Art World

The New Mayor of Montpellier Wants to Crunch the Budget for the City’s Premier Contemporary Art Institution

The mayor says the center, run by art critic Nicolas Bourriaud, costs too much money and should focus on different programming.

The mayor says the center, run by art critic Nicolas Bourriaud, costs too much money and should focus on different programming.

Naomi Rea

The future of an ambitious contemporary art institution in Montpellier is in doubt after a local political shakeup.

The French city’s new mayor, Michaël Delafosse, racked with financial concerns, has brought the generous budget afforded to the three-pronged art institution Montpellier Contemporain (MoCo) into question.

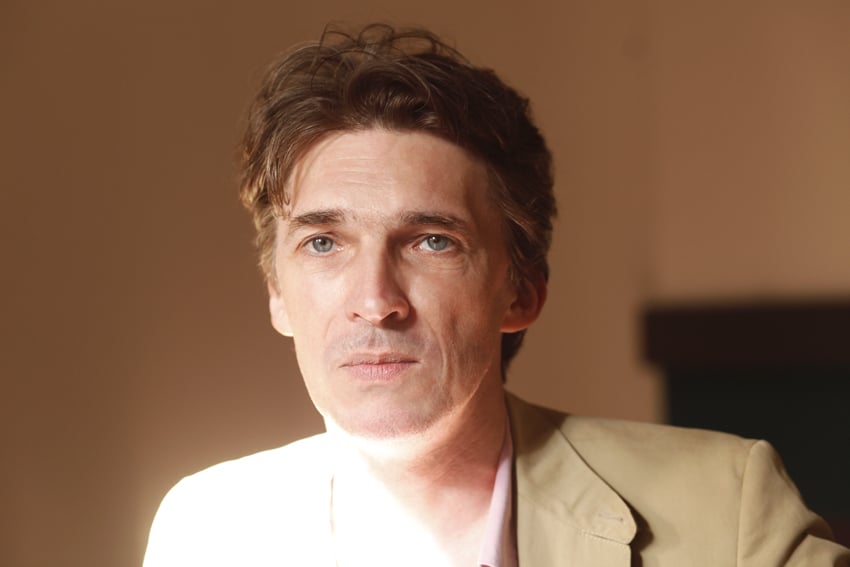

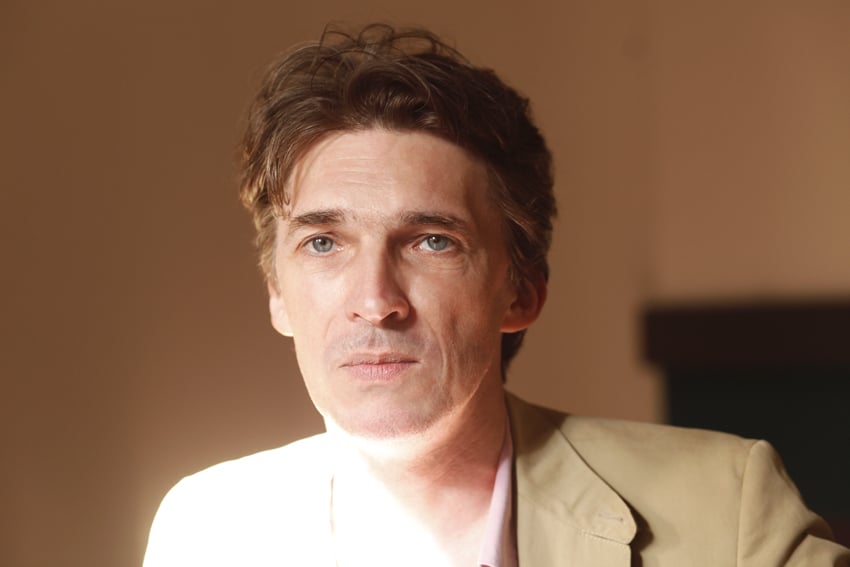

The institution, which is headed by the French critic Nicolas Bourriaud, who cofounded the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, encompasses an art school, a contemporary art center, and the Hôtel des Collections, a venue dedicated to exhibiting public and private collections.

Delafosse, who says he recognizes the value MoCo brings to the city—educating and training artists and curators, offering residencies and employment, and exhibiting artworks—has raised questions about its generous yearly allowance, allocated by his predecessor, Philippe Saurel.

Delafosse is now considering “reorienting” MoCo’s budget, and has launched an open call for proposals to repurpose its spaces. He has also expressed interest in mounting less demanding exhibitions and has suggested a focus on street art, which is popular in the region.

A particular focus of public scrutiny has been the newest part of the institution, the Hôtel des Collections, which is housed in a restored building that was converted at a cost to the city of €22 million. In addition, the space is allocated a €6 million yearly budget. It has thus far had disappointing attendance figures, despite what the mayor has deemed a “more than reasonable” communications budget.

But Bourriaud has defended the figures, saying that the space welcomed 50,000 people to its first exhibition in summer 2019, but that extraordinary circumstances hurt attendance for subsequent shows.

In fall 2019, the “yellow vest” protests forced the museum to close for five weekends in a row, and the most recent exhibition opened a mere week before France’s nationwide lockdown.

The estimated 30,000 visitor deficit has required a €180,000 cash injection from the city to offset.

“MoCo is strong and healthy, and it would be obvious without last year’s strikes and the current health crisis,” Bourriaud tells Artnet News. “Following only one year of activity as a complete institution, MoCo has galvanized the local scene while generating a solid international attention.”

More than 1,200 artists and other creatives from the region have signed a petition defending the institution and rebutting charges of “elitism,” while expressing “alarm and concern” at the mayor’s proposals.

Bourriaud, whose three-year term ends in March, says the mayor’s concerns “will be taken into account” in planning future exhibitions. As for whether he expects his job to be on the line, he says he will apply for a second three-year term “if the conditions for the future development of the institution are met.”

Meanwhile, due to the current lockdown, the institution is extending its current exhibitions, including a show of works from the Cranford Collection and a group show titled “Possessed.“

Next year, the museum plans to open “Sol,” the first edition of a biennial gathering artists from the region. It is also planning shows by Betty Tompkins and Marilyn Minter, and exhibitions of the Sandretto Collection and the works in the Zinsou Foundation.