings,” Dempsey said.

Pablo Picasso, Two Bathers Seated by the Shore (1920), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. © 2018 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The new exhibition is showing these erotic works together for the first time. “The Scofield Thayer collection spans some four centuries and nearly 600 works. Its great diversity and unevenness precluded a publication or an exhibition,” Rewald told artnet News in an email. “Since over 90 percent of the collection are works on paper, these works cannot be on permanent view due to the delicate nature of the material.”

It also doesn’t hurt that 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of Klimt and Schiele’s deaths, currently being celebrated at institutions around the world. Clearly, the time was right to bring Thayer’s collection back into the spotlight. (A smaller exhibition, “Nudes: A Selection from the Bequest of Scofield Thayer,” appeared at the Met in 1993, also curated by Rewald.)

The timing of exhibition is in some ways challenging, however: In the wake of the #MeToo movement, Schiele and Picasso have both come under fire for their treatment of women. Picasso’s biographer recounted incidents of violence at the artist’s hands against wives and lovers, and Schiele was arrested for allegedly kidnapping and raping a 14-year-old girl. There have been calls by some—including a nearly-nude protest by artist Emma Sulkowicz at New York museums—for institutions to mention clearly when a featured artist has been accused of mistreating women. (The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston did just that for their recent Klimt/Schiele show.)

The Met does not address this issue with Picasso but acknowledges the Schiele allegations, defending the artist. In the exhibition catalogue, Rewald wrote that “the accusations against Schiele… are still repeated today in a sensationalist and distorted fashion,” and “the experience was shattering to the artist.”

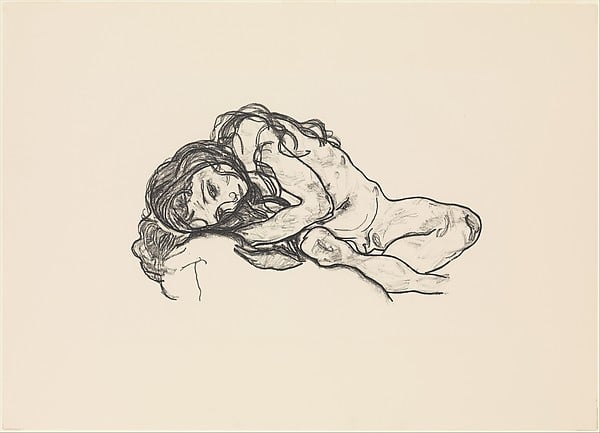

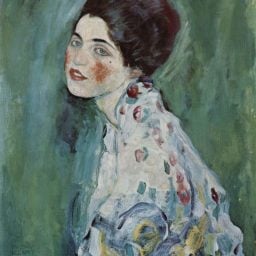

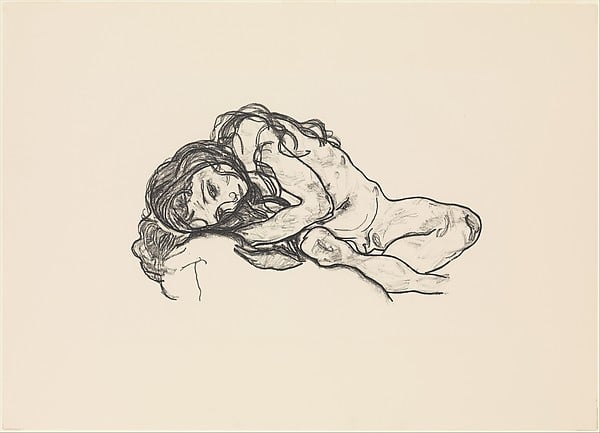

Egon Schiele, Girl (1918), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

According to the exhibition wall text, “the evidence suggests that a fourteen-year-old girl had run away from home and sought refuge with the couple. Before she returned unharmed a day later, her father had filed charges of kidnapping and statutory rape with the police, who then raided the artist’s studio and confiscated a group of erotic artworks.” (Schiele was found innocent of the more serious charges, but guilty of exposing minors to obscene material, as his nude sketches were in the studio, where local children often came to play.)

