Art & Exhibitions

New York Gallery Beat: Summer Drawing Shows

Shows by Arshile Gorky, George Widener, Louise Despont, and other artists.

Shows by Arshile Gorky, George Widener, Louise Despont, and other artists.

Artnet News

This week, we add a new wrinkle to our regular critical roundups of art in New York, selecting a theme. For the first time out, we assigned our writers to tackle the extraordinarily diverse range of drawing currently on view in the city. They came back with reflections on, among other things, a group show organized around the work of Arshile Gorky in Bushwick, a self-taught “calendar savant” in Chelsea, and camera lucida drawings by a pioneering British polymath on the Upper East Side.

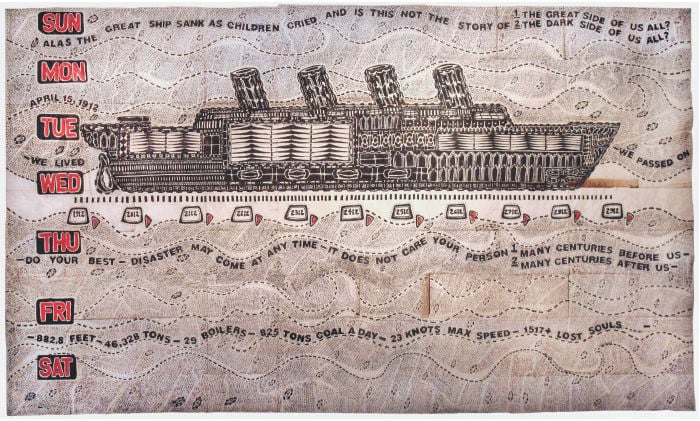

Ion Birch, Order One (2014).

Photo: Benjamin Sutton.

Ion Birch, “Holy Man,” at Horton Gallery, closes July 13.

The draughtsman’s dirty graphite compositions have a beguiling wholesomeness about them, partly because of their playfully stylized aesthetic, which evokes vintage comics, but mostly because of how blissfully happy and innocent all the figures appear. It’s as if someone grafted the heads from a Norman Rockwell family scene onto bodies from a Hustler spread. Interspersed between his expertly executed images of what look like themed sex parties—there’s the paddling orgy, the jungle orgy, the dorm room orgy, etc.—Birch has also created a series of surreal, quasi-mystical vignettes, like the group of women standing alongside a personification of an ancient virility talisman in Holy Man (2014), or the giant, suit-wearing penis-humanoid looking alarmed at the treatment of his puppy-sized mini penises in Order One (2014). Birch proves himself as multidextrous as some of the figures in his drawings, pulling off an improbable blend of erotic, comic, grotesque, and unsettling. —Benjamin Sutton

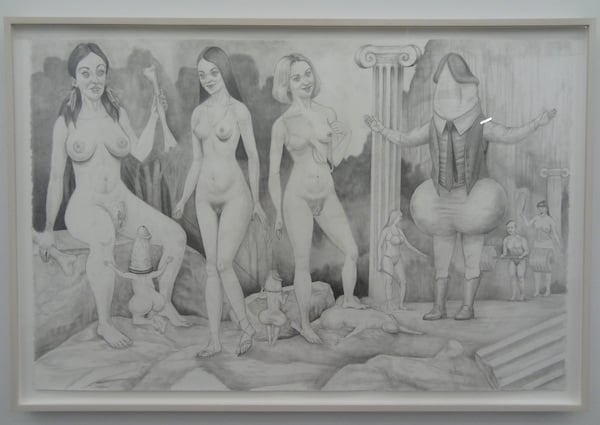

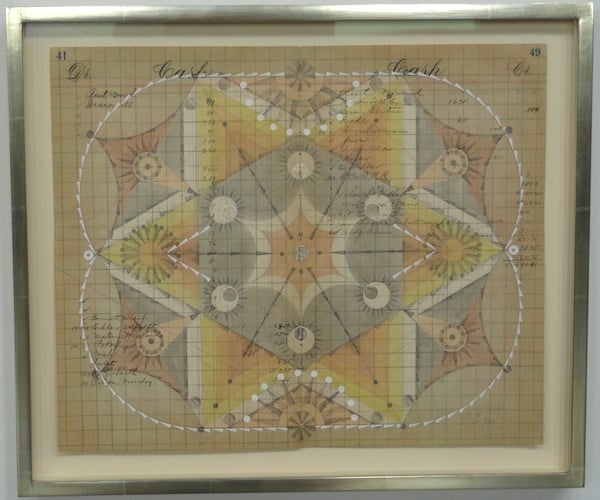

Louise Despont drawing.

Photo: Benjamin Sutton.

Louise Despont, “The Six-Sided Force,” at Pioneer Works, closes July 29.

