On View

Why Peter Hujar’s Photos Feel So Resonant Right Now

"Speed of Life" at the Morgan Library and Museum has touched a nerve.

"Speed of Life" at the Morgan Library and Museum has touched a nerve.

Ashton Cooper

The Morgan Library’s much-praised Peter Hujar show has been a constant source of conversation since opening at the beginning of this year and, naturally, it came up during recent studio visits with artists Scott Treleaven and Paul P., both of whom have shown their work alongside Hujar’s in the past. While acknowledging their love of the photos, they wondered, after all the shows of Hujar photographs over the past 15 years (including an exhibition at MoMA PS1 and several solo shows at galleries), why has this particular show received so much adulation?

Is it the thoughtful installation? Is it the inclusion of a wide breadth of his work? Is it our obsession with seeing the real Manhattan of the ‘70s and authentic artists who never sold out? Or is it simply that Hujar’s work says something to us in this particular moment that we need to hear?

These questions were on my mind during multiple visits to the show in question, which is composed of 164 black-and-white photographs that hang in a single room painted a warm grey, making it feel not just manageably sized but also intimate, private. The installation is indeed incredibly well conceived, allowing for viewers to appreciate repeated subject matter or visual motifs without feeling spoonfed.

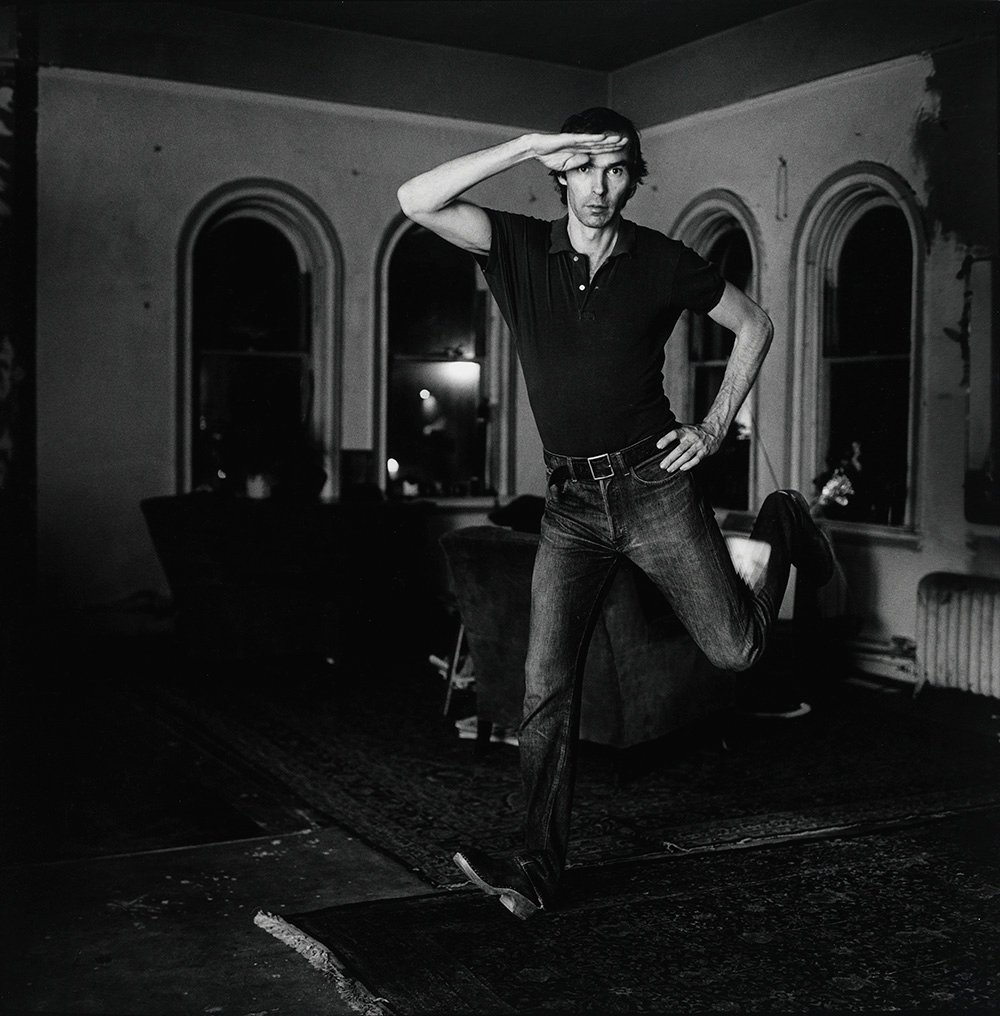

Peter Hujar, Susan Sontag (1975). © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and Fraenkel Gallery.

