Reviews

Liverpool Biennial 2016 Hits the Spot Between Eccentric and Politically Engaged

Freewheeling performances and sophisticated moving image works lead the pack.

Freewheeling performances and sophisticated moving image works lead the pack.

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

The ninth edition of the Liverpool Biennial, the UK’s largest contemporary art festival, opened on Saturday across the city’s foremost museums and galleries, public spaces, and a few landmark venues rarely open to the public.

The show gathers works by 44 artists and has been put together by a troop of 11 curators (or “Curatorial Faculty”), which includes the biennial’s director Sally Tallant; Francesco Manacorda, artistic director of Tate Liverpool; Raimundas Malasauskas; Rosie Cooper; Francesca Bertolotti-Bailey, head of production and international projects of the biennial; Ying Tan, curator of the Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art; and Steven Cairns, associate curator of artists film and moving image at London’s ICA.

Given the high number of curators per square meter involved, it comes as no surprise that the biennial’s thematic conceit feels so intensely “curatorial”—and by that, I mean a device so cumbersome that it’s mostly useful to the show’s curators alone, while limiting the public’s readings of the artists’ works and overall experience of the event.

Liverpool Biennial 2016 Curators in Chinatown. Photo Shirlaine Forrest/Getty Images on behalf Liverpool Biennial.

In the exhibition’s guide we are told that the biennial “explores fictions, stories, and histories, taking the viewers on a series of voyages through time and space, drawing on Liverpool’s past, present, and future.”

In order to structure these travels, the curators have divided the show in six “episodes:” Ancient Greece, Chinatown, Children’s Episode, Software, Monuments from the Future, and Flashback. Many artists participate in various episodes, and some venues host several of those episodes (excuse the tongue twister), so which work is exactly in what episode and for what reason is never entirely clear.

Still, once one decides to step over that pesky problem, the biennial offers plenty of superb art to be enjoyed.

Of the main biennial venues, the most successful group show is the one at Cains Brewery, a stunning Victorian red brick building that closed to the public in 2013 and is awaiting redevelopment.

In the brewery’s canning hall, Celine Condorelli’s beautiful sculpture Portals: Chinatown (2016) welcomes visitors to a large number of installations and videos that coexist with the decaying industrial interior. It’s a busy setup that repays long, detailed inspection so the individuality of the artworks can slowly emerge.

Organized around a large structure by Andreas Angelidakis titled Collider, are works by Marvin Gaye Chetwynd, Ian Cheng, Betty Woodman, Lara Favaretto, and Rita McBride, among others.

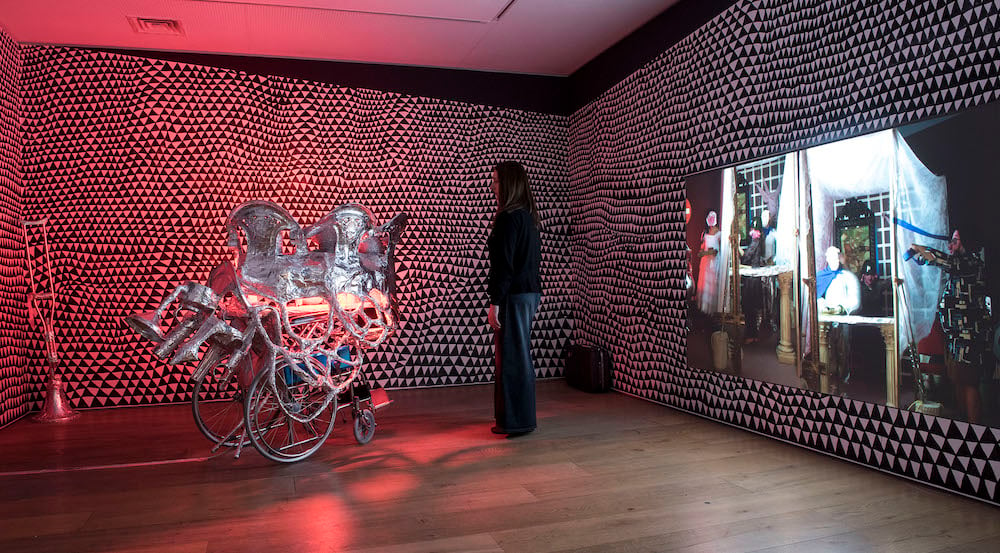

Installation view of works by Rasmin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh, and Hesam Rahmanian at Open Eye Gallery, Liverpool Biennial 2016. Photo Joel Fildes.

