On View

Mark Leckey Unleashes His Hyperreal Man-Child at MoMA PS1

It is a relentlessly coded, tirelessly air quoting affair.

It is a relentlessly coded, tirelessly air quoting affair.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

A great deal gets said, wordlessly, about Mark Leckey’s overstuffed MoMA PS1 show in a three-minute black-and-white film called Joey the Mechanical Boy Animation. Beamed onto a wall with a vintage projector on the museum’s third floor, Leckey’s hand-drawn “Joey” continually consumes and evacuates featureless stuff that is fed right back to him via a large machine. Call it contemporary art as scat play.

Leckey’s mid-career survey, which is coolly titled “Containers and Their Drivers” after a song by the Manchester post-punk band The Fall, is a relentlessly coded, tirelessly air quoting affair that takes inspiration from two principal sources. The first is an indiscriminate love of British musical subculture—its alt-yob celebrations are not unlike the navel-gazing acts that drive fantasy football in the USA—and the disaffected cool of Andy Warhol and Jeff Koons. Predictably, when Leckey’s artistic citations slip down the proverbial rabbit hole, critical judgment is left to plash on the surface.

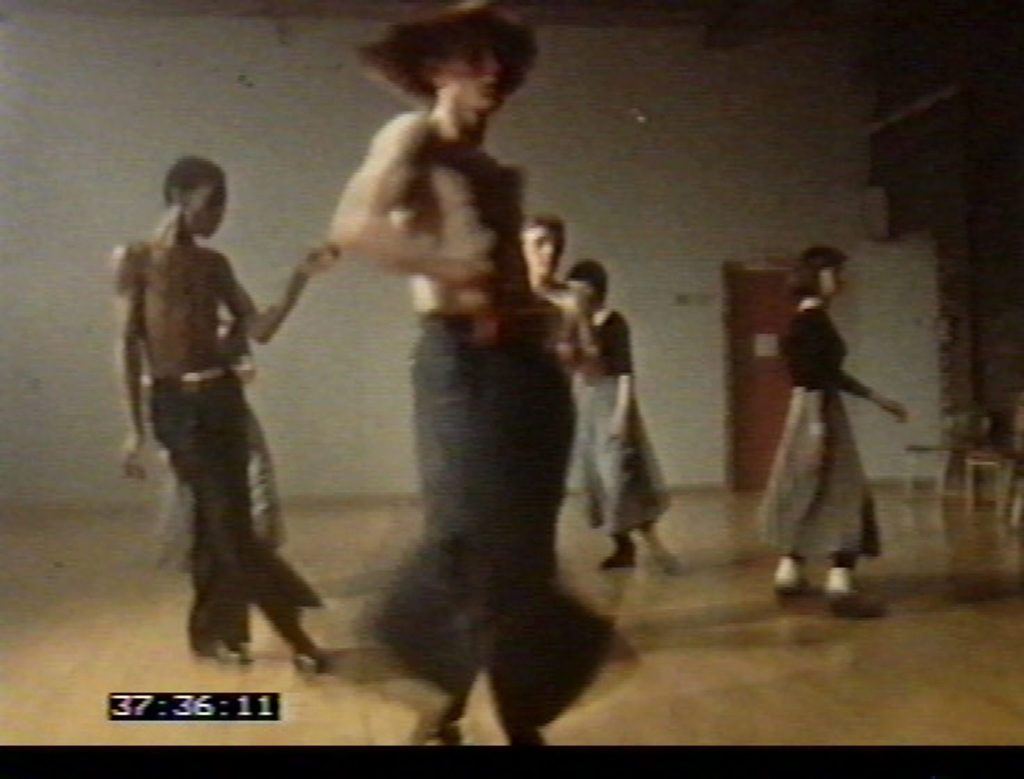

The 2008 Turner Prize winner came to prominence in the UK after making a 1999 video collage called Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore. The fifteen-minute film stitches together footage of mostly working-class, white teenage club-goers throwing shapes and bumping uglies to 1970s Northern Soul and 1990s acid house. Titled after an Italian clothing brand popular with Britain’s fashion-forward “casuals,” the film’s sampling of VHS tapes taps into a recessed but throbbing vein of Sceptered Isle nostalgia.

Mark Leckey, Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1999). Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome. Copyright the artist.

Fiorucci achieved cult status at almost viral speed, thanks in large part to its timely anticipation of the YouTube generation’s breezy manipulations of digital sources. This accident of history lent the North England-born artist the veneer of being the Cezanne of the interwebs—in today’s artspeak, post-internet art’s analog pioneer. A gifted but ultimately trivial sculptor, filmmaker, poster-maker, installation-designer, lecturer, musician and general jack-of-all-0-and-1-art-trades, Leckey seems to have never recovered from the pigeonholing.

Last year, Leckey (mock?) earnestly told the Guardian that his breakthrough film—which serves as a crowd-pleasing anchor for his current survey—was about the notion that “something as trite and throwaway and exploitative as a jeans manufacturer can be taken by a group of people and made into something totemic, and powerful, and life-affirming.” Additionally, he confessed to feeling “joy and melancholy and sweet-sadness” and crying while he spliced together footage.

