Art & Exhibitions

Matisse Cut-Outs at Tate Modern Rewrite Art History

Blockbuster exhibition reveals how the artist invented a new medium.

Blockbuster exhibition reveals how the artist invented a new medium.

Coline Milliard

Henri Matisse (1869 -1964)

Photographer: Lydia Delectorskaya

© Succession Henri Matisse

“An artist should never be a prisoner of himself, a prisoner of style, a prisoner of a reputation, a prisoner of success,” wrote Henri Matisse in his book Jazz (1947). It was with this book that the French painter, then already in his seventies, radically challenged his own practice. Pretty much wheelchair-bound since an operation in 1941, he started to experiment systematically with cut-out paper, honing the method into a standalone technique. For curator Nicholas Cullinan, the artist invented a whole new medium.

Opening at Tate Modern on April 17, the exhibition Henri Matisse: the Cut-Outs—which will travel to MoMA in New York this October—follows the development of Matisse’s cut-outs, from their modest start to the monumental works of the artist’s last years. The cut-outs are presented here as the climax of a prolific career. The argument is well-made. And it convinces. Although they represent only a fraction of the modernist giant’s oeuvre, the cut-outs correspond to a particularly prolific period: Matisse produced about 200 works between 1947 and his death in 1954. They distill the three fundamental elements of Matisse’s work: line, color, and composition.

“Invented” might be an overstatement. By the mid-20th century, paper cut-outs had been around since at least the birth of Cubism, spearheaded by Matisse’s friend and rival Pablo Picasso. The surrealists were also keen collagists. Yet what differentiates Matisse’s work from those practices is the fact that his cut-outs contain no more information than their shape and color. They do not introduce a found image like, say, in Max Ernst’s collages or even a motif like in Picasso’s iconic Still Life With Chair Caning (1912). The pictorial object is created solely by the movement of the scissors and the selected hue.

Henri Matisse, Icarus (1946)

Maquette for plate VIII of the illustrated book Jazz 1947

Digital image: © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Jean-Claude Planchet

Artwork: © Succession Henri Matisse/DACS 2014

At least, that’s true at the end of Matisse’s oeuvre—that of this exhibition as well. The beginnings were much more utilitarian, as demonstrated in the show’s first room. Here Still Life with Shell (1940) is presented as a sketch, for which Matisse had roughly cut out the main elements (an exotic shell, a jug, green apples) in order to refine their positioning. Displayed next to it, the finished work for which the sketch was created is an oil on canvas. Although Matisse had already tried his hand at standalone cut-outs—notably for the abstract cover of the Cahiers d’Art in 1936—they were clearly ancillary to the major project of painting.

It all changed with Jazz. During the war, the artist had left Paris for Nice on the Côte d’Azur, moving on to the smaller town of Vence when Nice was threatened by bombing. There, in the summer of 1943, that he started working on the book. His health was poor and the cut-outs were a less physically demanding alternative to painting. Assistants colored sheets of paper with gouache to Matisse’s specifications, and he would then directly cut into them. The artist called the technique “drawing with scissors,” for want of a better phrase. The electric joyfulness of these images, which picture circus performers and dancers with a riot of color blocks, is particularly striking when considering the context of their making: an ailing artist working in occupied France. And yet joy and an unapologetic lust for life is what comes out of these works, today perhaps as strongly as it did back then.

Matisse’s enthusiasm for the cut-outs grew in step to his familiarity with the medium. He found a project to match his ambitions with the Dominican Chapel of the Rosary in Vence, on which he worked from 1948 to 1951. Matisse was originally approached to advise on the design of a single stained glass window. But, he took over the entire chapel, designing all the stained glass windows, the religious images inside (in black on white, so as not to disturb the colored light coming from outside), even the priestly vestments. Vence’s chapel marked his definitive transition away from painting. Matisse’s last completed oil on canvas dates from 1948. The artist’s began using the walls of his studios to pin his cut-outs, endlessly permuting their arrangements. “An artist should never be prisoner of their own compositions,”Matisse adds to his plea in Jazz. With the cut-outs, he freed himself from the definitiveness of mark-making, be it painted or drawn.