Rewald, who based research on the writings of Schiele scholar Jane Kallir, notes that the incident led the artist to stop employing underage models. Even so, there are three 1918 works of a 10-year-old girl, which the catalogue describes as “chaste and vulnerable,” with one drawing revealing the subject’s pubic area.

“There was never a question not to include the drawings of naked young girls, as we know that they are the models’ daughters, brought with them to the artist’s studio,” Rewald told artnet News. “To me, as an art historian, the works can only be contextualized in Vienna at the time Klimt and Schiele worked there. It is difficult to properly contextualize these works in contemporary American society, but that is what our visitors can do if they so choose.”

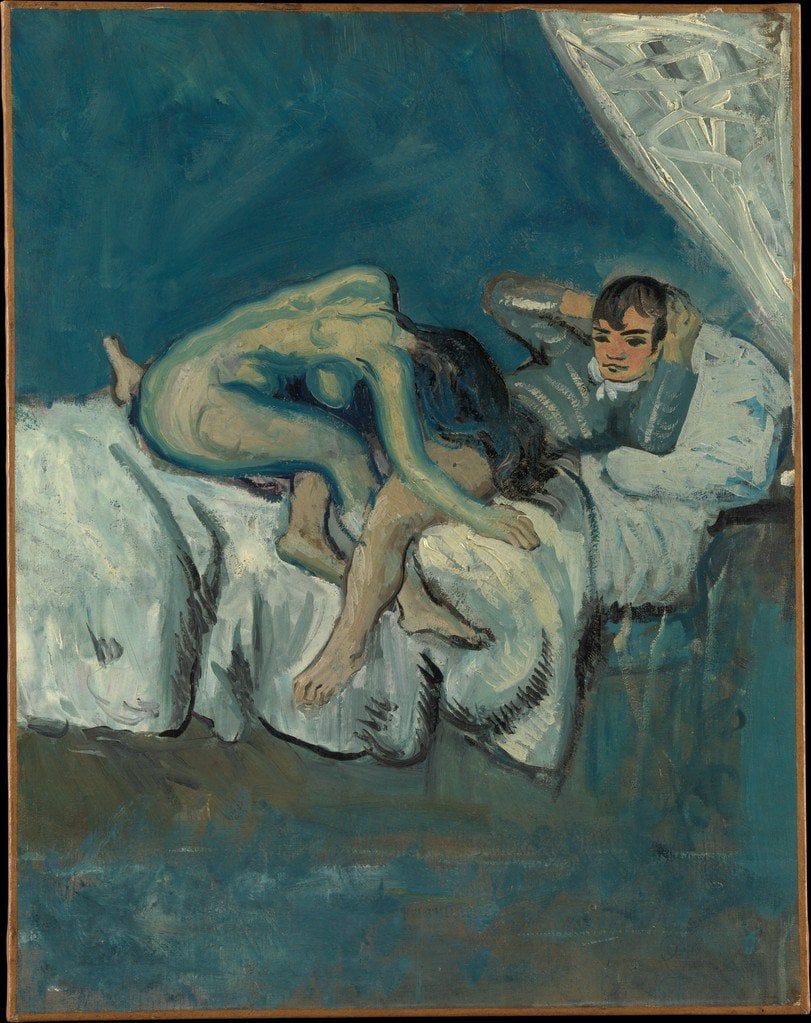

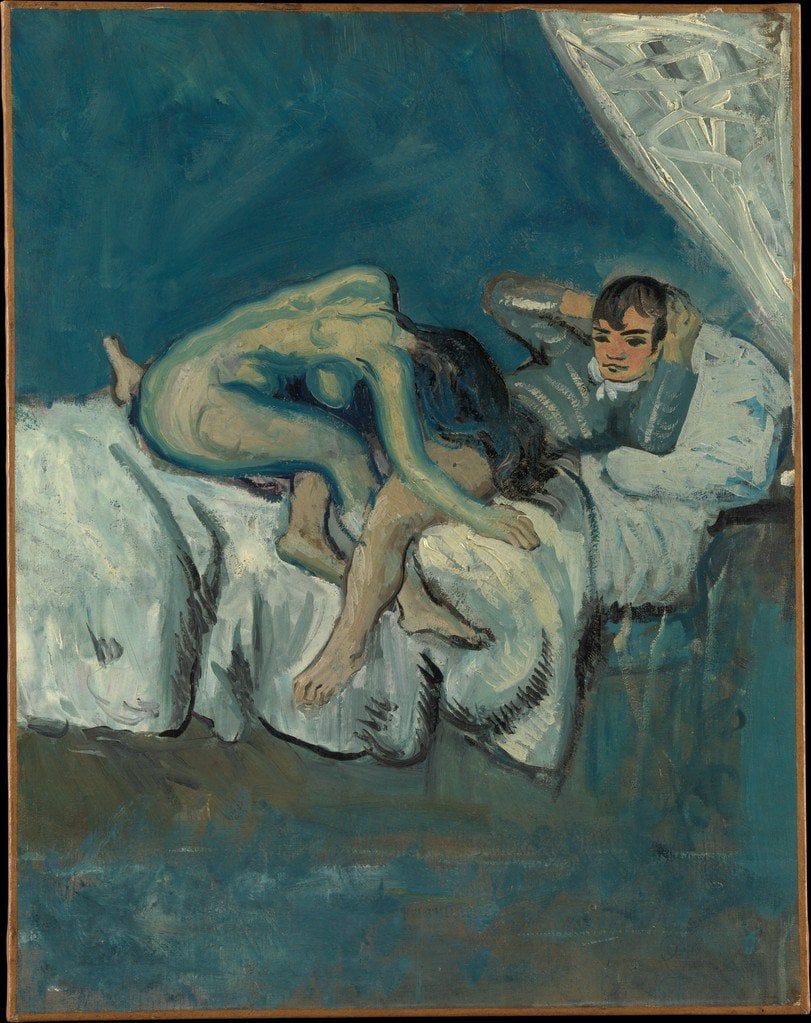

The Schiele drawings are far from the most risqué in the show. That honor goes to Picasso’s Erotic Scene (La Douceur), an explicitly sexual early canvas in which a naked woman buries her head a young man’s lap. (Picasso later denied making the work, insisting “it was a joke by friends.”) Thayer picked up the racy 1903 oil painting in 1923; it had been sold at auction earlier that year, hidden inside a hinged panel on the back of a Cubist still life.

Pablo Picasso, Erotic Scene (La Douceur), 1903, donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

“After [Thayer] was declared insane, it was put into a trunk with a bunch of other erotic stuff and stored on Pleasant Street in Worcester, in a warehouse, for over 60 years, until he died,” Dempsey told the Worcester Telegram. “The picture is quite famous; experts knew it existed but didn’t know where it was.”

Scholars acknowledge the piece as part of Picasso’s oeuvre despite his disavowal. In the exhibition catalogue, Rewald wrote that it “may recapture an episode of the adolescent artist’s sexual initiation in a Barcelona brothel.”

The Met didn’t show the rediscovered painting for nearly 30 years, until they displayed the entirety of their Picasso holdings in 2010—“not because of its subject matter or because of questions of its authenticity, but because it’s not very good,” Gary Tinterow, then the Met’s curator of 19th-century, Modern and contemporary art, told the New York Times at the time.

Now, viewers will once again have the chance to judge for themselves with this wide selection of nude drawings. See more works from the exhibition below.

Egon Schiele, Observed in a Dream (1911), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

