Reviews

3 Artists Shaking Up the Way We See the City in the Hammer’s Bold New ‘Made in LA’ Biennial

The show puts the spotlight on artists doing imaginative and heartfelt work.

The show puts the spotlight on artists doing imaginative and heartfelt work.

Colony Little

Now in its fourth iteration, the Hammer’s “Made in L.A.” biennial provides a cultural snapshot of a city in flux. Curated by Anne Ellegood and Erin Christovale and gathering a diverse group of 33 artists, it’s a bold and thoughtful show. It both carves out a necessary space for new voices, narratives, and ideas to flourish, and challenges its audience to look at Los Angeles through a lens that examines the stories we tell and the myths we sell.

Each of the three artists highlighted here offers unique meditations both on LA itself and the art that is “Made in L.A.”

Installation view of MPA in “Made in L.A.” at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Photo courtesy Colony Little.

The artist known as MPA presents visitors with a compelling conceptual challenge—even before they enter the galleries of the Hammer Museum’s newly opened biennial.

Mounted on the bright white wall at the exhibition entrance, a single lens from a pair of over-sized, cherry-red sunglasses peers out over the Hammer’s open air terrace, reflecting the Westwood skyscrapers that surround the museum. Inside the gallery, the broken remains of the red Wayfarers lean dejectedly against a back wall.

Installation view of MPA in “Made in L.A.” at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Photo courtesy Colony Little.

It’s an apt metaphor for a city that has traded on a self-styled, mythologized image of itself for decades. By shattering the physical shields we so easily hide behind, the artist suggests that there’s room for new narratives, ones that are found in the beauty that lies beyond the artifice. The challenge is to find them.

The broken sunglasses are part of an installation that was inspired by the geological fault lines and fissures caused by actual tectonic shifts, a resonant metaphor in earthquake-prone L.A. Along the floor of the exhibition space, the lines of a red cable dart in and out of walls like a crack shooting through the ground, extending beyond the gallery to the museum’s administration building.

Installation view of MPA in “Made in L.A.” at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Photo courtesy Colony Little.

Within the exhibition space, there’s a fault line of another kind: a wall panel bifurcates the gallery, red-and-green chairs resting on either side of the partition. Four framed openings pierce the wall, opening up to the chairs placed on either side of the divide.

The sense of two sides standing off makes a connection to the ideological polarities that dominate our current political climate clear. Carving a visible space between opposing sides, MPA reframes these schisms, offering viewers a symbolic platform for constructive discourse.

Installation view of Lauren Halsey in “Made in L.A.” at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Photo courtesy Brian Forrest.

