It was Spring 1961 in Yoko Ono’s studio loft and a rope was tied to the radiator. Two men—one the artist Robert Morris, the other filmmaker Robert Huot—struggled on the floor. Morris lay prone while Huot tried to force him up.

The instructions for this event, written by artist Simone Forti, required that one man remain on the floor while the other attempt to tie him to the wall. This “struggleandendurance [sic] piece was quite difficult,” wrote poet Jackson Mac Low, who had been there that first night. The “virtual combat,” recalled Morris decades later, “cancels the possibility of any voluntary, expressive movement.”

In 2015, fifty-four years after Forti’s first “Dance Constructions” concerts, Jason Underhill, her assistant, and his longtime friend Ignacio Genzon struggled on the floor of the Box gallery’s upstairs office in downtown Los Angeles. This time, in lieu of a radiator, rope had been tied to a wooden bar, screwed into the wall. Underhill kept to the ground while Genzon tried to tie him up.

A few times in the video documentation, made because MoMA wanted to acquire Forti’s nine “Dance Constructions,” the artist’s voice is heard off-screen making sure the two friends are okay, but neither performer answers. At one point Genzon’s shoulder knocked a hole in the wall.

The performance ended after ten minutes, the two performers still in a holding pattern, both physically and emotionally spent.

A New Way of Collecting

It becomes clear in watching this later video—no footage of the first performance exists—that the instructions are only part of the equation. The performance requires a focus, and a kind of surrender; there’s no room for dramatic flair.

“What does it mean then to have written instructions?” asks Ana Janevski, the Department of Performance and Media Art curator who shepherded MoMA’s late 2015 acquisition of Forti’s nine “Dance Constructions.” “It’s not always about executing—there’s also body-to-body transmission, a way of thinking, learning and activating.”

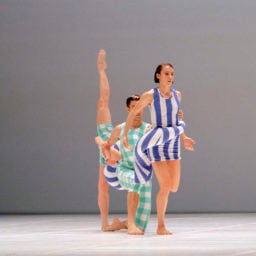

Simone Forti, Accompaniment for La Monte’s “2 sounds” (1961). Performed

in “Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done,” at the Museum of

Modern Art. Performer: Christiana Cefalu. Digital image © 2018 The Museum of

Modern Art, New York. Photo: Paula Court

It took six years, from the time discussions with then-MoMA curator Jenny Schlenzka began in 2009 until the ultimate acquisition. “I’m not holding my breath about it,” Forti said in a 2014 interview, though she clarifies now she never had hesitation about MoMA’s ownership of the works. She just “wasn’t sure the acquisition committee would go for it.” That is, she was not sure MoMA was ready to invest in a live art acquisition destined to always be in flux.

Five of the “Dance Constructions” appear in MoMA’s “Judson Dance Theater: The Work is Never Done,” which opened to the public on September 16. Forti, based in Los Angeles, and five younger former students and collaborators have been in New York for ten days, training the performers and also discussing general teaching strategies for the “Constructions.” Nearly every time MoMA lends the Constructions—which have, in under three years, become the department’s most requested artwork—some version of these in-depth workshops play out.

The Origin of the “Constructions”

Forti devised the “Dance Constructions” quickly and in her 20s, two years after moving from California to New York (away from nature into a “maze of concrete mirrors,” she wrote in her 1971 book Handbook in Motion). She had studied with dancer Anna Halprin in San Francisco and in New York tried studying with Martha Graham. (“I would not hold my stomach in,” she wrote of her time with Graham in Handbook.)

Photo by Warner Jepson. Anna Halprin, The Branch (1957). Performed on the Halprin family’s Dance Deck, Kentfield, California, 1957. Performers, from left: A. A. Leath, Anna Halprin, and Simone Forti. Courtesy of the Estate of Warner Jepson.

She tried working with Merce Cunningham too, determining that he was all about “arbitrary isolation of different parts of the body,” and not for her.

She did connect with the choreographer Robert Dunn, however; his composition class took John Cage’s scores as a jumping off point, and he encouraged his students—including Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, Meredith Monk and Trisha Brown—to write their own scores strategically but not painstakingly. The “Dance Constructions” came out of Dunn’s workshops, and demanded her attention for only a matter of months before she moved on to work that struck an increasingly more intuitive balance between structure and improvisation. But the clarity and repeatability of the “Constructions” made them seminal.