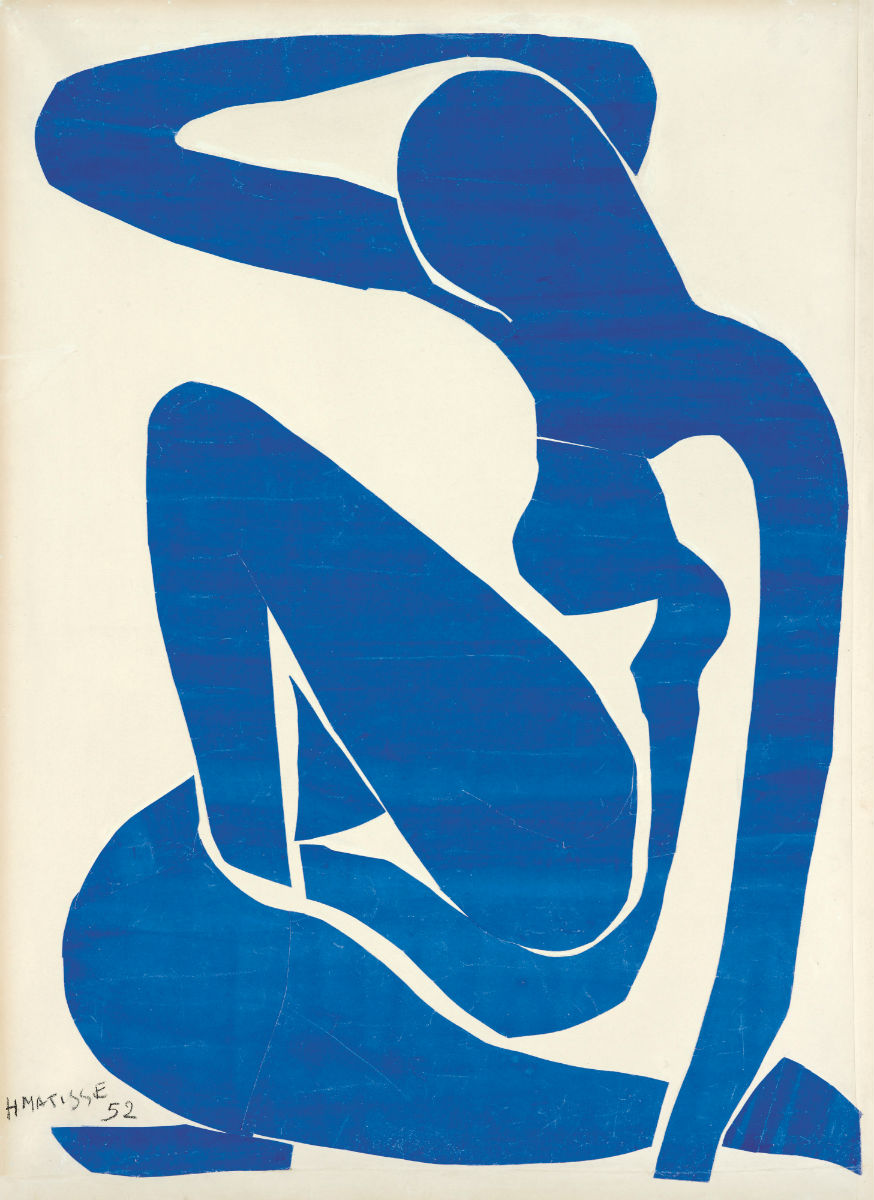

The snippets of film presented in the exhibition show the absolute confidence with which Matisse attacked the paper with his scissors, cutting through the color as if he was following a pattern. In just a few seconds, an acanthus leaf emerges. The artist knew his motifs so intimately that he only had to liberate them from the flat expanse of color. Never is his proficiency more apparent than in the room that gathers his four blue nudes halfway through the exhibition. The chromatic exuberance of Jazz and the Vence stained glass windows have been replaced by a minimal palette. The female form is reduced to its absolute essentials, limbs, torso, head, and breasts. “Simplicity is complexity resolved,” Brancusi once said. Matisse’s blue nudes could not be better described.

The dazzling freshness of the cut-outs may occasionally distract from the fact that these works are works of maturity, and an occasion for Matisse to revisit his oeuvre. The blue nudes hark back to his Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra), a fauvist painting from 1907 that caused much scandal at the time. (Its effigy was burnt at the Armory Show of 1913.) Matisse’s lifelong interest for patterns reemerges in pieces such as Large Composition with Masks (1953), originally intended as the design for a ceramic decoration for the patio of the Brody family in Los Angeles (the piece was turned down: “too big,” they said. It was the more modestly-sized The Sheaf that finally made it to California).

The Snail (1953) also belongs to the monumental collages of the artist’s last years. As he had on several occasions throughout his career, Matisse flirts with abstraction: the big squares of pure colors are only connected to their subject by the barely-there coil-like organization. Memory of Oceania (summer 1952-1953) is almost completely abstract. But the eye, by the end of the show trained to Matisse’s restrained lexicon, picks up—or wants to pick up—the wilted yellow palms of a tree and the ultramarine waves in which the curve of body appears to be diving. The body is a single line.

Art history has tended to present Matisse as a bourgeois, peaceful and pacifying soul, particularly when pitted against the fearsome Picasso. He encouraged the myth, famously saying he wanted painting to be “without any troubling topics,” something for cerebral workers to rest their minds like they rest their bodies “in a good armchair.” But, this superb exhibition demonstrates that radicalism doesn’t have to be violent. From his bedroom, sick and elderly, Matisse led a blissful revolution.