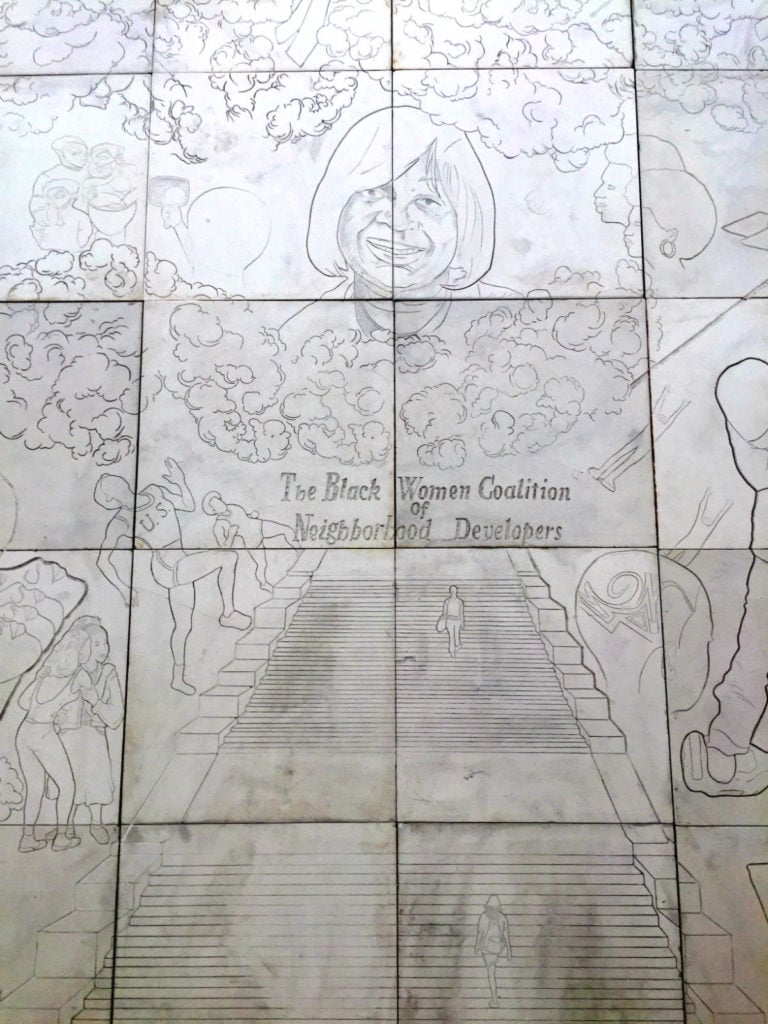

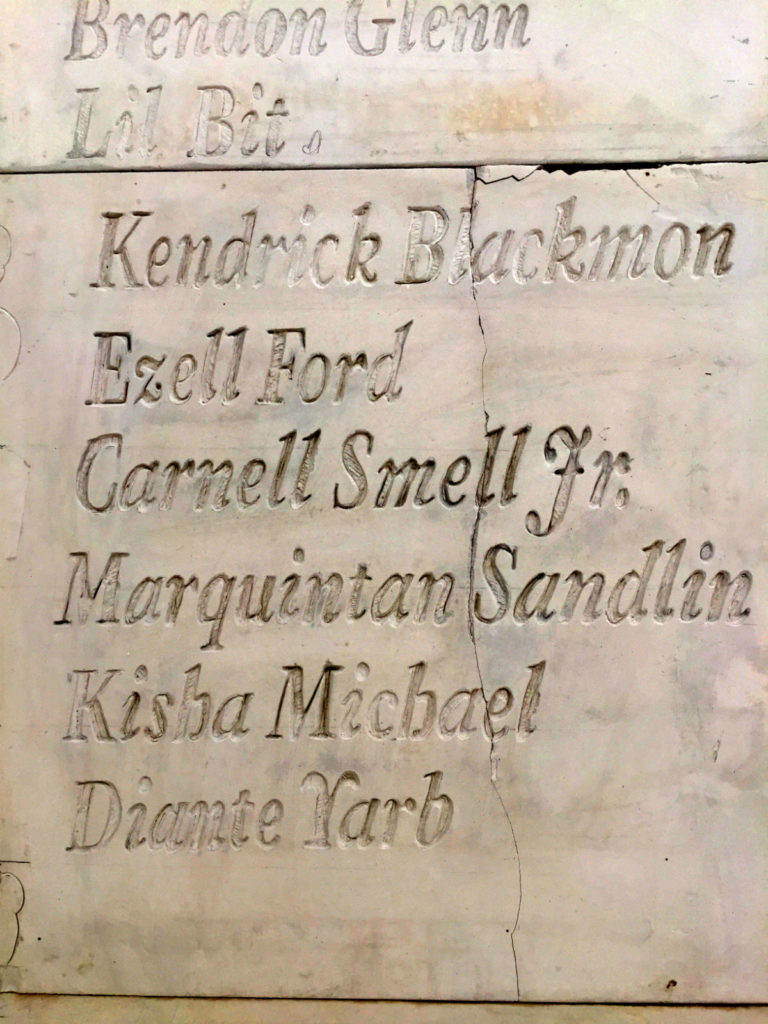

Artist Lauren Halsey is building her own unique platforms for engagement that promote creative space-making in gentrifying neighborhoods. Halsey sculpts fantastical, futuristic installations that preserve relics of a not-so-distant past. She’s currently in the midst of her first solo show across town at MOCA. But for “Made in L.A.,” Halsey has returned to a mainstay in her space-making practice.

