On View

Matthew Brannon on His 10-Year Quest to Understand the Vietnam War Through Art

His latest exhibition is one small part of an epic research project.

His latest exhibition is one small part of an epic research project.

Julia Halperin

Ahead of the opening of his latest exhibition at David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles, Matthew Brannon sent his dealer what he calls a “cheat sheet” for each work in the show. These are not simple summaries. A sample cheat sheet includes a five-paragraph introduction, copious archival images, and recommendations to read no fewer than four books.

The length of this document—and the fact that reading it feels less like cheating and more like really thoroughly doing your homework—is indicative of how deeply Brannon has delved into his latest subject.

Since 2015, the New York-based artist has been exhaustively researching the Vietnam War. His show at David Kordansky, “Concerning Vietnam,” is the most comprehensive display of work from the project to date. Some of the silkscreen prints—the largest and most complicated he has ever made—span two sheets of paper and require hundreds of screens.

“Anyone who starts research on Vietnam oscillates between feeling overwhelmed and absorbed,” Brannon says. He now sees echoes of what happened in Vietnam everywhere. “I used to feel that when I watched a movie or TV show, there would be a 90 percent chance you’d see infidelity, substance abuse, or cancer. Now that I’ve been studying the Vietnam War for so long, I find it comes up constantly.”

He plans to continue his research for another eight years. Mousse will publish his first book on the subject next spring. A documentary will eventually follow.

For this edition of “Origin Story,” which explores the backstory behind an individual work of art, we spoke to Brannon about one of the most ambitious prints in the show, Concerning Vietnam: Air Force One, November 1963 (2017).

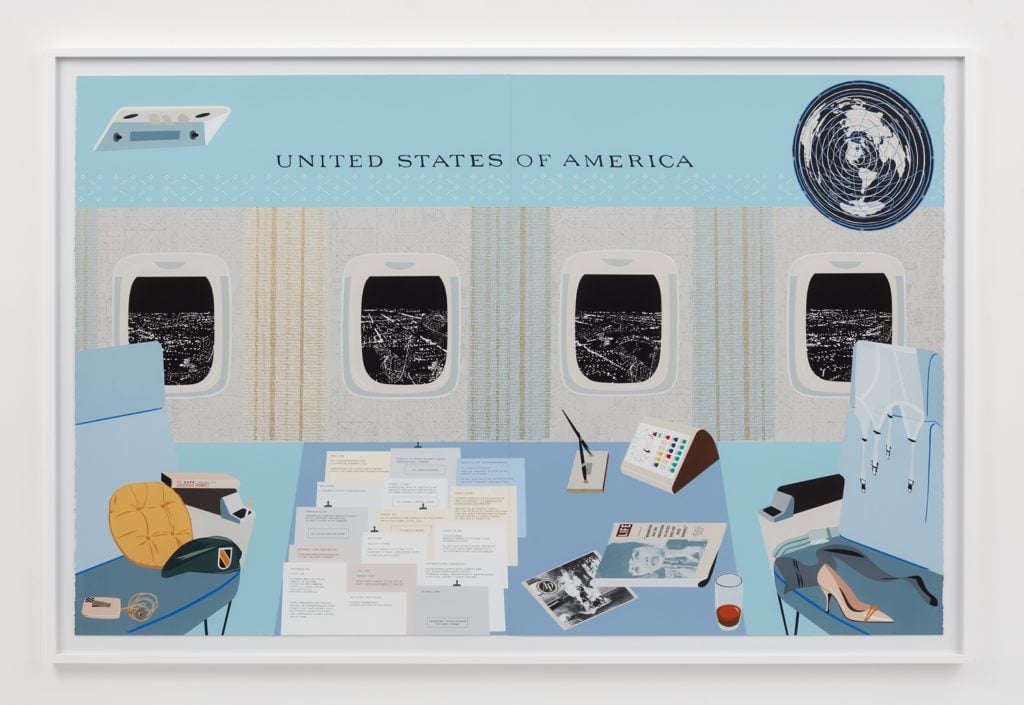

Matthew Brannon’s Concerning Vietnam: Air Force One, November 1963 (2017). Photography: Lee Thompson. Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, CA.

The work imagines what Air Force One would have looked like from John F. Kennedy’s perspective during the final month of his life, when he made the decision to greenlight a coup that would result in the death of South Vietnam’s president. JFK himself would die three weeks later.

How did you first become interested in Vietnam?

I was born in 1971, during the Nixon years, just as he was switching from a strategy to win the war in Vietnam to a strategy to exit. As a young person, nobody I knew spoke about it, including friends whose parents had been in the war. I lived in nine states before I graduated high school, and the America I grew up in is really born from this time period. But it doesn’t reflect well on who we are as a country, so it was a topic that people tended to avoid.