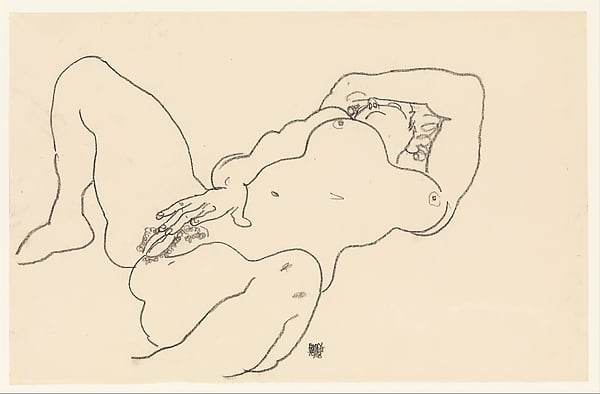

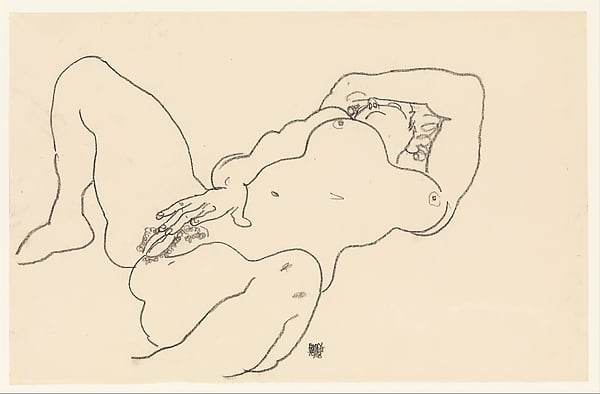

Egon Schiele, Reclining Nude (1918), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