Steve Paxton, Forti’s friend for decades, performed in her first two concerts at Ono’s loft. He participated in Huddle, in which performers climb each other as if climbing a mountain (the instructions explain that they mesh together “as a strong structure. One person detaches and begins to climb up the outside”). Paxton associates the experience with belonging to a swarm of bees.

Forti never used such imagery. “She provided no images at all,” he wrote in the catalogue for Forti’s 2014 retrospective at Salzburg’s Museum der Moderne. “We were performing in a metaphor-free zone. This attitude was new… It seems more intriguing, more pleasurable, to me to encounter work whose source I don’t recognize, of which I therefore have no memory. When such works are encountered, the mind has no tools to assess the experience. It feels naked.”

Forti’s performances, for him, “had that shock.” That the “Constructions,” based on concise written instructions, are also outside of language, adds to the challenge of owning them.

A Living Archive

MoMA’s curators began using the term “body-to-body transmission” to describe the particular somatic communication strategies central to the “Dance Constructions,” which cannot just be taught verbally. While Forti herself doesn’t use that term, it has become synonymous with the “Dance Constructions” over the past few years: department head Stuart Comer uses it, as does Janevski and collections specialist Athena Holbrook. Establishing a vocabulary is necessary for this work, Janevski explains, as it differs from other live works in the collection.

Younger artists like Tino Seghal, Gerard & Kelly, and Allora & Calzadillo have begun to design their works with an eye toward institutional collections. Seghal devises careful instructions for how works should be re-performed; Gerard & Kelly specify how their performers should be paid. In Forti’s case, a plan for acquisition was not intrinsic to the design of the works—nor could it have been, since museum acquisition was not a feasible reality when the “Dance Constructions” debuted.