The highlight here (and of the biennial at large) are the pieces by Rasmin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh, and Hesam Rahmanian, a collaborative trio of artists from Iran who work across performance, installation, painting, and sculpture.

The art works presented at the biennial have all been made at the Dubai house where the three artists—two brothers and their childhood friend—live in exile; a shared villa that has become a stage or film set of sorts for their gender bending works and exercises in curating and collecting, which they like to recreate as part of their exhibitions.

Their sprawling collaborative practice deals with a number of issues, including the notion of the human body as an empty shell, or container to be inhabited, which manifests itself in video-performances in which the artists disguise themselves as cartoonish characters, dressed in highly imaginative, home-made costumes, bringing to mind children’s make-believe games.

The idea of smuggling as a political act is also key for the trio, and in fact, their displays are dotted with artworks from their own art collection (including pieces by Rosemarie Trockel, Kiki Smith, Mona Hatoum, Helen Chadwick, and Robert Mapplethorpe), which they smuggled from Dubai to Liverpool in a shipping container, disguising certain artworks beneath cheaper everyday items, thus also challenging the way the value and circulation of art is regulated by bureaucracy.

Marvin Gaye Chetwynd, Dogsy Ma Bone (2016), Liverpool Biennial 2016. Photo Mark McNulty, courtesy the artist, Liverpool Biennial and Sadie Coles HQ.

Nearby, and also exuding a similarly child-like élan, was the displayed documentation of and props from Chetwynd’s newest performance, Dogsy Ma Bone (2016). Made in collaboration with almost 80 local children and teenagers, and inspired by both Betty Boop and Bertolt Brecht, this epic dance hall piece was also performed live on Saturday for a few guests.

At the back of the brewery, two large installations by Audrey Cottin brought the tone down to a more meditative frequency. The large floor sculpture Lift-me (2011), made with tubes, ropes, and tennis balls—a sort of contemporary take on Arte Povera—almost fused itself with existing building features in a rather magical, almost monastic way.

Audrey Cottin, Lift-me (2011) at Cains Brewery, Liverpool Biennial 2016. Photo Lorena Muñoz-Alonso.

But in order to reach them, one had to dodge the journalists blindly stumbling across the space as they had a go at Ian Cheng’s Emissary Forks For You (2016), an interactive piece for tablets starring Shiba Emissary, Cheng’s recurrent virtual super dog. In it, users have to (literally) follow the dog across the exhibition space, and when reached, they are rewarded with a “well done” of sorts (the human equivalent of “good boy/girl”?). It is a piece in which humans become pets and pets become masters, which might question the status quo of nature as it stands. Or, alternatively, just a bit of lighthearted fun.

Nearby, Mark Leckey’s Dream English Kid (2015) was being screened at the Blade Factory—the replacement venue after the original Saw Mill was consumed by fire a week before the opening. First shown at London’s Cabinet gallery last year, this new film is a sort of “Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore-redux,” invoking Leckey’s seminal 1999 film, which explored British popular culture through the angle of dance and music. His new film is a beguiling piece, for sure, but it feels a little hackneyed. Interestingly, I found the film bore the influence of both Elizabeth Price and Ed Atkins, two artists who have been seen as continuing Leckey’s artistic language. Oh, the eternal return.

Statue of Apollo Sauroktonos, 1st century AD on display in Ancient Greece at Tate Liverpool as part of the 9th of Liverpool Biennial. Photo ©Tate Liverpool, Roger Sinek.

Over at Tate Liverpool, another of the main venues, a group show featuring artists including Koenraad Dedobbeleer, Alisa Baremboym, Woodman, Condorelli, Mariana Castillo Deball, Jason Dodge, and Jumana Manna, among others, tackled the episode of Ancient Greece. This was done through a mixed display of works by these contemporary artists with sculptures, vases, busts, and reliefs from the National Museums Liverpool’s antiquities collections.