So the research began more as a hobby. Why did you decide it would make a fruitful artistic subject?

I did around two or three years’ worth of reading before I started the series. When it comes to Vietnam War studies, which also involves Cambodia and Laos, it takes—or at least, it took me—about a year to get the basic scaffolding down. It’s so confusing, and it went on for so long. I used to make these maps: “10 Things You Have to Understand in Order to Understand How It All Started.” When I first started the research, I would tell people it may lead me outside the art world. Unfortunately, I can’t help but be an artist. In a way, the artwork is less about showing people what I know than it is about organizing the information in my own head.

President John F. Kennedy flies over Passamaquoddy Bay in Maine, October 19, 1963. Cecil Stoughton. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

How did you develop this particular tableau aboard Air Force One?

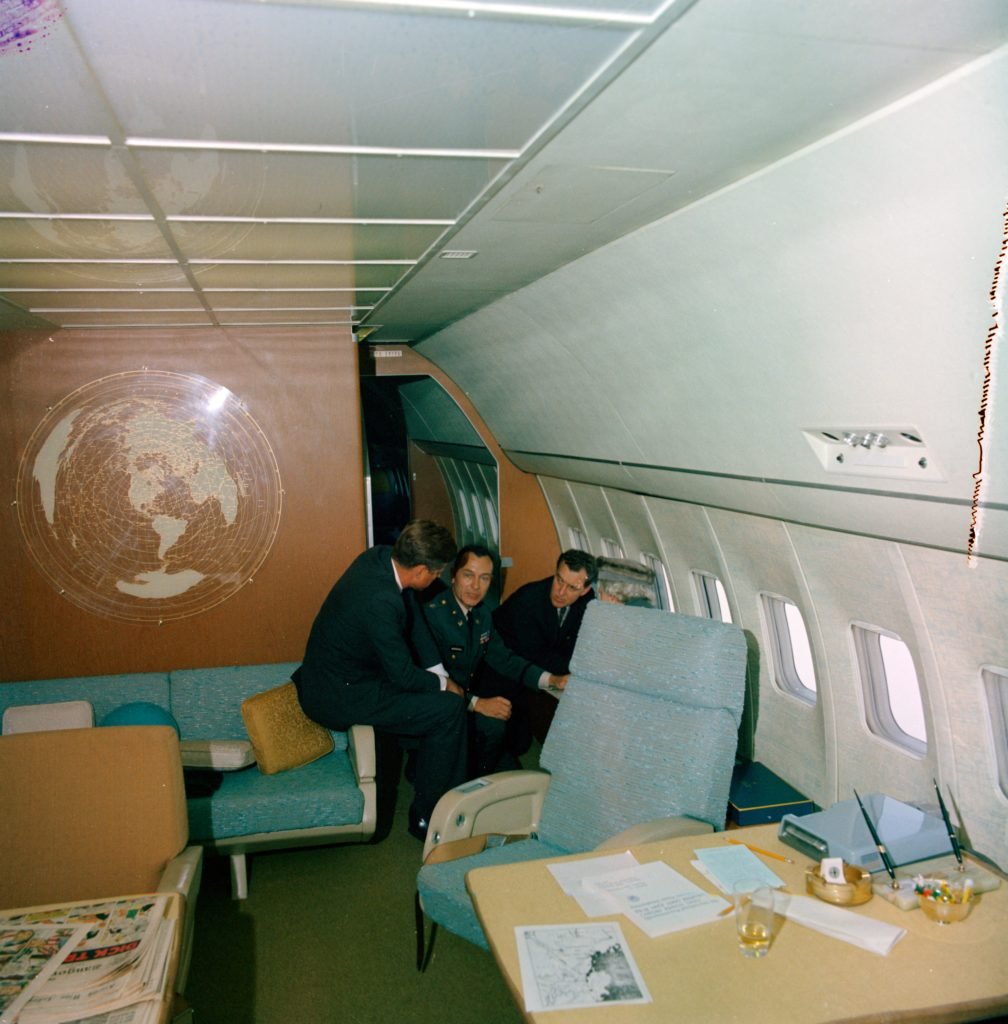

Over the past couple years, I came up with this idea of trying to put myself, or the viewer, in the perspective of the decision-maker. In this case, we aren’t in the Oval Office, but in Air Force One. John F. Kennedy was the first to use the Air Force One SAM 26000, the first plane ever designed and customized for a US president. He really saw himself as a traveling president. Jackie [Kennedy] worked with a designer to develop the interior and the color palette that you see. In a pre-digital age, I love imagining the job that never stops, even when you are flying across the sky.