As with many such unexamined remembrances, one wishes the artist could have seen past his misty-eyed nostalgia and also cried with laughter at the shambolic spectacle of his stumbling, graceless dancers (I did). When in actual sync, their stiff movements respond as much to electronic bass lines as to their being literally drunk or stoned out of their brains on ecstasy. Subversive this film is not, unless youth and drug culture is your idea of sticking it to the man. Rhythmically speaking, it doesn’t hold a glow stick to Soul Train.

Installation view of Mark Leckey: Containers and Their Drivers at MoMA PS1. Photograph by Pablo Enriquez. Courtesy the artist and MoMA PS1.

Leckey’s mini-retrospective is full of such moments: the kind that Urban Dictionary defines as typical of the Man-Child syndrome. A Zac Efron-like fugue state where adolescent adult pursuits are given full wing to ignore their spectacularly co-opted and globally fetishized condition, this disorder consistently mistakes appearances for things, and corporate cultural products—like the soundtrack of the musical “Frozen” (Leckey says it’s one of his “biggest influences”) and billboard-sized Benson & Hedges ads (they repeat throughout the exhibition along with other commercial branding)—for reality.

Traipsing through Leckey’s multiple rooms at MoMA PS1, consequently, comes across as a spiritually exhausting, Reagan-era throwback experience. As captured in his first US survey—co-organized by curators Peter Eleey and Jocelyn Miller of MoMA PS1 and Stuart Comer from MoMA—Lecky’s life’s work takes physical shape as a concatenated set of new media reworkings of Jean Baudrillard’s 1980s-style vaporings. The majority of Leckey’s current installations, in fact, deal with some unacknowledged version of hyper-reality. Were Leckey American, no doubt this exhibition would have featured the DeLorean from Back to the Future.

Being British, the 52-year old Leckey instead dredges up objects, images and sounds from his so-called formative years. Among the items that comprise “Containers and their Drivers,” the following stand out both for their randomness and their repetition: snippets of Kate Bush in various ambient soundtracks; vintage DJ speakers mounted in concert-ready stacks; reworked covers of the British men’s magazine Parade; sculptures of electrical pylons done in cardboard, plexiglass and steel; highway overpasses represented in two and three dimensional media; images of Felix the Cat, a species of cool stand-in for the artist, that recur in films, photographs, collages and, finally, as a massive inflatable.

Installation view of UniAddDumThs (2016). Photograph by Pablo Enriquez. Courtesy the artist and MoMA PS1.

Like the alt-right meme Pepe the Frog, these are among the “containers” and “drivers” Leckey passively invokes. Besides marveling at the reams of found evidence for these “charismatic things”—to borrow the obscurantist lingo of the exhibition’s principal wall text—Leckey takes a pass when it comes to critically assaying their cultural worth, their social value or the mysterious emotional pull they exert on actual human beings.

One instance of this artist’s relentless autobiographical drift is his installation 2016-1964 AD. A set of third-floor rooms dedicated to Leckey’s Liverpool days, it includes a room-filling sculpture of a highway overpass, a hallway illuminated by yellow sodium streetlamps (besides lighting British roads, they also fittingly turn passersby zombie gray), a replica of a front door from one of his apartments, and an LED display of Britain’s national power grid. The result, while genuinely uncanny, is also diffuse and Impressionistic. Its desultory accretion of stuff, when looked at skeptically, can also be read as a blanket denial of authenticity.

Still, Leckey does not arrive at a full tautology, his work’s natural state, until the exhibition’s biggest installation, UniAddDumThs. An abbreviated version of a 2013 project the artist once expansively titled “The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things,” it strives for status as an aesthetic meme for post-internet relativity. An eight-room wunderkammer Leckey “aggregated”— he refuses the term “curate” but won’t acknowledge the pretentiousness of this neologism—from friends, acquaintances and, predictably, Google search, it features 3-D printouts of everything from Amazon shipping boxes to a lumpy Isa Genzken sculpture to William Blake’s death mask.

Installation view of Felix The Cat (2013). Photograph by Pablo Enriquez. Courtesy the artist and MoMA PS1.

“I see myself in a tradition of Pop culture,” Leckey told artnet News contributor J.J. Charlesworth in 2014. “I’m a Pop artist – I believe in the idea that you’re essentially a receiver, that you open yourself up to, and you allow whatever is current to come through you and absorb it into your body and somehow process that, and that’s how the work gets made.”

The work’s chief revelation is as simple as it is uncritical: in our era of data glut, everything is everything is everything. Leckey’s replicas (or are they simulacra?) accrue on repeating shelves and pedestals, one after the other, in ongoing, insistent, recurrent, nearly endless succession.

At the risk of being a reality fundamentalist, this proposition is not just silly but culturally dangerous. Images influence people, objects are different, things mean something, and judgment is important—now more than ever.