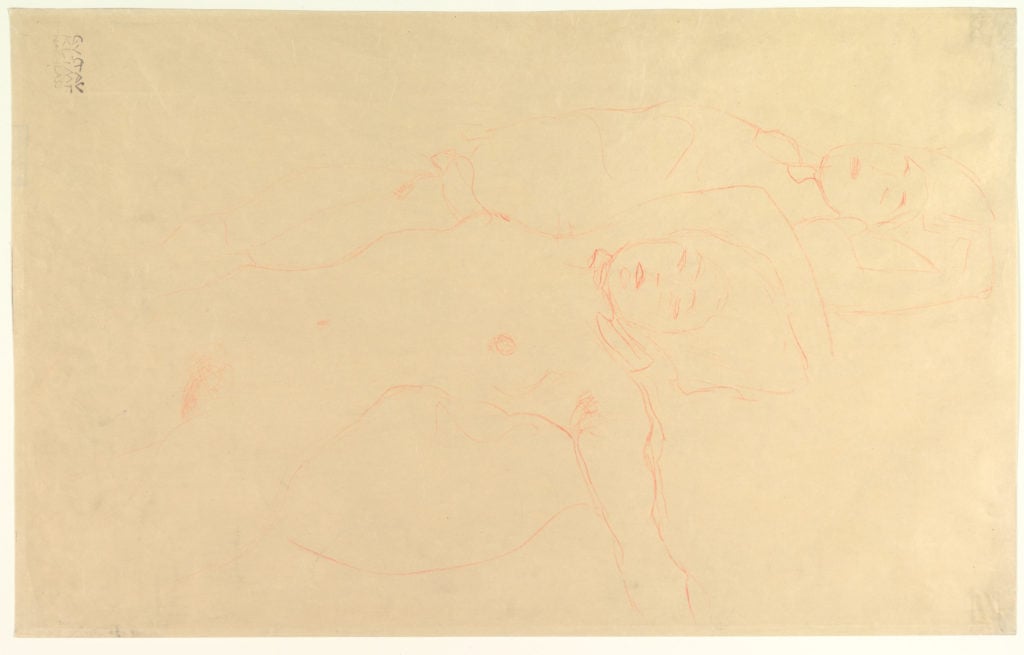

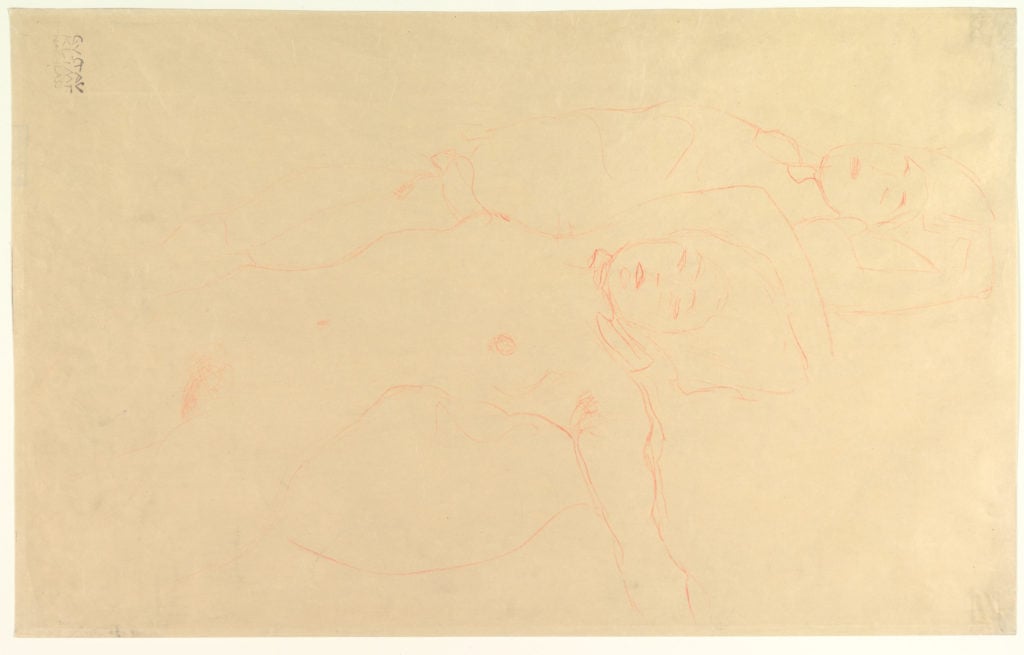

Gustav Klimt, Two Reclining Nudes (1905–06), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

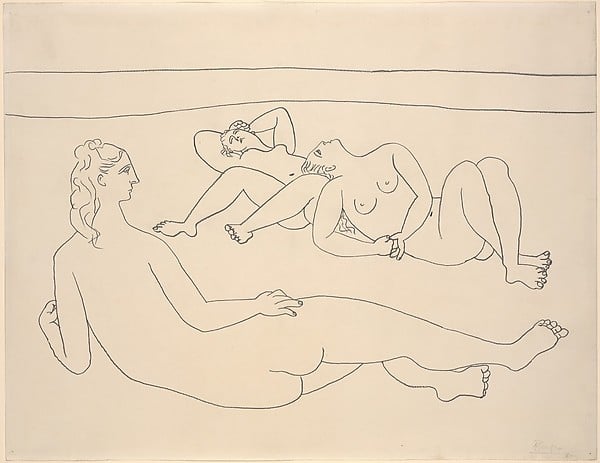

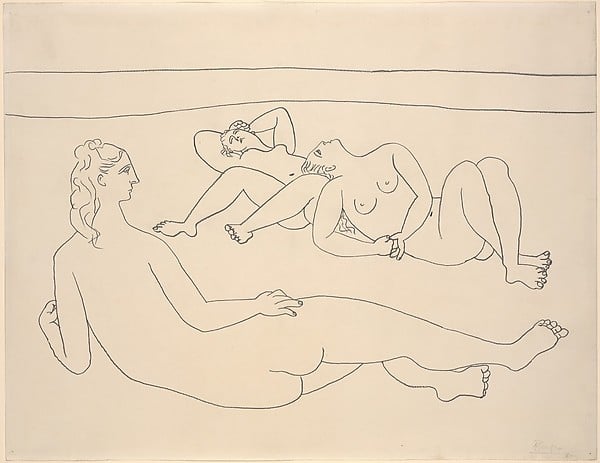

Pablo Picasso, Three Bathers Reclining by the Shore (1920), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. © 2018 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Egon Schiele, Two Reclining Nudes (1911), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Gustav Klimt, Standing Nude (1900–07), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Egon Schiele, Seated Woman, Back View (1917), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Gustav Klimt, Reclining Nude (c. 1913), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