On the Hammer’s second-floor terrace, the artist has erected a 20-foot high structure made from square panels of white drywall. The vaulted corridor is covered in the etchings of names, faces, quotations, lyrics, and logos inspired by residents and businesses along Crenshaw Boulevard, an area under threat of cultural erasure as a byproduct of voracious economic development.

Detail of Lauren Halsey’s The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project (2018). Photo courtesy Colony Little.

The carvings preserve a snapshot of a neighborhood in transition, a visible time capsule that both honors the living and preserves the memory of the dead. A number of the square panels also list the names of individuals in memorium, as an homage to those who were killed by the police in Los Angeles, Chicago, New York, and beyond.

Detail of Lauren Halsey’s The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project (2018). Photo courtesy Colony Little.

This structure is a prototype of a large-scale public art installation called The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project, planned for the neighborhood, which will include a series of such towers that will serve as communal gathering places where residents can celebrate, share news—and, Halsey hopes, organize.

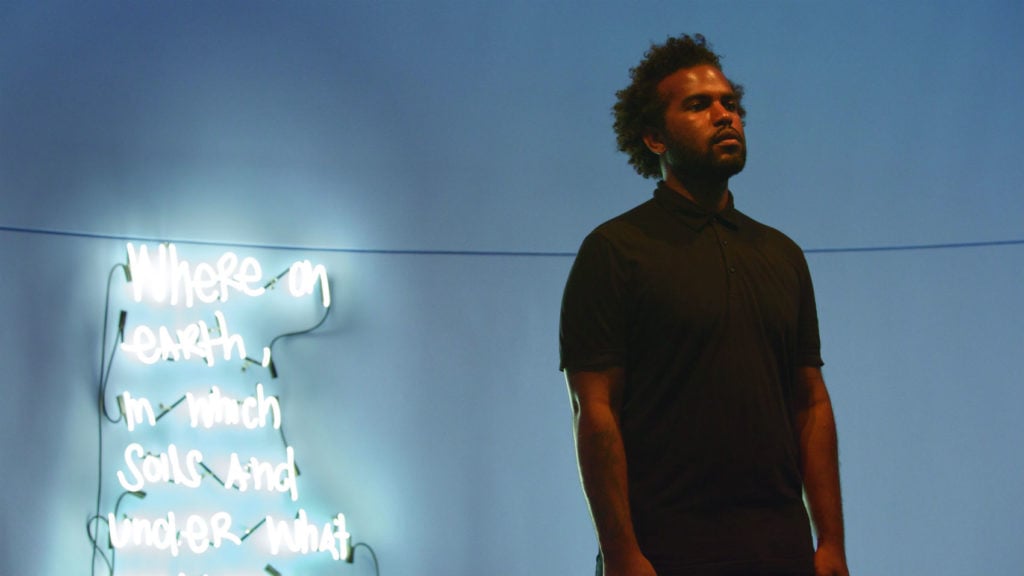

