Art & Exhibitions

Rich People Hide Their Art in Storage. A Novel Art Space in France Is on a Mission to Get Them to Share It With the Public Instead

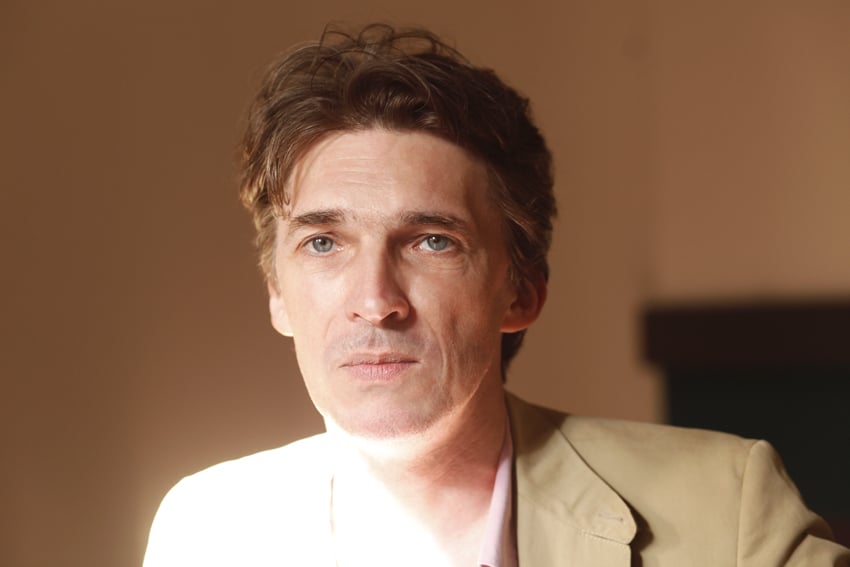

The project is led by influential French curator Nicolas Bourriaud.

The project is led by influential French curator Nicolas Bourriaud.

Naomi Rea

A new museum has opened in France with a radical objective: to make blue-chip works in private collections—the kind typically kept tucked away in storage—public. Undeterred by a heat wave that saw temperatures soar across Europe, some 14,000 people, including the French minister of culture, descended on Montpellier in Southern France on Sunday to attend the inauguration of MoCo Hôtel des Collections.

The Hôtel des Collections is at the heart of Montpellier Contemporain, or MoCo, a multi-pronged cultural development spearheaded by the leading French curator and theorist Nicolas Bourriaud. “We want to empty the freeports,” he tells artnet News, referring to the tax-free warehouses where many high-value works of contemporary art have been destined to languish. “It is a shame that so many amazing artworks, and so many amazing ensembles of works, are hidden,” he says. Making them public, he adds, “is really an ethical drive for us.”

Technically, MoCo Hôtel des Collections is a museum without a collection. (Most people are already referring to it simply as MoCo.) It is, instead, a “museum of museums,” hosting a rotating display of curated exhibitions drawn from private and public collections from all over the world.

Nicolas Bourriaud. Photo ©Henry Roy.

The MoCo project also encompasses Montpellier’s art school, the École Supérieure des Beaux Arts, and the city’s contemporary art center, La Panacée. Together with the Hôtel des Collections, the complex is an “art ecosystem,” Bourriaud says.

The influential curator—who is perhaps best known for coining the term “relational aesthetics”—was the co-founder of the Palais de Tokyo in Paris and is a former director of the city’s prestigious l’École des Beaux-Arts. Now, he is moving outside of the City of Lights on a mission to decentralize France’s Paris-centric art scene.

Bourriaud has followed the money to Montpellier, where the mayor, Philippe Saurel, has embraced contemporary art enthusiastically. He admits that his city, though rich in historical museums and culture, has not been “with it” when it comes to contemporary art.

Now, that appears to be changing. The local government has already committed €22.5 million ($25.5 million) to the project, and will provide €6 million ($6.8 million) toward MoCo’s annual operating costs. The museum is located at the former Hôtel de Montcalm, a 19th-century mansion and former military building, which has been renovated by the French architect Philippe Chiambaretta.

Bourriaud has assembled an all-star team to assist him, including artistic director Vincent Honoré, lured from London’s Hayward Gallery. The president of MoCo is Vanessa Bruno, the well-connected fashion designer, who is tasked with building a network of private sponsors.

Haroon Mirza, Backfade 5 (Dancing Queen) (2011). Fondation Ishikawa, Okayama. Courtesy Lisson Gallery, London. ©Haroon Mirza. Photo by Marc Domage.

As more and more collectors buy art as an investment, an increasing number are keeping their trophies in high-security storage facilities rather than on their walls. At the same time, soaring prices have put works by market darlings beyond the reach of public museums’ acquisition budgets, forcing institutions to play a waiting game to obtain works as gifts or bequests. (Traditionally, many have been reluctant to stage single-collection shows unless a generous gift is anticipated.)

Bourriaud’s museum sidesteps this problem. “You need a huge amount of money to build a collection today, and even if you have as much money as you want, you still are obliged to decide on one point of view, or one period of time,” Bourriaud says. “Here we can completely change our scope three times a year, and present to a totally different idea of contemporary art to the public.”

Bourriaud says that MoCo also offers something different from a private museum, which typically lionizes the tastes of an individual founder. MoCo’s exhibitions will be organized by a guest curator who can offer a new, independent perspective on a collection. For some collectors who may not have the time or the resources to build their own museum, MoCo also offers an alternative.

He also dismisses the concern that his initiative might deprive public institutions of donations or promised gifts. Bourriaud makes it clear that acquisitions are not the end goal in Montpellier. He also stresses that collectors will lend their works by invitation only. “As an institution we don’t want to be passive, we are active,” Bourriaud says. “We are not celebrating the market at all, we are celebrating the passion of certain people who engage with art.”

Any advantage for the collector, such as the prestige of being associated with a museum that might help them gain access to works by an artist with a long waiting list, will be incidental, he says.

Pierre Huyghe, Zoodram 4 (2011). Living marine ecosystem, glass tank, filtration system, resin mask of Constantin Brancusi’s Sleeping Muse (1910). Fondation Ishikawa, Okayama. Courtesy the artist, Esther Schipper, Berlin, and Anna Lena Films, Paris. Copyright Pierre Huyghe. Photo by Marc Domage.

MoCo Hôtel des Collections’ inaugural exhibition features work from a collection amassed by the young Japanese collector Yasuharu Ishikawa, who founded the fashion brand Cross Company. Ishikawa only began collecting in 2011. Called “Intimate Distance,” the exhibition features works by Pierre Huyghe, Haroon Mirza, On Kawara, and Simon Fujiwara, among others.

Bourriaud has pulled off another coup for the museum’s follow-up exhibition in the fall. Next up will be works from the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, which the curator hopes will offer up a different perspective on the Russian public collection.