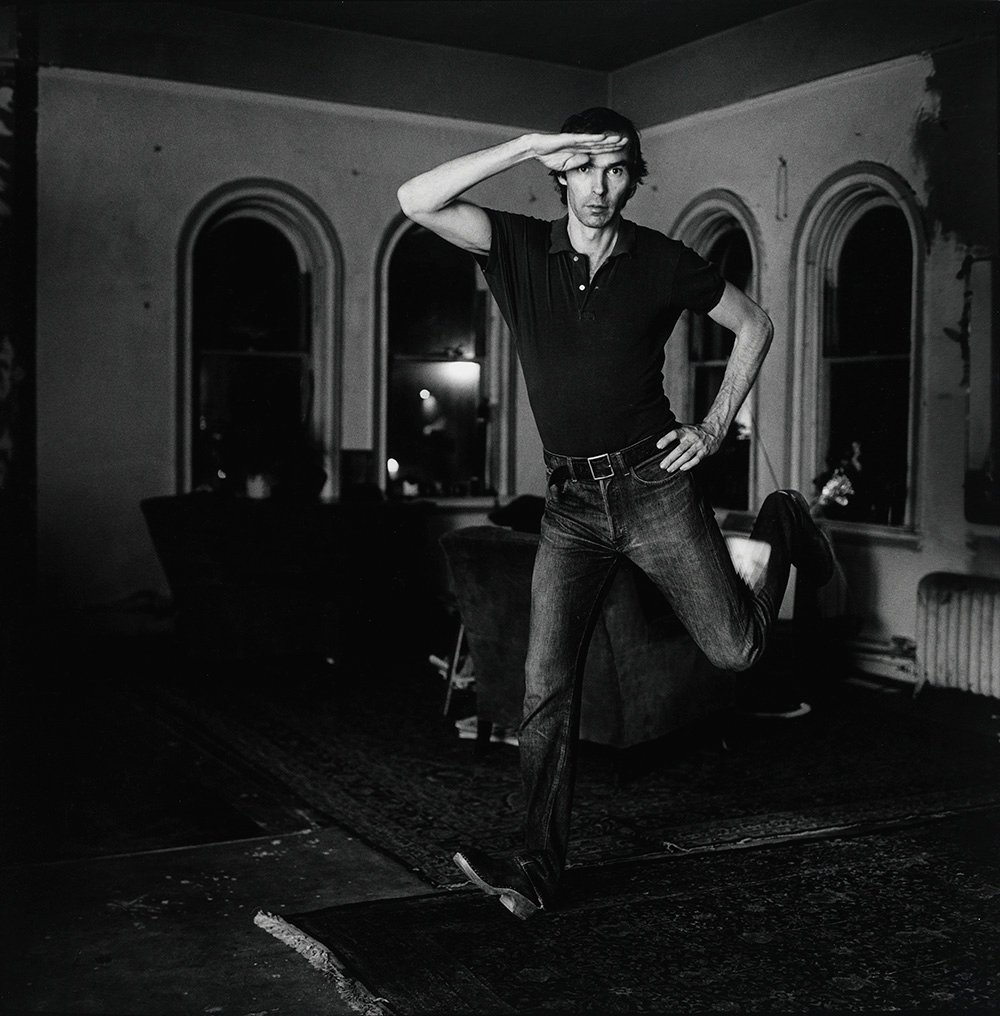

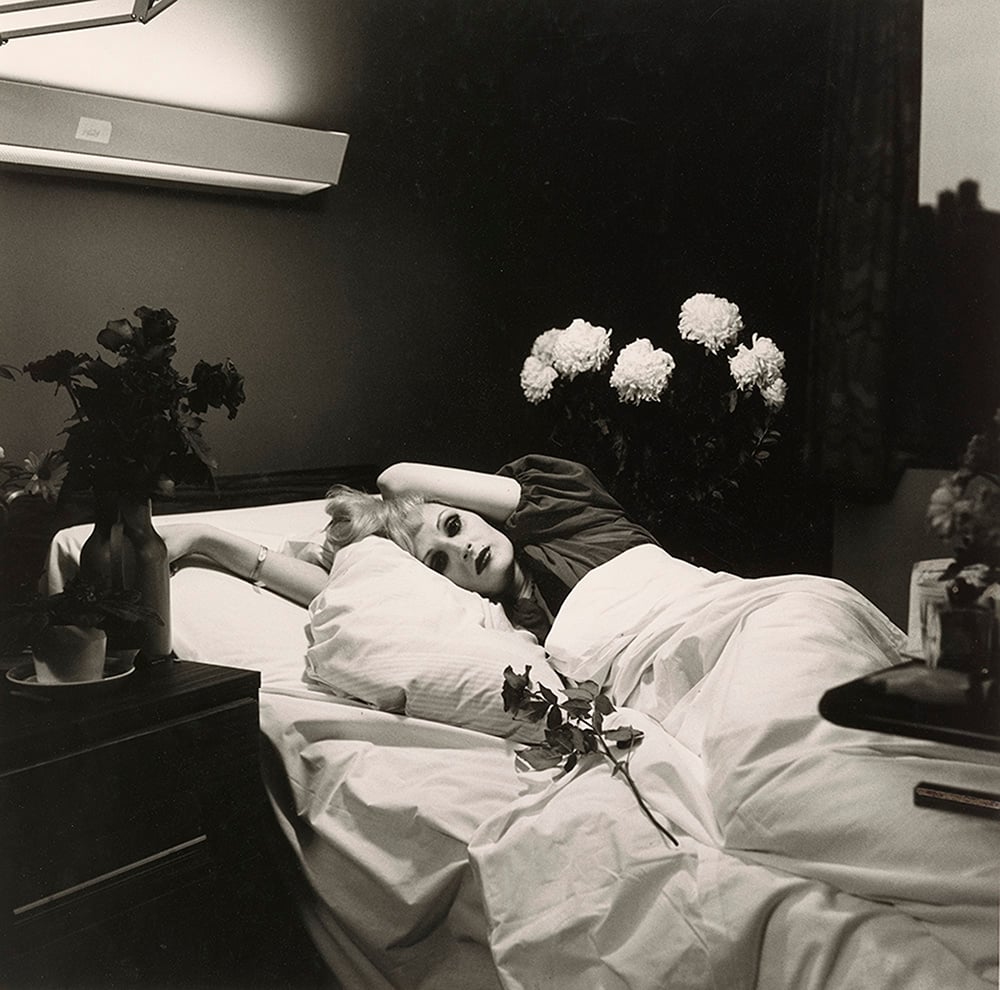

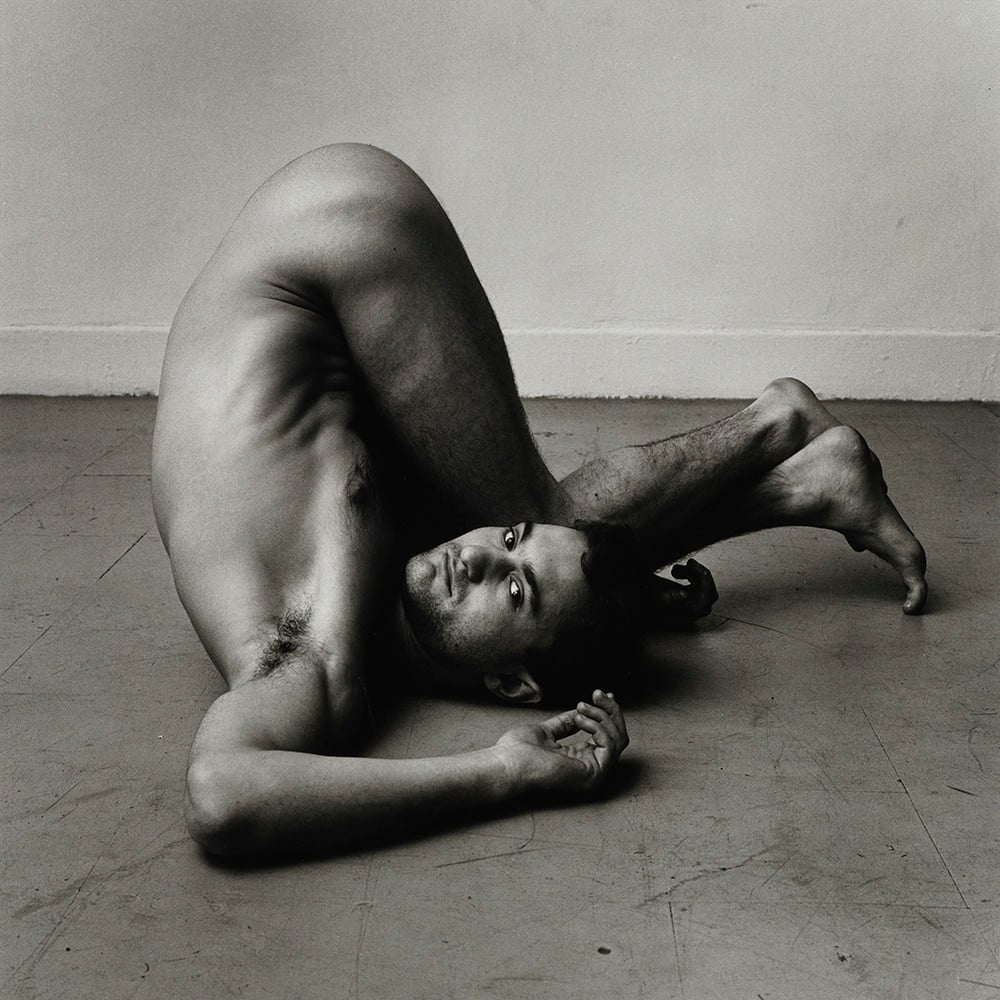

One especially effective display choice is hanging a single image—often an iconic one, such as Hujar’s well-known 1975 portrait of Susan Sontag seductively reclining in a ribbed turtleneck—to the left of a grid of four works that elaborate on its content. To the right of the Sontag portrait, for example, are portraits of Fran Lebowitz, from 1974; Charles Ludlam, from 1975; Bill Elliot, from 1974; and Dean Savard, from 1984, all in states of languorous repose. Taken together, they make a bewitching group of masculine-of-center bodies enacting poses conventionally left to the female nude.

Another well-conceived aspect of the installation is the grid of 40 photos on the back wall that anchors the exhibition in Hujar’s own method of hanging the works. Hujar preferred to show the works in a grid that incorporated a mix of subject matter, as in his last exhibition at Gracie Mansion Gallery in January 1986, shortly before he died of AIDS-related pneumonia. Curator Joel Smith has made a clear choice to hang the entire exhibition following Hujar’s own preference for intermingling images of humans, animals, cityscapes, and photos of the Hudson River.

Peter Hujar, Hudson River (1975). © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and Fraenkel Gallery.

In a portrait of Edwin Denby from 1975 that depicts the lithe poet and dance critic in his later years, Hujar photographs Denby with tousled hair sitting up in bed. Using an extremely shallow depth of field, Hujar captures just Denby’s face and a bit of his protruding shirt in focus. This shallowness even excludes Denby’s ears, which in their fuzziness are pushed to the background. The effect of all of this is to make me feel like I’ve leaned my own face in so close to Denby’s that I’m just able to perceive the immediacy of his eyes, nose, and mouth. Hujar has created the feeling of a private moment between Denby and me, a feeling of shared bodily proximity.