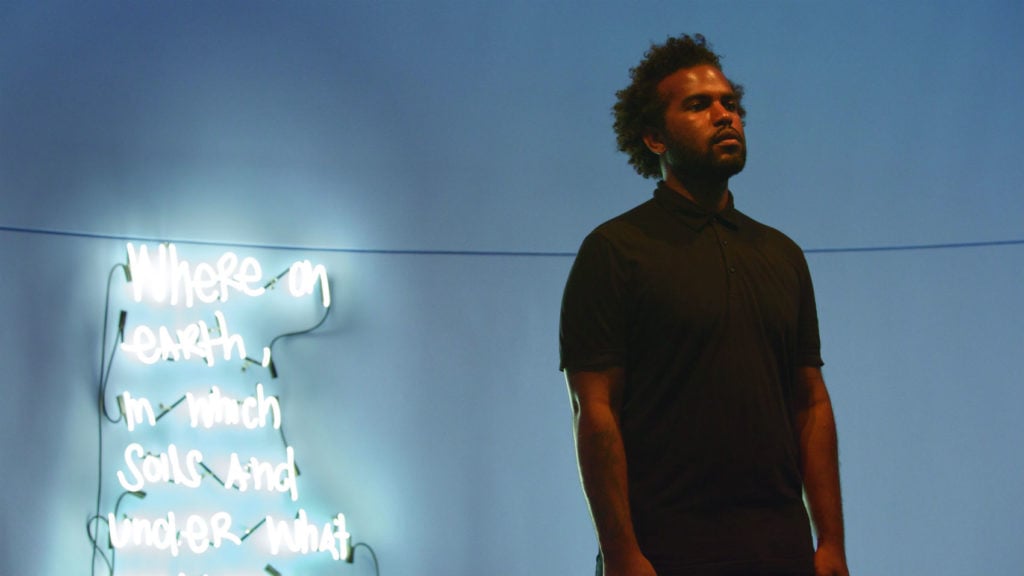

EJ Hill, Excellentia, Mollitia, Victoria (2018). Installation and durational performance. Courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles. Photo: Chisa Hughes.

EJ Hill, whose interdisciplinary practice is anchored in performance, draws on themes of blackness, queerness, and otherness to interrogate the institutions and social structures that perpetuate narrow definitions of identity.

For “Made in L.A.,” Hill’s contribution is titled Excellentia, Mollitia, Victoria. It memorializes a portion of an ongoing performance piece by the artist that attempts to exorcise experiences from his youth that were buried in memory: hostilities and microaggressions experienced as a child that manifest in unresolved pain carried into adulthood.

Installation view of EJ Hill in “Made in L.A.” at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

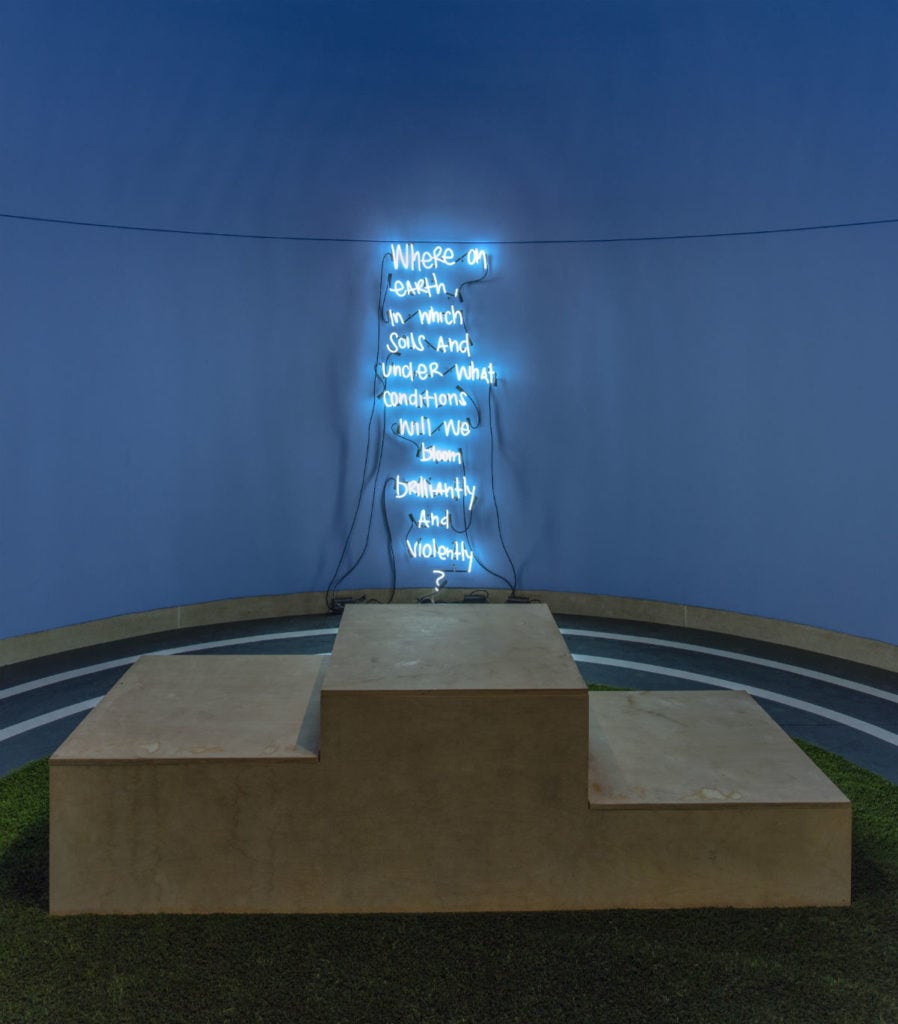

The pathos of Hill’s installation is aided by its location in the Hammer’s small, cavernous vault gallery. That space’s dark walls are disruptively pierced by a bright white neon sign with lettering that radiates in an icy blue haze against the black gallery wall: “Where on earth, in which soils and under what conditions will we bloom brilliantly and violently?”