Despont’s amazing small- and large-scale drawings spread in symmetric, geometric, quasi-abstract patterns of graphite lines, color pencil swaths, gold leaf shapes, and whiteout arrows over antique spreadsheet pages (some in this show date from as far back as 1928). Whereas her previous series consisted of magical musical instruments, here she takes inspiration from one of Rudolf Steiner’s lectures on bees—namely, the idea that their honey contains a concentrate of “the six-sided force,” a rejuvenating energy coursing through all living things. The resulting compositions, sometimes plant-like, occasionally insect-like, and elsewhere entirely non-figurative, offer something for both the aesthete and the intellectual. Their elegant and incredibly satisfying patterns evoke art nouveau designs, while also inviting viewers to decode their hieroglyphics-like markings—not to mention the vintage bookkeeping going on beneath in scribbly cursive handwriting. Despont’s works undoubtedly contain their own potent dose of Steiner’s six-sided force. —Benjamin Sutton

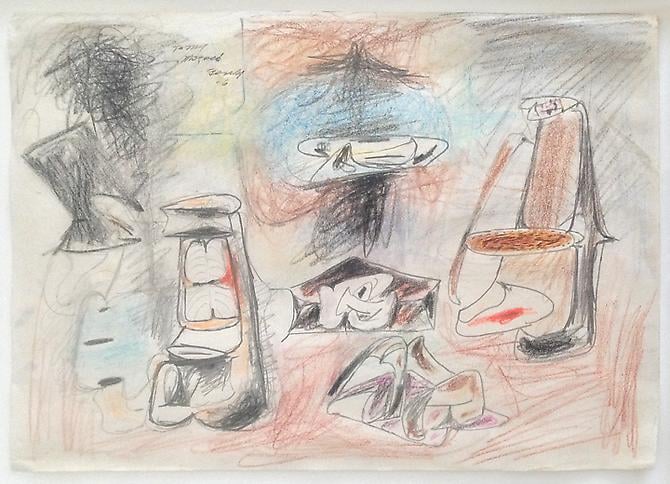

Arshile Gorky, To my Mougouch (dedicated to Agnes Magruder) (1946) Photo: courtesy Outlet

Arshile Gorky and a selection of contemporary drawings, at Outlet Fine Art, closes June 26

Constructing a conversation between a rare Gorky drawing and works on paper from a host of contemporary artists, the viewer is asked to imagine how the contemporary works could have been influenced by their forefather. Remembered for his unique and intensely developed personal iconography, Gorky often extracted inspiration from both his dreams and his nightmares. The central Gorky drawing, To my Mougouch (dedicated to Agnes Magruder), upon first glance appears chaotic and disorganized, but under closer examination reveals a great deal to be inspired by, including bizarre humanoid figures, looming shadows, and what appears to be a pizza. The contemporary pieces range from an austere, perfectly composed mixed-media piece by Hermine Ford to a crude, amusing graphite sketch entitled I Love Cheap Beer by Todd Bienvenu. This breadth serves to showcase Gorky’s subtle and undiscriminating influence. —Cait Munro

Installation view of Kimberley Hart, “Great Rewards,” at Mixed Greens.

Kimberley Hart, “Great Rewards,” at Mixed Greens, closes June 28

Kimberley Hart’s fourth solo exhibition at Mixed Greens is comprised largely of masterfully executed color pencil drawings where all the “action” is centered in the middle of the white page. It as if the objects of her intense focus—a hornworm crawling on a leaf, tugboats in a circle futilely butting heads, a lone sky-blue freight rail car—all look as though they have been plucked out of a larger landscape and suspended in mid-air, which only heightens the magical effect. The back story of how Hart’s real life has become the subject of her works adds another layer of interest: A year and a half ago, the artist and her family moved upstate to fulfill her dream of running a sustainable farm. These drawings represent her attempts to take control of the unexpected challenges she faced and been frank about admitting in the process—dealing with pests on an organic farm the proliferation of deer, rocky soil, or a neighbor’s tractor covered in fungicide. —Eileen Kinsella

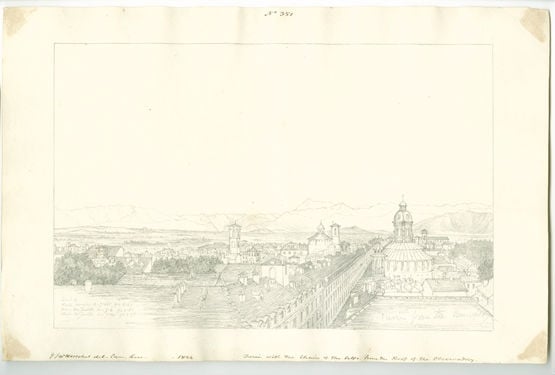

Sir John F.W. Herschel

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, at Hans P. Kraus Jr. Fine Photographs, closes July 31