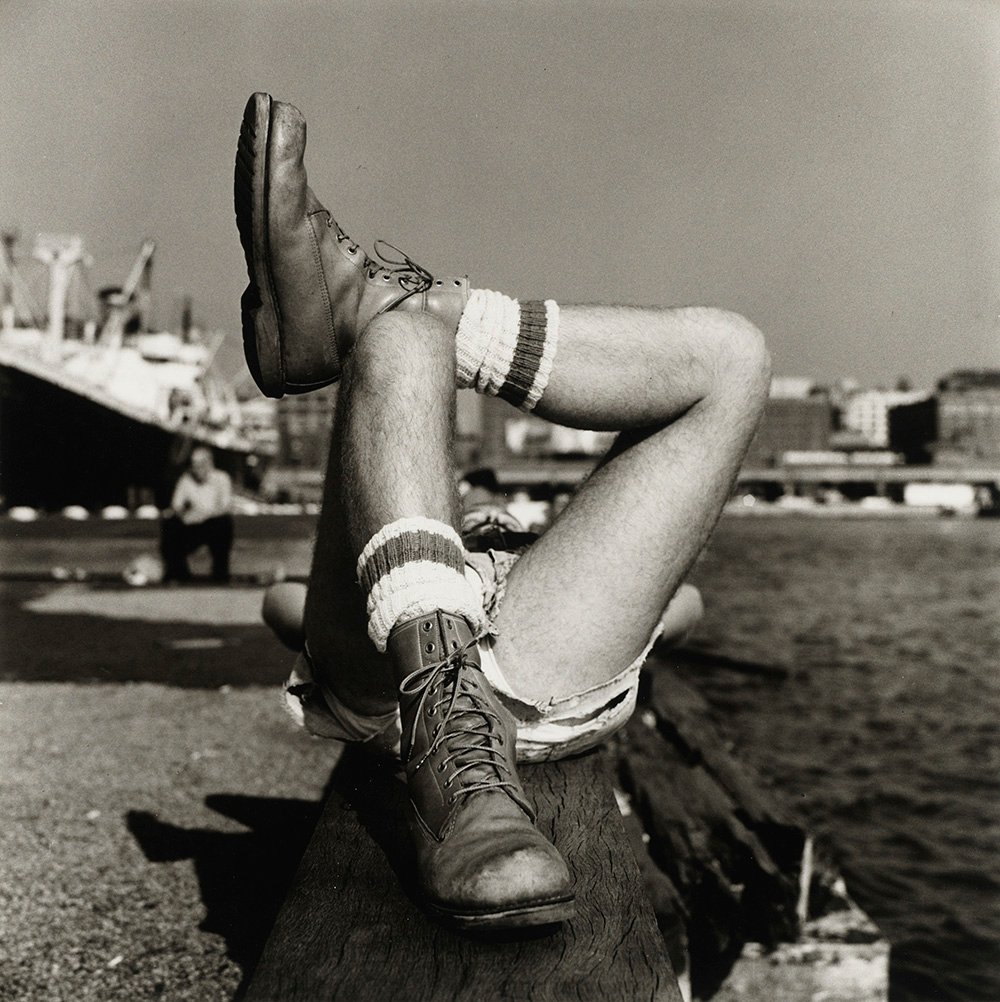

In Randy Gilberti’s Legs (1981), the photo shows its subject’s legs from the knees down with the subtle indentations left by the socks’ elastic evident on his ankles. “I want people to feel the picture and smell it,” Hujar said of his approach to the nude.