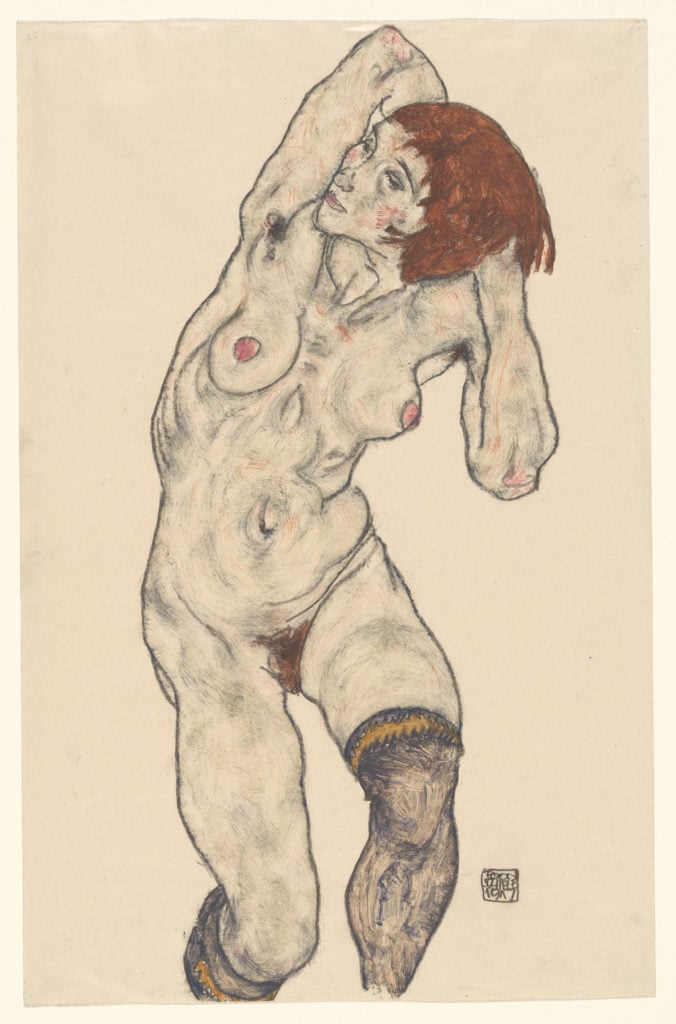

Egon Schiele, Standing Nude in Black Stockings (1917), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

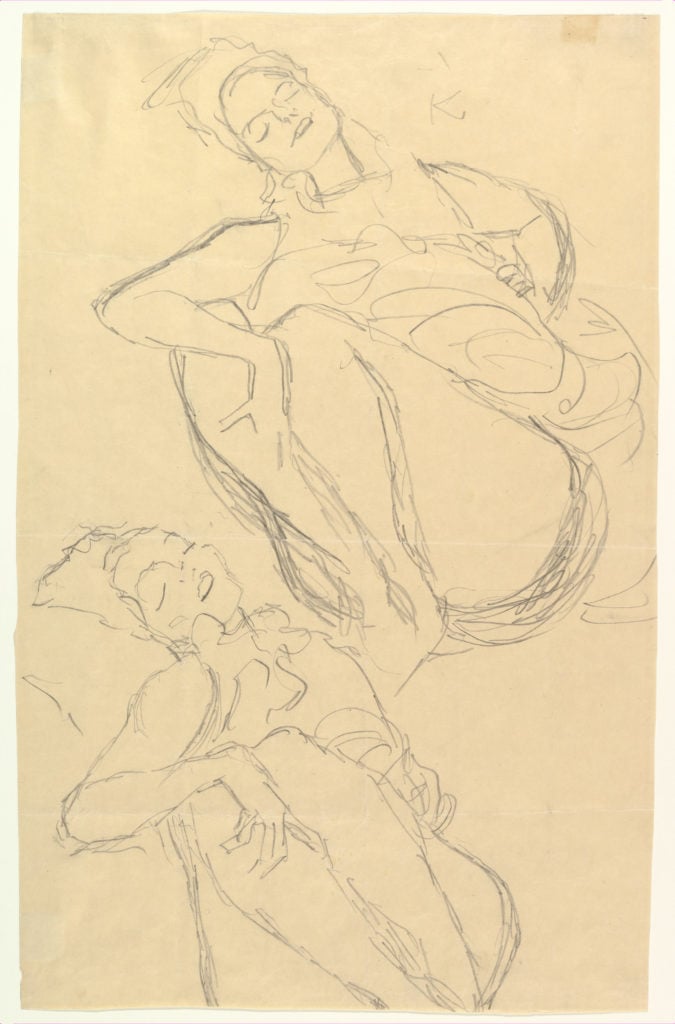

Gustav Klimt, Two Studies for a Crouching Woman, (1914–15), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“Obsession: Nudes by Klimt, Schiele, and Picasso from the Scofield Thayer Collection” is on view at the Met Breuer, 945 Madison Avenue at East 75th Street, New York, July 3–October 7, 2018.