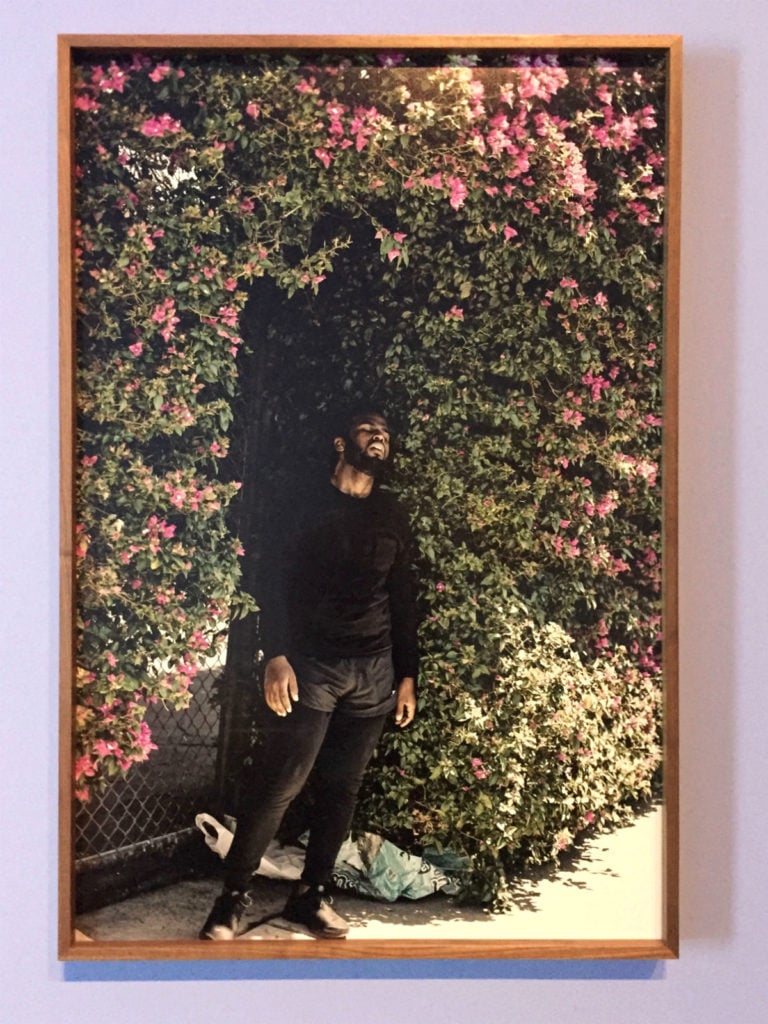

The perimeter of the gallery floor is printed with a black, oval running track. Framed photos by photographer Texas Isaiah line the walls above the track, like distance markers. They show Hill running what he describes as “victory laps” around the campuses of every L.A. school he has attended, from kindergarten to UCLA.

Detail of EJ Hill, Excellentia, Mollitia, Victoria (2018). Photo: Texas Isaiah. Installation view courtesy Colony Little

In these photos, Hill expresses a range of physical exertion, from euphoria to crippling fatigue. This is a hallmark of his artist’s practice, described by the curators of “Made in L.A.” as being rooted in meditative, durational performance that tests the body in the face of hardship. For this particular performance work, he physically activates painful memories, replacing them with a severe trial—ultimately clearing a pathway for healing and emotional growth.

In the middle of the track, in front of the neon sign, a tiered platform resembling a medal podium offers a celebratory hint at what lies at the end of this emotional marathon. Hill’s journey suggests that the race towards acceptance isn’t ultimately against others. It’s with oneself.