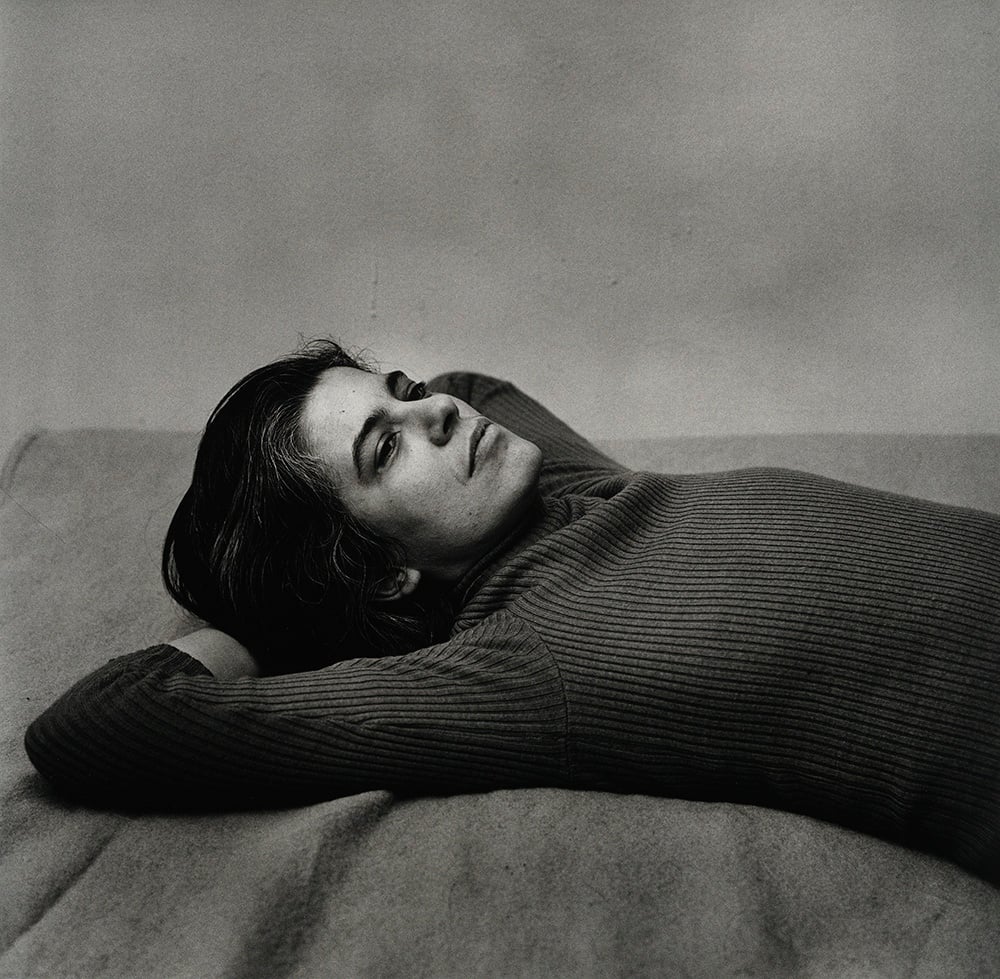

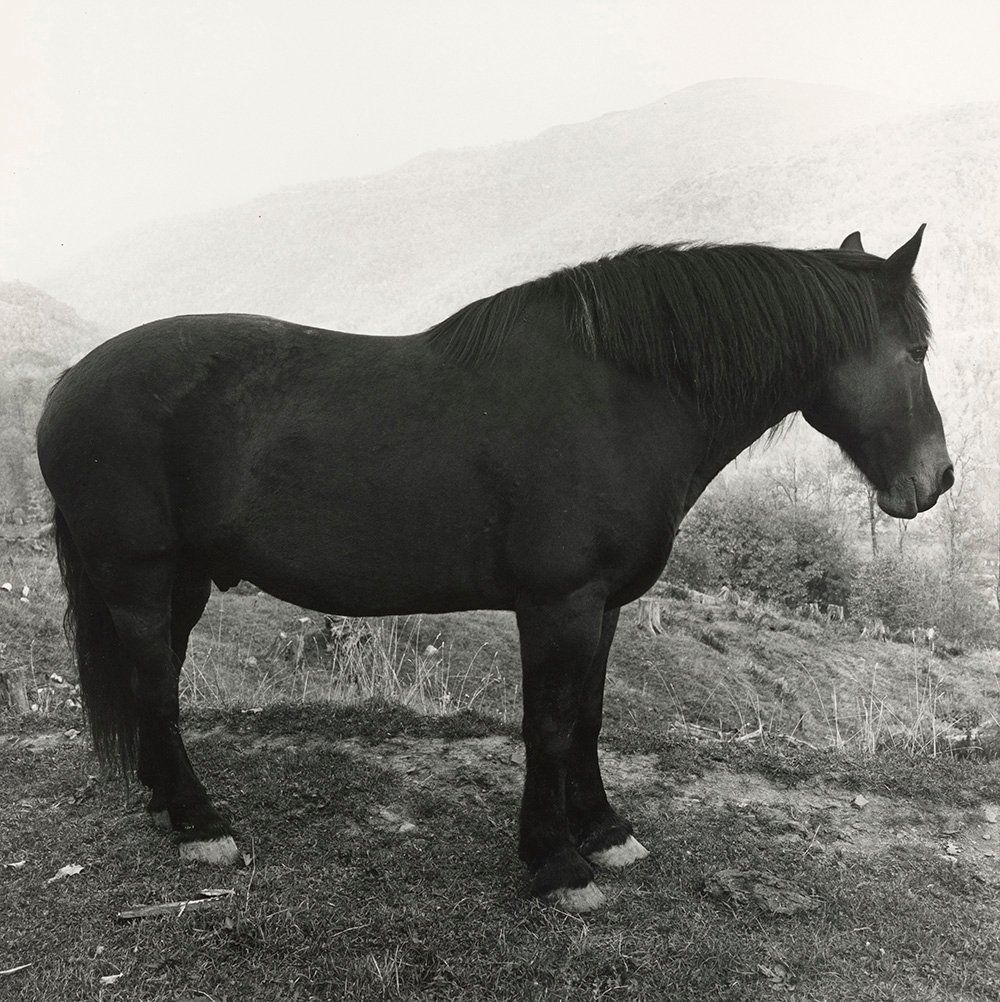

One of the pleasures of this show is discovering that Hujar’s attentive tenderness also extends to his many portraits of animals. In Goose—Germantown (1984), Hujar uses a depth of field similar to the intimate Denby portrait. The titular white goose faces the camera, looking directly into the lens, its eyes, beak, and bulbous chest in focus, while the sparse landscape blurs in the background. There are several other striking animal/human juxtapositions throughout the show: Horse in West Virginia (1969) and Reclining Nude on Couch (1978) or Great Dane (1981) and Nude Backstage (Ridiculous Theatrical Company, “Eunuchs of the Forbidden City,” Westbeth) (1973).

Peter Hujar, Horse in West Virginia Mountains (1969). © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and Fraenkel Gallery.