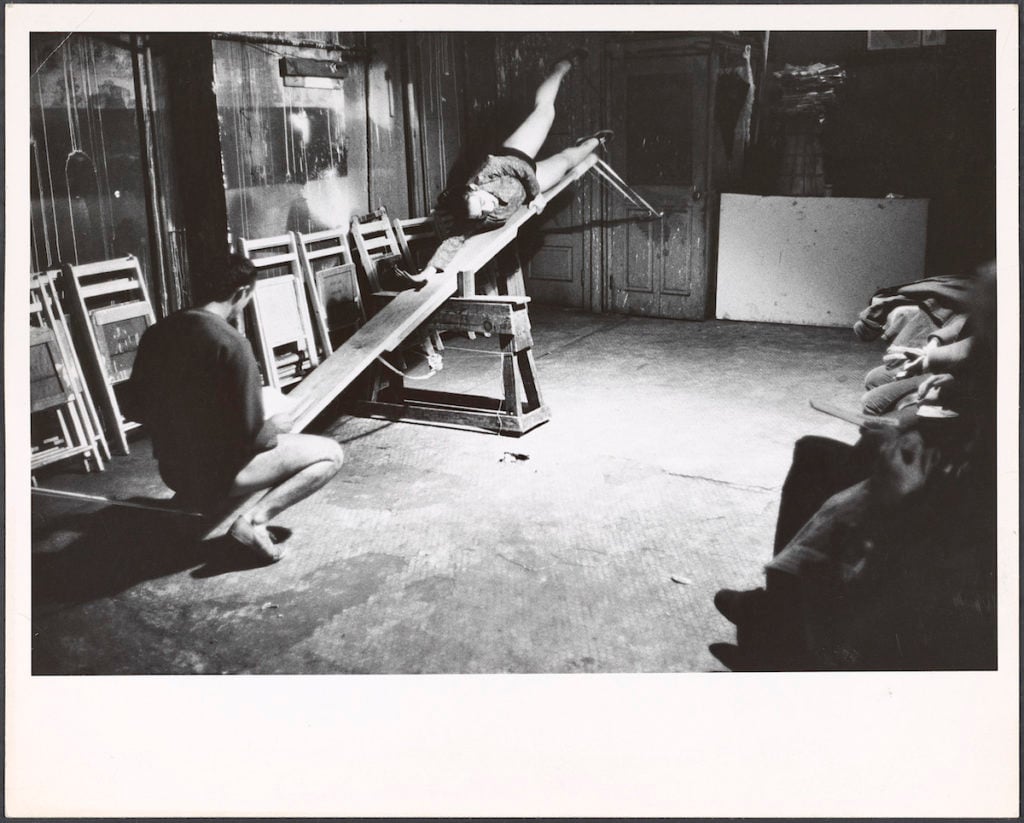

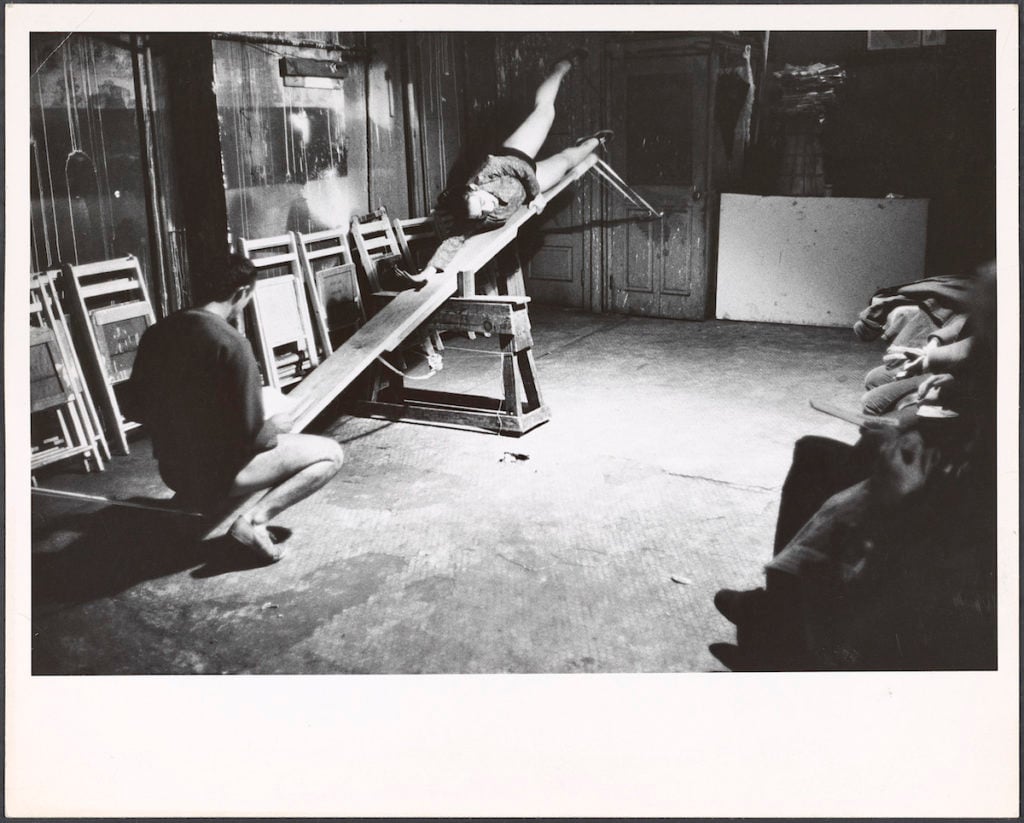

Simone Forti, See Saw (1960). Performed at Reuben Gallery, New York, December 16–18, 1960. Performers: Yvonne Rainer and Robert Morris. Photo courtesy Robert R. McElroy photographs of Happenings and early performance art, Getty Research Institute.

The museum acquired past documentation, the instructions themselves, instruction videos, and extensive writing by Forti when it purchased the “Dance Constructions,” but even all this was not enough. “There are a number of intuitive qualities that you don’t observe from the outside,” says collections specialist Holbrook, who became involved only after the acquisition was finalized. The documentation process would be iterative, and her role in part was to figure out how to archive subsequent performances and the knowledge that came from them.

In January 2016, she traveled to the Vleeshal in Middleburgh, the Netherlands, to document workshops, rehearsals, and performances of the “Constructions” there. Sarah Swenson, a collaborator of Forti’s and, aside from Forti, the principal teacher of the “Constructions” post-acquisition, invited Holbrook to perform with the group.

This affected Holbrook more than she anticipated. “Through that, I became more deeply involved,” she says.

She wrote an essay on the experience. “In stepping into the role of performer,” she explained in writing, “these performances have become part of my physical memory. I am both archivist and archive, documentarian and documented.”

She added that she had become the “institutional memory”—but also that this was an untenable position for any one museum worker to take on. Numerous bodies and organizations had to collaborate to preserve the physical memory of the “Constructions.”