The installation of Manna, drawing parallels between Athens and Jerusalem, and the textural explorations of Baremboym’s sculptures reigned supreme in a show that seemed to be blindly following the art fair trend du jour of staging cross-historical displays (see Frieze Masters, or Cahn and Jocelyn Wolff’s shared booth at Independent Brussels this year), the whims of the art market evidently entering the museum.

At The Oratory, a small Victorian chapel full of neoclassical busts and sculptures just outside the Liverpool Cathedral, the Beirut-based artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan is presenting Rubber Coat Steel (2016). The film is a continuation of his riveting ongoing research into audio forensics and the violence inflicted by sound, either in warfare or by use of voice and accents as telltale signs at border controls as a way to curtail immigration.

Through subtitles and images depicting the sound waves generated by different weapons, Rubber Coat Steel narrates the involvement of Hamdan, who’s also a forensic audio analyst, in an investigation into the deaths of Nadeem Siam Nawara and Mohammad Mahmoud Odeh Abu Daher in the West Bank in 2014. His research proved that the teenage boys had been shot and killed by real bullets, and not rubber ones, as the Israeli Defense Forces claimed.

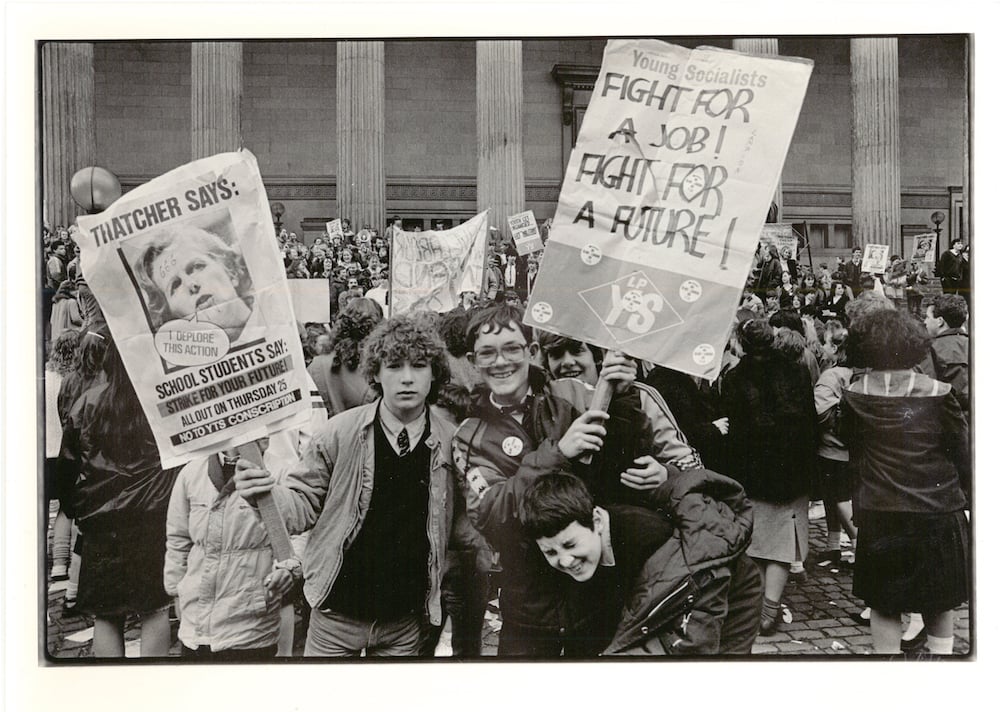

Dave Sinclair, Youth Training Scheme Protest, Liverpool, 25 April 1985. Image courtesy of Dave Sinclair.

Meanwhile, at Open Eye Gallery (alongside further works by Rasmin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh, and Hesam Rahmanian) a film by Koki Tanaka revisits the march that took place in Liverpool on April 25, 1985 to protest against the Conservative Government’s Youth Training Scheme, which was seen as a way of providing cheap labor with no guarantee of a job.

Photographed by David Sinclair and published in his book Liverpool in the 1980s, the images of the march were the starting point for Tanaka’s project, who saw in them a potent combination of hope and anger. In June this year the Japanese artist invited original participants to walk again and share their memories with the younger generation, discussing with them how the 1985 protest relates to the issues that British youths face today.