If portrait photography is stereotypically discussed in terms of capturing something revealing or true about the sitter that can only be seen with a camera, Hujar is making an argument for another function of the portrait. He isn’t after Truth, but allowing people to be vulnerable, to share something small of their private selves. Hujar’s photographic look is tender.

I’m sure his work feels urgent to many of us right now—especially those with bodies that are marginalized and threatened—for a multitude of reasons, but it is this gentleness that stands out to me. Hujar’s photography memorializes and monumentalizes acts of tenderness and moments of vulnerability, things that lately feel less and less practicable and, for that reason, more and more important.

“Peter Hujar: Speed of Life” is on view at the Morgan Library and Museum, through May 20, 2018.

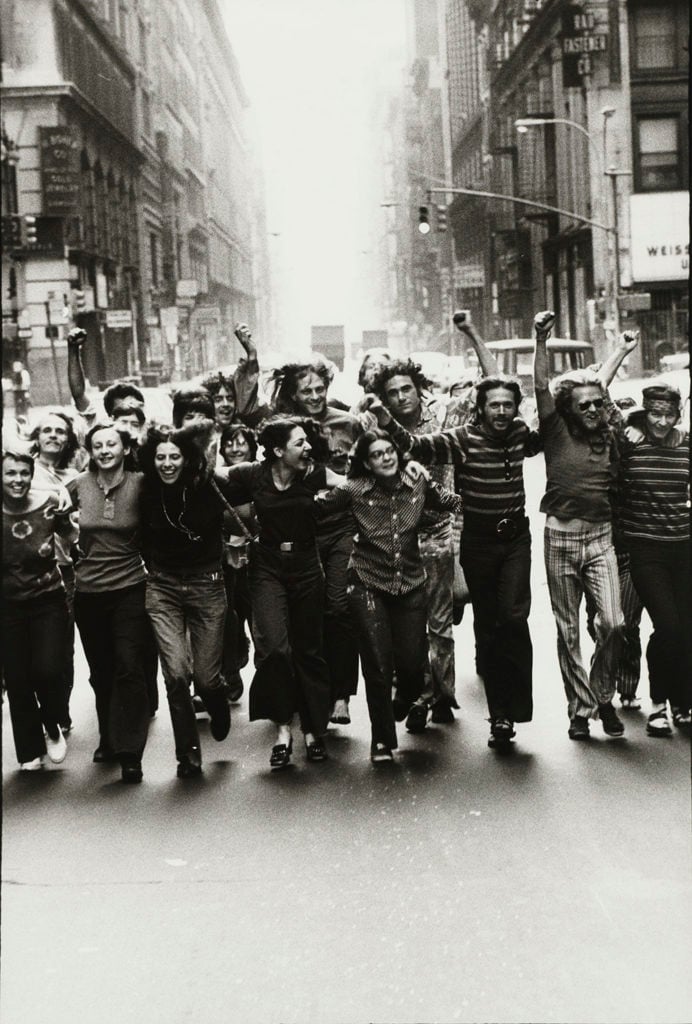

Peter Hujar, Gay Liberation Front Poster Image (1969). © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and Fraenkel Gallery.