Keeping Faith With the Work

In collaboration with MoMA, Danspace Project hosted a series of workshops in 2016. Judy Hussie-Taylor, Danspace’s director, had been in conversation with Forti about the acquisition since 2012, and she wanted to give a group of younger practitioners direct access to the artist.

“To me this was critical,” she says, “because Forti’s work from 1961 until today is not about ‘instructions’ or ‘lists’ or even an ‘open score’ but, in her words, ‘a certain sensitivity, presence, experience, first-hand knowledge.’” The workshops were open to the public, but also attended by an invited group of dancers already vested in Forti’s work.

“In a way, that was part of the deal, that I would stay active,” says Forti, who left Los Angeles for New York at the end of August and has spent the past two weeks working with Sarah Swenson and four other designated teachers—KJ Holmes, Carmela Hermann Dietrich, Batya Schachter, and Clair Filmon—to train the 20 performers for MoMA’s Judson exhibition. Training takes time, at least a day per “Construction;” the work requires a sensibility that does not come naturally to all performers. “It’s delicate how that gets communicated,” says Forti, “but just doing the instructions and having faith that the piece is there is part of it.”

“There is a real sense of being present, but not in a ‘precious’ or rarified way, but focusing as you might focus on doing something you enjoy around the house,” says Carmela Hermann Dietrich, a frequent collaborator who performed See-Saw—a “Construction” requiring an eight-foot plank and sawhorse—with Forti at the exhibition opening last week.

Over the past ten days, she and the other designated teachers are observing, as they prepare to take more of the responsibility of teaching from as Forti, now 83, no longer travels overseas, and Swenson cannot shoulder the load alone. “It’s an interesting challenge to strip performers of their tendency to ‘perform,’ to create drama,” Hermann Dietrich adds.

That tendency to over-perform, strike poses, and add flourishes has been an issue this week, as it often is. “People start inventing things,” says Swenson, who began teaching the “Dance Constructions” before the MoMA acquisition and now serves as project coordinator as well as principal teacher. (MoMA does not discuss the financial aspects of its acquisitions, but acknowledges that it has budgeted for instructors into the future.) “There are a lot of things not to do. It’s not supposed to be approached in a precious way.”

“The Inspiration and the Fountainhead”

This past week, with Forti and the four teachers present, Swenson led the workshops, then made time for feedback. “It’s brought up questions,” she says.

She notes the conversation that came up around Slant Board, a performance in which three or four people walk up to a ramp to which multiple knotted ropes have been attached. They climb up and down, back and forth for a duration of 10 minutes.

Simone Forti, Slant Board (1961). Performed in “Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done” at the Museum of Modern Art, Performers, from left: Laura Pfeffer, Alexis Ruiseco-Lombera, Samuel Hanson. Digital image © 2018 Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Paula Court.

Swenson has always instructed them to just walk up to the board and get on, but the performance only works if the performers establish an unspoken connection with each other as they move. This wasn’t happening. Forti suggested they all stop and lock eyes briefly before mounting.

The performers tried this for a few rehearsals, before Forti questioned whether it was working. Swenson said she felt it made the performance’s meaning seem too contrived. The gaze was dropped.

Each time MoMA loans or restages the “Constructions,” the requirements differ. They depend on how many “Constructions” will be performed, for how long, and with how many performers. Preparation for the Judson show at MoMA, which includes 20 performers of Forti’s work, required four full days of instruction and then five days of rehearsal. Teams of nine will perform five “Dance Constructions”—Slant Board, Platforms, Huddle, Accompaniment for La Monte’s “2 Sounds” and La Monte’s 2 Sounds, and Censor—at the museum three days a week, three times each day.

Forti herself actually never participated in the Judson Dance Theater concerts. But she debuted her “Constructions” right before, and they played an important role in setting the tone for a moment in New York performance. This, Janevski says, is why the museum felt they were important to own, and steward: “Simone was really part of this community.”

Artist-dancer Yvonne Rainer, who worked with Forti as recently as last year, puts it more strongly: “Simone was the inspiration and the fountainhead.” In her memoir, Feelings are Facts, Rainer wrote of Forti, “I don’t know what her intent was, but for me what she did brought the god-like image of the dancer down to human scale more effectively than anything I had seen.”

“Judson Dance Theater: The Work is Never Done” is on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, through February 3, 2019.