In a summer in which Brexit has plunged the economy and political landscape of the country into disarray, it feels like a very pertinent question indeed. With demonstrations, marches, and petitions against Brexit taking place, and with the female Conservative Theresa May just appointed as Prime Minister, it seems that we are not too far from the 1985 of Margaret Thatcher.

Lucy Beech, film still from Pharmakon (2016) at FACT, Liverpool Biennial 2016. Photo Lorena Muñoz-Alonso.

But if there was a film that truly stole the show it was Lucy Beech’s Pharmakon (2016) at FACT. The film tells the story of a female security guard who’s increasingly drawn into a world of bodily self-examination, hypochondria, and anxiety, and explores how these fears can be simultaneously alleviated and monetized by support groups and online businesses.

The theme might bring to mind the work of Shana Moulton, but while Moulton’s films and performances are highly humorous, verging almost on camp parody (perhaps a self-defense mechanism), Beech’s approach carries a certain gravitas, is serious and earnest, and displays a keen cinematic gaze.

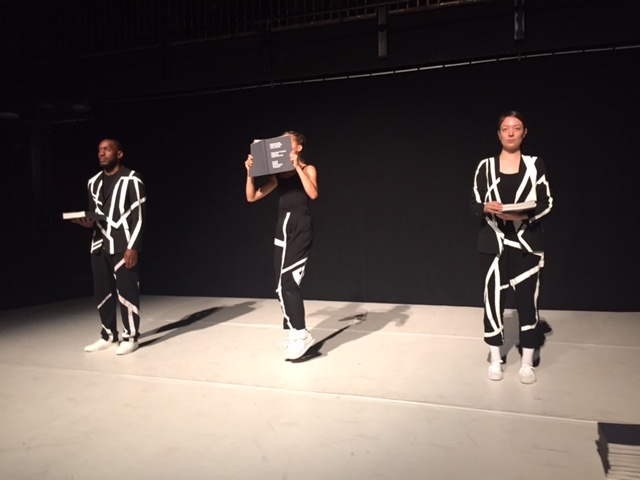

Performance is a strong element in the biennial’s program, and it reached its apex with the superb performance of Michael Portnoy’s Relational Stalinism: The Musical (2016), which was performed during the preview and opening days. Although not a new piece for the biennial—it was originally commissioned in exhibition format for the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam earlier this year—it’s most definitely one of its highlights.

Michael Portnoy, Relational Stalinism: The Musical (2016), performed at the Black-E theater as part of the Liverpool Biennial 2016. Photo Lorena Muñoz-Alonso.

The piece is formed by nine acts featuring a group of seven phenomenal performers who act, dance, and sing, to hysterical results most of the time. The content is a witty take down of the “radical chic” criticality that has conquered museums and kunstvereins all over the world, particularly where it concerns the use of concepts such as performativity and immaterial labor as weapons to be brandished by bien pensant curators, critics, and artists.

During the opening act, titled Mental Footnotes, for example, three actors pass books between each other while Portnoy reads their titles out loud, which include: “Duration for dummies,” “Curators say: dance good, theater bad,” “Post-dance: using your laptop on stage with grace,” “Overcoming your fear of materials and learning to sculpt again: a dancer’s journey.”

Another act, meanwhile, involves a performer assuming the role of An(al) Lee(k), a discarded Japanese robot too malfunctioning to perform in Tino Sehgal’s Ann Lee piece, which itself borrowed the Annlee character, first appropriated in turn by Pierre Huyghe and Phillipe Parreno back in 1999.

Portnoy’s might craft cheeky insider’s jokes for art geeks, but if you are one, it works, and it’s hilarious. It’s a performance with something to say and with a great way of saying it. And it’s a success to which the strength of each of the performers no doubt contributes to.

Betty Woodman posing with her public art piece Liverpool Fountain (2016), Liverpool Biennial 2016. Photo Joel Fildes.

The piece struck me as symbolic of the biennial at large, which displays a fresh and rare balance between the wacky and the politically engaged. The heavily curated structure might have been a slight faux-pas, but it’s more than compensated for by the quality of many of the works they chose. I felt the curators prioritized works that were either more freewheeling, funnier, or less stiflingly self-conscious than much “biennial art,” and that in itself is definitely cause for celebration.

The Liverpool Biennial is taking place in venues across the city, from July 9-October 16, 2016.