Photography buffs know the name Sir John Frederick William Herschel. He was a scientist and an astronomer, and happens to be the man who put into practice the use of the terms photography, negative image, and positive image. (He also invented the cyanotype, which became the architectural blueprint.) And paper historians know the name of Englishman J. Whatman, whose good writing paper was often used by early British photographers because it was sized with gelatin, making for improved light sensitivity. The two names can be found in one gallery on Park and 82nd Street in the form of Herschel’s pencil drawings on Whatman’s paper. These 15 pieces from the tail end of the Industrial Revolution are from Herschel’s output of more than 700 drawings completed with the aid of the prismatic reflecting device known as the camera lucida. To sojourn with them is to idle in the company of an exacting polymathic 19th-century intelligence at leisure in Rome, or Lake Brienz in Switzerland, or at the Menai Suspension Bridge off Wales (that piece is watermarked “J. Whatman Turkey Mill”). These drawings were Herschel’s way of keeping a travel diary, and the refinement of the lines—as fine as camelid hairs on an ancient Peruvian textile—is one part technology, 10 parts handwork, and about 50 parts patience. The extended observation process made necessary by the camera lucida is almost inconceivable today. Who can still for hours and take down a scene on paper? Part of the pleasure of these drawings is knowing that there was once a man who could bring such powers of concentration to an appreciation of the world around him. —Elizabeth Manus

Derek Lerner, Asvirus 54 (2014).

Photo: Courtesy Robert Henry Contemporary

Derek Lerner, at Robert Henry Contemporary, closes June 29.

The show is called “Convenient Gratification,” although it’s difficult to see anything that would be convenient about the New York-based artist’s meticulous, hyper-detailed abstract drawings, at least in terms of their creation. From afar, they manage to resemble both outwardly expanding maps and the nebulous blobs of something being viewed under a microscope. But up close, each line that comprises them is a visible testament to the artist’s craftsmanship and dedication. The show is rendered entirely in a dark blue ink, reminiscent of looping classroom doodles taken to their absolute extreme in both size and detail. We can’t but wonder how many pens it took to create these vast, dark lakes, which lie in such complementary contrast to the delicately lined fields surrounding them. —Cait Munro

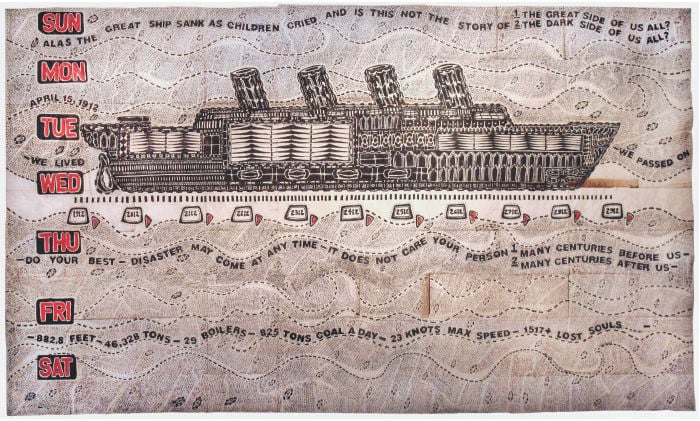

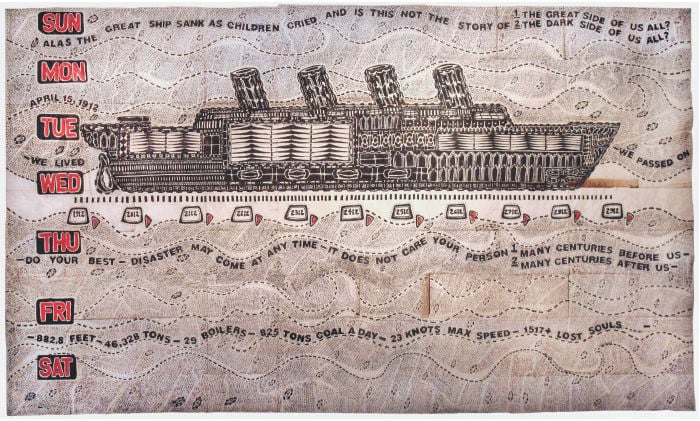

George Widener, Do Your Best (2014).

Photo: Courtesy Ricco/Maresca.

George Widener, at Ricco/Maresca, closes July 5

Even if, like me, you have never before heard the term “calendar savant” you’ll have no trouble believing that this self-taught artist who has Asperberger’s syndrome has been officially diagnosed as one. Widener’s labor-intensive mixed media works practically create entire new universes as they give visual form to his complex calculations based on dates and historical events. These include his three-by-six-foot ink on paper that explores the Titantic disaster Do Your Best (2014) or the even larger two-by-seven-foot mixed media on paper Stream of Time No. 2. (2013), a wild, pictorial depiction of the history of the world. —Eileen Kinsella