Peter Hujar, Candy Darling on her Deathbed (1973). © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and Fraenkel Gallery.

Peter Hujar, Christopher Street Pier (2) (1976). © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and Fraenkel Gallery.

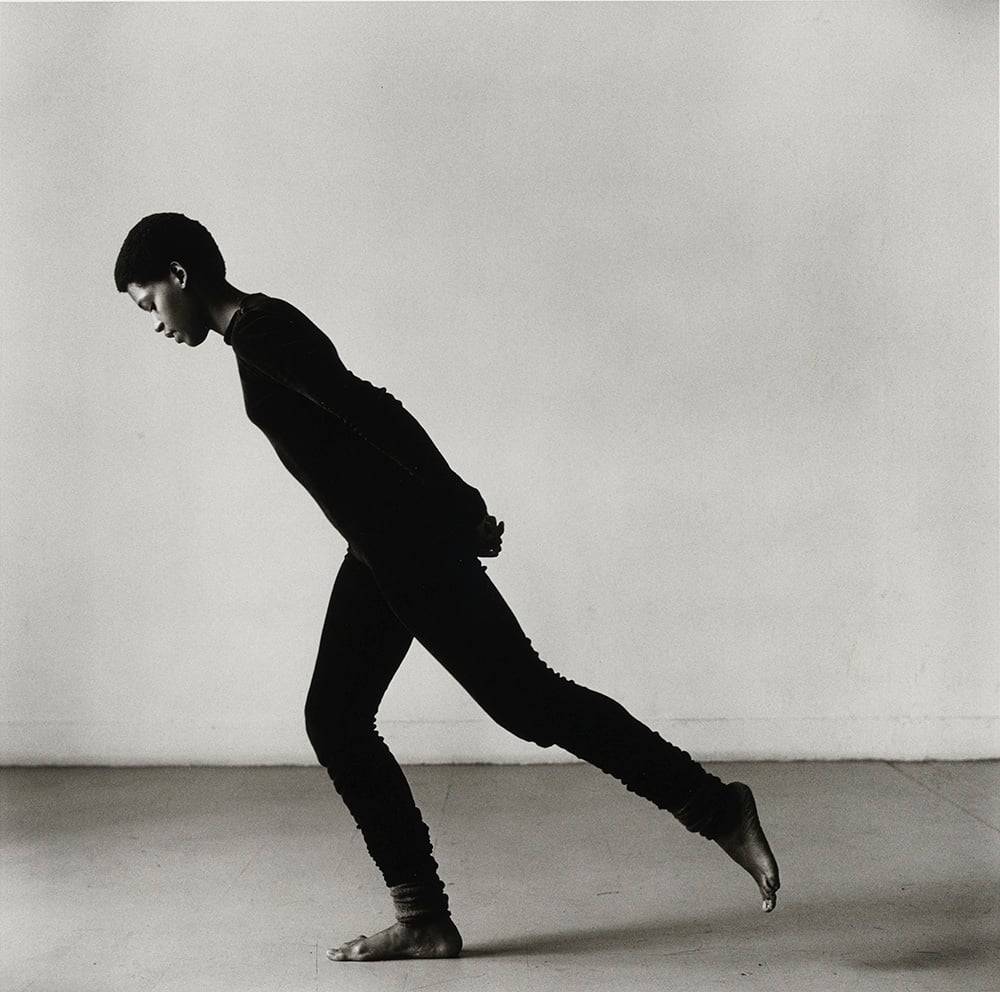

Peter Hujar, Sheryl Sutton (1977). © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and Fraenkel Gallery.

Peter Hujar, Boy on Raft (1978). © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and Fraenkel Gallery.

Peter Hujar, Dog, Westtown, New York (1978). © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and Fraenkel Gallery.

Peter Hujar, Steel Ruins (13) (1978). © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and Fraenkel Gallery.

Peter Hujar, Gary Schneider in Contortion (2) (1979). © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and Fraenkel Gallery.

Peter Hujar, Ethyl Eichelberger as Minnie the Maid (1981). © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and Fraenkel Gallery.

Peter Hujar, Gary Indiana Veiled (1981). © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and Fraenkel Gallery.

Peter Hujar, Greer Lankton (1983). © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and Fraenkel Gallery.