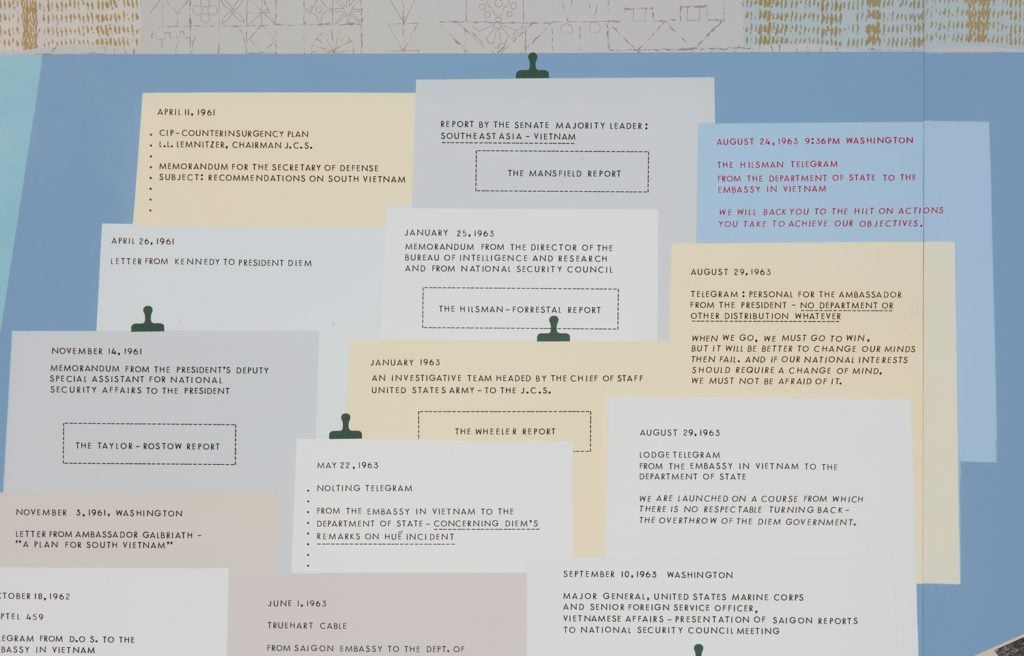

Matthew Brannon’s Concerning Vietnam: Air Force One, November 1963 (2017), detail. Photography: Lee Thompson. Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, CA.

Why make the papers the focal point?

The overall goal with this print was to convey both the US’s complex involvement with South Vietnam and offer a taste of how decisions were made. Each of the documents, from 1961 to 1963, is real and spread out in chronological order, although the font and colors are my own. I put the key document in that purplish color—the one where the US let the people planning the coup know that we wouldn’t get in the way of their plan to assassinate the South Vietnamese President, Ngo Dinh Diem.

I wanted to show how, as president, there is this tidal wave of information that’s coming at you constantly. One of the biggest misconceptions about Vietnam is that people didn’t think it through and weren’t well informed. Actually, it was almost the opposite. No war has been more agonized over than this one.

Are you trying to create a faithful representation of how Air Force One looked at the time? If so, how do you do that?

First, I do as much research as I can, and then I make decisions that play off that accuracy and make changes for the compositional benefit of the print. All the prints refer to a specific month, so I tried to find photos of JFK on the plane at that moment. I might spend an entire day trying to find original images of the right phone. In this case, I drew on photos of Air Force One published in LIFE magazine. But there’s no visual index—you won’t find a real photo from this vantage point. It’s patched together from multiple sources.

Matthew Brannon’s Concerning Vietnam: Air Force One, November 1963 (2017), detail. Photography: Lee Thompson. Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, CA.

Can you point out some of the historical Easter eggs in the print?

The hearing aid on the left-hand chair in the corner is a reference to William Averell Harriman, the former ambassador to Moscow who was among those pushing the hardest to assassinate Ngo Dinh Diem. At this point, he was a bit older and was notorious for turning his hearing aid on and off whenever he wanted. The globe is a motif from the real Air Force One. I think it’s interesting that it has the US at the very center of the globe.

Matthew Brannon’s Concerning Vietnam: Air Force One, November 1963 (2017), detail. Photography: Lee Thompson. Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, CA.

What about the dress and heels on the right chair?

It’s kind of a cheap shot, but you won’t read a biography of JFK where his affairs don’t come up. It’s interesting to read now that the press would never report on them even though they were constant and not very hidden. It doesn’t have anything to do with Vietnam, but in some way it shows you that the decision-maker is still very human.

“Origin Story” is a column in which we examine the backstory of an individual work of art.

“Concerning Vietnam” is on view at David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, until October 21.